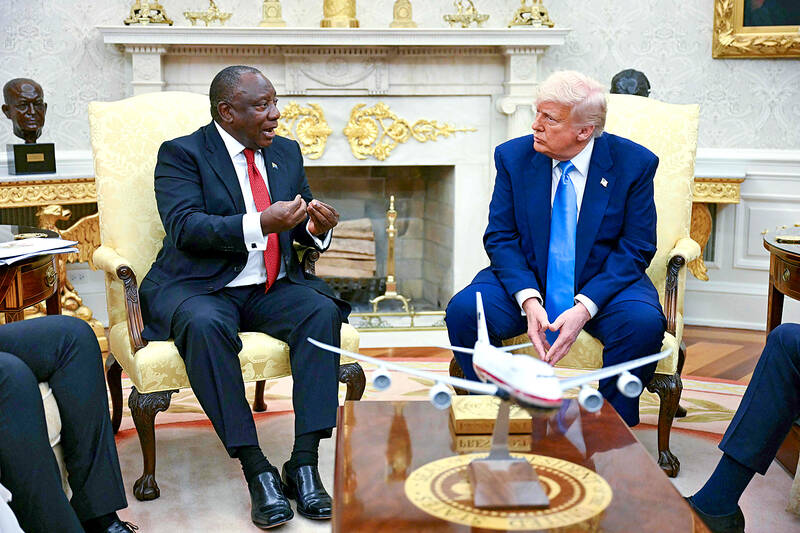

US President Donald Trump on Wednesday confronted South African President Cyril Ramaphosa with explosive false claims of white genocide and land seizures during a tense White House meeting that was reminiscent of his February ambush of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy.

South Africa has one of the highest murder rates in the world, but the overwhelming majority of victims are black.

Ramaphosa had hoped to use the meeting to reset his country’s relationship with the US, after Trump canceled much-needed aid to South Africa, offered refuge to white minority Afrikaners, expelled the country’s ambassador and criticized its genocide court case against Israel.

Photo: AFP

The South African president arrived prepared for an aggressive reception, bringing popular white South African golfers as part of his delegation and saying he wanted to discuss trade. The US is South Africa’s second-biggest trading partner, and the country is facing a 30 percent tariff under Trump’s currently suspended raft of import taxes.

However, in a carefully choreographed Oval Office onslaught, Trump pounced, moving quickly to a list of concerns about the treatment of white South Africans, which he punctuated by playing a video and leafing through a stack of printed news articles that he said proved his allegations.

With the lights turned down at Trump’s request, the video — played on a television that is not normally set up in the Oval Office — showed white crosses, which Trump asserted were the graves of white people, and opposition leaders making incendiary speeches. Trump suggested one of them, Julius Malema, should be arrested.

The video was made in September 2020 during a protest after two people were killed on their farm a week earlier. The crosses did not mark actual graves. An organizer of the protest told South Africa’s public broadcaster at the time that they represented farmers who had been killed over the years.

“People are fleeing South Africa for their own safety. Their land is being confiscated, and in many cases, they’re being killed,” Trump said, echoing a once-fringe conspiracy theory that has circulated in global far-right chat rooms for at least a decade with the vocal support of his ally, South African-born Elon Musk, who was in the Oval Office during the meeting.

South Africa, which endured centuries of draconian discrimination against black people during colonialism and apartheid before becoming a multiparty democracy in 1994 under Nelson Mandela, rejects Trump’s allegations.

Ramaphosa, sitting in a chair next to Trump and remaining poised, pushed back against his claims.

“If there was Afrikaner farmer genocide, I can bet you, these three gentlemen would not be here,” Ramaphosa said, referring to golfers Ernie Els and Retief Goosen and billionaire Johann Rupert, all white, who were present in the room.

That did not satisfy Trump.

“We have thousands of stories talking about it, and we have documentaries, we have news stories,” Trump said. “It has to be responded to.”

The extraordinary exchange, three months after Trump and Vice President JD Vance upbraided Zelenskiy inside the same Oval Office, could prompt foreign leaders to think twice about accepting Trump’s invitations and risk public embarrassment.

Unlike Zelenskiy, who sparred with Trump and ended up leaving early, the South African leader kept his calm, praising Trump’s decor and saying he looked forward to handing over the presidency of the G20 next year.

PARLIAMENT CHAOS: Police forcibly removed Brazilian Deputy Glauber Braga after he called the legislation part of a ‘coup offensive’ and occupied the speaker’s chair Brazil’s lower house of Congress early yesterday approved a bill that could slash former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s prison sentence for plotting a coup, after efforts by a lawmaker to disrupt the proceedings sparked chaos in parliament. Bolsonaro has been serving a 27-year term since last month after his conviction for a scheme to stop Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva from taking office after the 2022 election. Lawmakers had been discussing a bill that would significantly reduce sentences for several crimes, including attempting a coup d’etat — opening up the prospect that Bolsonaro, 70, could have his sentence cut to

A plan by Switzerland’s right-wing People’s Party to cap the population at 10 million has the backing of almost half the country, according to a poll before an expected vote next year. The party, which has long campaigned against immigration, argues that too-fast population growth is overwhelming housing, transport and public services. The level of support comes despite the government urging voters to reject it, warning that strict curbs would damage the economy and prosperity, as Swiss companies depend on foreign workers. The poll by newspaper group Tamedia/20 Minuten and released yesterday showed that 48 percent of the population plan to vote

A powerful magnitude 7.6 earthquake shook Japan’s northeast region late on Monday, prompting tsunami warnings and orders for residents to evacuate. A tsunami as high as three metres (10 feet) could hit Japan’s northeastern coast after an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 7.6 occurred offshore at 11:15 p.m. (1415 GMT), the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) said. Tsunami warnings were issued for the prefectures of Hokkaido, Aomori and Iwate, and a tsunami of 40cm had been observed at Aomori’s Mutsu Ogawara and Hokkaido’s Urakawa ports before midnight, JMA said. The epicentre of the quake was 80 km (50 miles) off the coast of

Brazilian Senator Flavio Bolsonaro on Friday said that his father, jailed former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, has chosen him to lead the country’s powerful conservative movement, shaking up next year’s election race. The 44-year-old senator said on social media that he will carry forward the political legacy that reshaped Brazilian politics. His announcement makes him an instant contender for the presidency. Jair Bolsonaro, 70, is unlikely to run after being sentenced to 27 years for plotting a coup and banned from public office. He is appealing and seeking a legislative pardon. The former president also faces serious health issues, including complications from a