Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro labeled them as terrorists on national television. They were plucked from pharmacies, apartment buildings and other locations, and thrown in prison for months. Many then endured severe beatings, food deprivation and other forms of torture. Virtually all developed stomach infections and lost weight. Three died.

More than 2,200 people were detained after Venezuela’s presidential election in July last year, when civil unrest broke out over Maduro’s claim to victory. With dissent firmly squelched, the government has slowly released nearly 1,900 of the mostly poor, politically unaffiliated 20-somethings.

Tearful reunions with family, some as recently as Friday last week. have brought them an immense sense of relief, but it vanishes with the realization that they are not truly free, neither physically nor mentally.

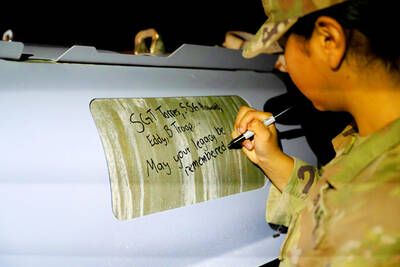

Photo: AP

Now at home, the former detainees, particularly those who participated in post-election rallies, must also cope with the disappointment that the votes they defended on the streets did not push Maduro out of office or produce the change they hoped for.

“You go home, see your loved ones and get drunk on happiness, but 24 to 48 hours later, reality hits you,” a man who was detained for more than five months said. “What is the reality? My fundamental rights were violated, and I am still at the mercy of the same government.”

The man and relatives of other former detainees told AP how the government’s repressive apparatus wrecked their lives after the July 28 election. Most spoke under the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals from the government, or its network of ruling-party loyalists who through physical force and control of state subsidies quash dissent.

Former detainees suffer insomnia, cannot be among crowds and tremble at the sight of a police officer. They have heart conditions not typical of young adults. They are worse off financially than before the election and cannot find work partly because their IDs were seized during their arrests.

They feel doubly insulted having to tap into the government’s precarious health, food and cash programs, but some see no other alternatives.

The families of the former detainees are indebted to loan sharks and acquaintances after spending hundreds of dollars in transportation, as well as meals, medicines, toiletries and other items not provided by the corrections system. Some mothers sob at night. Others silently carry the guilt that comes from having their children home again while other families are still making prison visits.

“The intimidation to which we are being subjected — the psychological damage that they are causing us — is the worst thing that can be done to a population … with a desire for freedom,” the mother of a former detainee said. “That is terrorism.”

Millions of Venezuelans expressed their desire for a change in government in the July election but electoral authorities loyal to the ruling party declared Maduro the winner hours after polls closed without providing detailed vote counts, unlike in previous elections.

Meanwhile, the main opposition coalition collected tally sheets from 85 percent of electronic voting machines showing that its candidate, Edmundo Gonzalez, won by a more than a two-to-one margin.

The dispute over the results sparked nationwide protests. The government responded with force, arresting more than 2,200 people, even if they had not participated in the demonstrations, and encouraging Venezuelans to report anyone they suspected of being a ruling-party adversary. More than 20 people were killed during the unrest.

Throughout Maduro’s presidency, state security forces have carried out mass arrests, but never like last year’s in terms of time span or primary demographic.

Previous protests were led primarily by young, college-educated, middle and upper-class Venezuelans of European descent who openly embraced the country’s political opposition. However, at the end of July, those on the streets were adolescents and young adults whose lives have been marked by poverty and letdowns from Maduro’s government.

“They were the children and grandchildren of the people who voted for Hugo Chavez,” said Oscar Murillo, head of the Venezuelan human rights group Provea, referring to Maduro’s predecessor. “They did not identify with the opposition. They came out in rejection of the poor management of the election results.”

However, in prison, part of the detainees were forced to wear uniforms in a shade of blue associated in Venezuela to an opposition party.

As time wore on inside overcrowded and sweltering cells, a few attempted suicide, some leaned into prayer and many were convinced they would all be freed by Jan. 11, the day after the presidential term, by law, begins in Venezuela. Those fixated on that deadline were banking on Gonzalez fulfilling his promise to return from exile and be sworn in as president.

Not only did Gonzalez not return, his son-in-law was also detained and remains in custody.

Since being released, former detainees and their loved ones now pray for health, work and a new president. However, they have sworn off politics.

“They instilled fear in political participation, which does a huge amount of damage to any society that wants progress and development in any country,” the former detainee said.

The Burmese junta has said that detained former leader Aung San Suu Kyi is “in good health,” a day after her son said he has received little information about the 80-year-old’s condition and fears she could die without him knowing. In an interview in Tokyo earlier this week, Kim Aris said he had not heard from his mother in years and believes she is being held incommunicado in the capital, Naypyidaw. Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was detained after a 2021 military coup that ousted her elected civilian government and sparked a civil war. She is serving a

REVENGE: Trump said he had the support of the Syrian government for the strikes, which took place in response to an Islamic State attack on US soldiers last week The US launched large-scale airstrikes on more than 70 targets across Syria, the Pentagon said on Friday, fulfilling US President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two US soldiers. “This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth wrote on social media. “Today, we hunted and we killed our enemies. Lots of them. And we will continue.” The US Central Command said that fighter jets, attack helicopters and artillery targeted ISIS infrastructure and weapon sites. “All terrorists who are evil enough to attack Americans are hereby warned

Seven wild Asiatic elephants were killed and a calf was injured when a high-speed passenger train collided with a herd crossing the tracks in India’s northeastern state of Assam early yesterday, local authorities said. The train driver spotted the herd of about 100 elephants and used the emergency brakes, but the train still hit some of the animals, Indian Railways spokesman Kapinjal Kishore Sharma told reporters. Five train coaches and the engine derailed following the impact, but there were no human casualties, Sharma said. Veterinarians carried out autopsies on the dead elephants, which were to be buried later in the day. The accident site

‘NO AMNESTY’: Tens of thousands of people joined the rally against a bill that would slash the former president’s prison term; President Lula has said he would veto the bill Tens of thousands of Brazilians on Sunday demonstrated against a bill that advanced in Congress this week that would reduce the time former president Jair Bolsonaro spends behind bars following his sentence of more than 27 years for attempting a coup. Protests took place in the capital, Brasilia, and in other major cities across the nation, including Sao Paulo, Florianopolis, Salvador and Recife. On Copacabana’s boardwalk in Rio de Janeiro, crowds composed of left-wing voters chanted “No amnesty” and “Out with Hugo Motta,” a reference to the speaker of the lower house, which approved the bill on Wednesday last week. It is