An elevator rattles down about 1km below ground in five minutes to reach Germany’s nuclear necropolis, a future repository set to entomb much of its radioactive waste.

At the bottom, a jeep ride takes helmet-clad engineers and visitors through an underground tunnel complex into a cold, cavernous hall with concrete-lined walls that rise up about 15m.

Atomic waste is to be encased in concrete at the subterranean Konrad repository “to prevent the radioactive substances from being released into the air,” project manager Ben Samwer said.

Photo: AFP

“The safety levels we want to achieve require a high degree of care,” Samwer told reporters during a visit to the multibillion-dollar project deep below the western city of Salzgitter.

The former iron ore mine is to become the final resting place for waste from the atomic power plants that Europe’s top economy has shuttered over the past few years.

Protests raged for decades in Germany over where to put its nuclear waste, leaving the Konrad site as the only approved location so far.

Photo: AFP

Konrad is meant to start operating in the early 2030s with space for more than 300,000m3 of material with low and intermediate levels of contamination.

However, more than a year since Germany’s last reactor was taken off the grid, under a nuclear phase-out decided following Japan’s 2011 Fukushima Dai-ichi disaster, the political issue is far from buried.

Besides the technical challenge, developers have battled protests and legal resistance which saw activists, unions and local representatives lodge a new challenge last month.

Photo: AFP

Environmental group Nabu said that the Konrad project was a “relic” that “does not meet the requirements for safe storage” and needs to be abandoned.

Below ground, the engineers are pushing on, confident they can clear the technical and political hurdles.

Germany has a “problem” with the leftovers from nuclear power projects, construction manager Christian Gosberg told reporters. “We cannot leave it for decades or centuries above ground where it is now.”

However, building a storage facility has proved “significantly more complex” than he expected when he joined the project six years ago, Gosberg said.

The expansion of the old mine comes with “special challenges,” he said, adding that much of the machinery used to excavate the tunnels has to be taken apart and reassembled underground.

In some cases, every piece of rebar has to be placed by workers and “individually screwed together,” Gosberg said. “The whole process is extremely complicated and of course takes a lot of time.”

Building delays have pushed the opening back and driven up the cost to about 5.5 billion euros (US$5.9 billion).

Meanwhile, the search for more sites goes on — Germany will need to find another two underground locations to accommodate yet more nuclear waste. For highly radioactive material, the difficult search for a safe place might last another half a century, the German government has said.

Mass protests around other earmarked locations through the 1980s and 1990s led to the abandonment of other sites, including at the nearby Asse mine and a facility by the town of Gorleben.

For Germany’s anti-nuclear movement, the closure of the last atomic reactor was a “huge success,” said activist Ursula Schoenberger, for whom the campaign has lasted about 40 years.

“At the same time, the problem of nuclear waste is still there and we have to deal with it,” Schoenberger said.

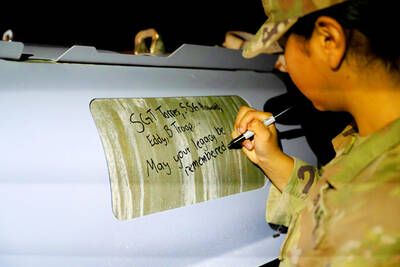

REVENGE: Trump said he had the support of the Syrian government for the strikes, which took place in response to an Islamic State attack on US soldiers last week The US launched large-scale airstrikes on more than 70 targets across Syria, the Pentagon said on Friday, fulfilling US President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two US soldiers. “This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth wrote on social media. “Today, we hunted and we killed our enemies. Lots of them. And we will continue.” The US Central Command said that fighter jets, attack helicopters and artillery targeted ISIS infrastructure and weapon sites. “All terrorists who are evil enough to attack Americans are hereby warned

Seven wild Asiatic elephants were killed and a calf was injured when a high-speed passenger train collided with a herd crossing the tracks in India’s northeastern state of Assam early yesterday, local authorities said. The train driver spotted the herd of about 100 elephants and used the emergency brakes, but the train still hit some of the animals, Indian Railways spokesman Kapinjal Kishore Sharma told reporters. Five train coaches and the engine derailed following the impact, but there were no human casualties, Sharma said. Veterinarians carried out autopsies on the dead elephants, which were to be buried later in the day. The accident site

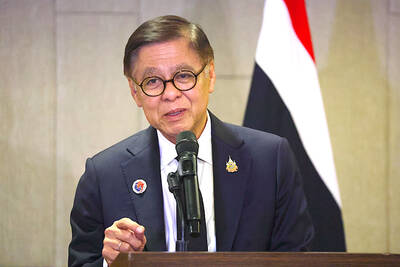

RUSHED: The US pushed for the October deal to be ready for a ceremony with Trump, but sometimes it takes time to create an agreement that can hold, a Thai official said Defense officials from Thailand and Cambodia are to meet tomorrow to discuss the possibility of resuming a ceasefire between the two countries, Thailand’s top diplomat said yesterday, as border fighting entered a third week. A ceasefire agreement in October was rushed to ensure it could be witnessed by US President Donald Trump and lacked sufficient details to ensure the deal to end the armed conflict would hold, Thai Minister of Foreign Affairs Sihasak Phuangketkeow said after an ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Kuala Lumpur. The two countries agreed to hold talks using their General Border Committee, an established bilateral mechanism, with Thailand

‘POLITICAL LOYALTY’: The move breaks with decades of precedent among US administrations, which have tended to leave career ambassadors in their posts US President Donald Trump’s administration has ordered dozens of US ambassadors to step down, people familiar with the matter said, a precedent-breaking recall that would leave embassies abroad without US Senate-confirmed leadership. The envoys, career diplomats who were almost all named to their jobs under former US president Joe Biden, were told over the phone in the past few days they needed to depart in the next few weeks, the people said. They would not be fired, but finding new roles would be a challenge given that many are far along in their careers and opportunities for senior diplomats can