At a packed festival in central Jakarta, hijab-clad sexagenarian singer Rien Djamain bursts into an upbeat track about nuclear destruction to a crowd of thousands, mostly young Indonesians.

Behind the lead woman of the all-female Nasida Ria band are her fellow musicians, dressed in silver and black sequined dresses, backing up her velvety vocals with bongos, violins, mandolins, bamboo flutes and tambourines.

“O cursed creator of the nuclear bomb, why do you invite the day of judgement?” she sang on the track Bom Nuklir.

Photo: Reuters

Young concertgoers swung from side-to-side during the macabre ditty, shouting “mother!” at their favorite band members.

Originally formed 47 years ago as a Koran recital group, the band numbers a dozen performers, fusing Arabic and traditional Indonesian dangdut music, which was once thought tacky and dated in cosmopolitan circles.

Their humorous Islamic pop tunes about serious themes, such as justice and human rights, have caught on with social media-obsessed young people looking for some levity in their playlists.

Riding the wave of Indonesia’s increasingly vibrant music scene, the band’s droll lyrics have gained them a certain notoriety. Their songs are laden with similes and metaphors, comparing womanizers to “seditious bats” or describing how “monkeys like to carry rifles, humans like to show nipples.”

Fathul Amin, 23, said he thinks the band is “more than just cool.”

“Why? Because all of the members are women who can play more than three musical instruments,” he said.

Screen grabs of Nasida Ria’s expressive words have been widely shared as memes, forging a connection between the band and the younger generation.

“That is how youths communicate nowadays, and that is OK. More importantly, it shows that our messages through the songs are well accepted,” Djamain said. “I am grateful that despite the mostly old members, Nasida Ria is still loved by the youths. That our music is still enjoyable to them.”

Music consumption in Indonesia is evolving, experts say, with listeners adding combinations of genres that include more traditional sounds — such as dangdut with Javanese lyrics or reggae-pop sung in eastern Indonesian dialects — to their Western favorites.

That growing trend has made Nasida Ria more relevant than ever, music journalist Shindu Alpito said.

“The younger generations tend to celebrate music with a sense of humor. They are attracted not only to the musical aesthetics but also musical comedy,” he said.

Dangdut music has been increasing in popularity, with acts playing at festivals across Indonesia, performing for young audiences alongside rock bands, in addition to gigs for their usual crowds in smaller villages.

“A lot of youths in ... Jakarta are re-embracing local music. Now, these types of music are what they call a guilty pleasure,” Alpito said. “Islamic songs are usually serious, with lyrics carefully quoting Islamic teachings. However, Nasida Ria have charmed broader society through a language style that is easy to understand and amusing.”

The group capitalized on the demand for entertainment while the world was stuck indoors and concert venues were closed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nasida Ria’s youngest member, 27-year-old Nazla Zain, attributes their success to modern technology allowing people from all backgrounds to be exposed to their music.

“We are keeping up with the trend by using YouTube and other music applications,” she said. “So now youths with mobile phones can listen to our songs. That might be a reason why they like us.”

They have seen their YouTube subscriber count surge sixfold since March 2020 to nearly 500,000. They also boast about 50,000 listeners every month on streaming platform Spotify, and have 38,000 followers on Instagram.

“They are so cool as they still perform at a not-so-young age,” said 32-year-old metal and punk fan Ricky Prasetyo. “No wonder many people call them the indie mothers.”

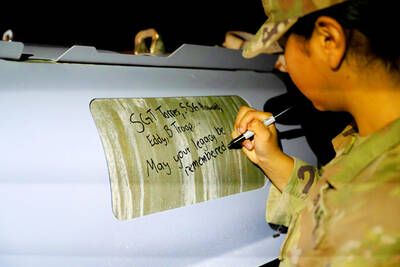

REVENGE: Trump said he had the support of the Syrian government for the strikes, which took place in response to an Islamic State attack on US soldiers last week The US launched large-scale airstrikes on more than 70 targets across Syria, the Pentagon said on Friday, fulfilling US President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two US soldiers. “This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth wrote on social media. “Today, we hunted and we killed our enemies. Lots of them. And we will continue.” The US Central Command said that fighter jets, attack helicopters and artillery targeted ISIS infrastructure and weapon sites. “All terrorists who are evil enough to attack Americans are hereby warned

Seven wild Asiatic elephants were killed and a calf was injured when a high-speed passenger train collided with a herd crossing the tracks in India’s northeastern state of Assam early yesterday, local authorities said. The train driver spotted the herd of about 100 elephants and used the emergency brakes, but the train still hit some of the animals, Indian Railways spokesman Kapinjal Kishore Sharma told reporters. Five train coaches and the engine derailed following the impact, but there were no human casualties, Sharma said. Veterinarians carried out autopsies on the dead elephants, which were to be buried later in the day. The accident site

‘POLITICAL LOYALTY’: The move breaks with decades of precedent among US administrations, which have tended to leave career ambassadors in their posts US President Donald Trump’s administration has ordered dozens of US ambassadors to step down, people familiar with the matter said, a precedent-breaking recall that would leave embassies abroad without US Senate-confirmed leadership. The envoys, career diplomats who were almost all named to their jobs under former US president Joe Biden, were told over the phone in the past few days they needed to depart in the next few weeks, the people said. They would not be fired, but finding new roles would be a challenge given that many are far along in their careers and opportunities for senior diplomats can

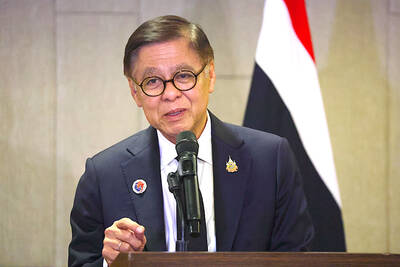

RUSHED: The US pushed for the October deal to be ready for a ceremony with Trump, but sometimes it takes time to create an agreement that can hold, a Thai official said Defense officials from Thailand and Cambodia are to meet tomorrow to discuss the possibility of resuming a ceasefire between the two countries, Thailand’s top diplomat said yesterday, as border fighting entered a third week. A ceasefire agreement in October was rushed to ensure it could be witnessed by US President Donald Trump and lacked sufficient details to ensure the deal to end the armed conflict would hold, Thai Minister of Foreign Affairs Sihasak Phuangketkeow said after an ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Kuala Lumpur. The two countries agreed to hold talks using their General Border Committee, an established bilateral mechanism, with Thailand