Preliminary results from two experiments suggest that something could be wrong with the basic way that physicists think the universe works, a prospect that has the field of particle physics both baffled and thrilled.

Tiny particles called muons are not quite doing what is expected of them in two long-running experiments in the US and Europe. The confounding results — if proven right — reveal major problems with the rulebook that physicists use to describe and understand how the universe works at the subatomic level.

“We think we might be swimming in a sea of background particles all the time that just haven’t been directly discovered,” Chris Polly, a scientist at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, or Fermilab, told a news conference.

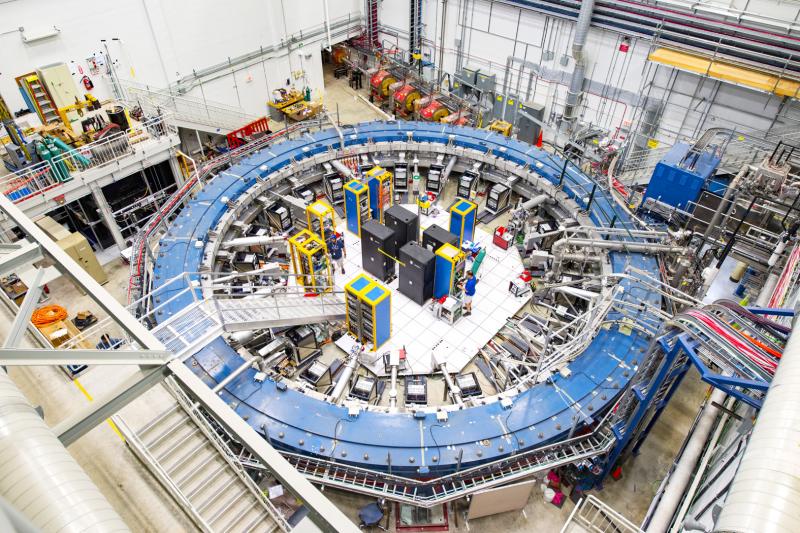

Photo: Fermilab via AP

“There might be monsters we haven’t yet imagined that are emerging from the vacuum interacting with our muons and this gives us a window into seeing them,” Polly added.

The rulebook, called the Standard Model, was developed about 50 years ago.

Experiments performed over decades affirmed over and again that its descriptions of the particles and the forces that make up and govern the universe were pretty much on the mark — until now.

On Wednesday, Fermilab announced the results of 8.2 billion races along a track outside Chicago that, while ho-hum to most people, have physicists astir: The muons’ magnetic fields do not seem to be what the Standard Model says they should be.

The point, Johns Hopkins University theoretical physicist David Kaplan said, is to pull apart particles and find out if there is “something funny going on” with both the particles and the seemingly empty space between them.

The muon is the heavier cousin to the electron that orbits an atom’s center.

“Since the very beginning it was making physicists scratch their heads,” said Graziano Venanzoni, who is one of the top scientists on the Fermilab experiment, called Muon g-2.

The experiment sends muons around a magnetized track that keeps the particles in existence long enough for researchers to get a closer look at them.

Preliminary results suggest that the magnetic “spin” of the muons is 0.1 percent off what the Standard Model predicts.

That may not sound like much, but to particle physicists, it is huge — more than enough to upend current understanding.

Researchers need another year or two to finish analyzing the results.

Separately, at the world’s largest atom smasher at the European Center for Nuclear Research’s Large Hadron Collider, physicists have been crashing protons against each other to see what happens afterward.

One experiment measures what happens when particles called beauty or bottom quarks collide.

The Standard Model predicts that these beauty quark crashes should result in equal numbers of electrons and muons, but that is not what happened.

Researchers pored over the data from a few thousand crashes and found a 15 percent difference, with significantly more electrons than muons, experiment researcher Sheldon Stone said.

Neither experiment is being called an official discovery yet because there is still a tiny chance that the results are statistical quirks.

If the results do hold, they would upend “every other calculation made” in the world of particle physics, Kaplan said.

“This is not a fudge factor. This is something wrong,” Kaplan said.

That something could be explained by a new particle or force.

Two medieval fortresses face each other across the Narva River separating Estonia from Russia on Europe’s eastern edge. Once a symbol of cooperation, the “Friendship Bridge” connecting the two snow-covered banks has been reinforced with rows of razor wire and “dragon’s teeth” anti-tank obstacles on the Estonian side. “The name is kind of ironic,” regional border chief Eerik Purgel said. Some fear the border town of more than 50,0000 people — a mixture of Estonians, Russians and people left stateless after the fall of the Soviet Union — could be Russian President Vladimir Putin’s next target. On the Estonian side of the bridge,

Jeremiah Kithinji had never touched a computer before he finished high school. A decade later, he is teaching robotics, and even took a team of rural Kenyans to the World Robotics Olympiad in Singapore. In a classroom in Laikipia County — a sparsely populated grasslands region of northern Kenya known for its rhinos and cheetahs — pupils are busy snapping together wheels, motors and sensors to assemble a robot. Guiding them is Kithinji, 27, who runs a string of robotics clubs in the area that have taken some of his pupils far beyond the rural landscapes outside. In November, he took a team

Civil society leaders and members of a left-wing coalition yesterday filed impeachment complaints against Philippine Vice President Sara Duterte, restarting a process sidelined by the Supreme Court last year. Both cases accuse Duterte of misusing public funds during her term as education secretary, while one revives allegations that she threatened to assassinate former ally Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. The filings come on the same day that a committee in the House of Representatives was to begin hearings into impeachment complaints against Marcos, accused of corruption tied to a spiraling scandal over bogus flood control projects. Under the constitution, an impeachment by the

Exiled Tibetans began a unique global election yesterday for a government representing a homeland many have never seen, as part of a democratic exercise voters say carries great weight. From red-robed Buddhist monks in the snowy Himalayas, to political exiles in megacities across South Asia, to refugees in Australia, Europe and North America, voting takes place in 27 countries — but not China. “Elections ... show that the struggle for Tibet’s freedom and independence continues from generation to generation,” said candidate Gyaltsen Chokye, 33, who is based in the Indian hill-town of Dharamsala, headquarters of the government-in-exile, the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA). It