At the “Genghis Security Academy,” which bills itself as China’s only dedicated bodyguard school, students learn that the threats to the country’s newly rich in the tech age are more likely to emerge from a hacker than a gunman.

Each day students in matching black business suits toil from dawn until midnight at the school in the eastern city of Tianjin, where digital defenses are given equal pegging to the traditional close-protection skill set of combat, weapons training and high-speed driving.

About 1,000 graduate each year, hoping to land jobs as guards to China’s burgeoning ranks of rich and famous, positions which can be worth up to US$70,000 — several times more than an annual office wage.

Photo: AFP

However, the school has said that it cannot meet demand as China’s rapid growth mints millionaires — 4.4 million according to a Credit Suisse report last year, more than in the US.

The course fees are up to US$3,000 a student; and while they had to cancel training between February and June because of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has not dampened demand.

Only the best make the cut, founder Chen Yongqing (陳永青) said, adding that his disciplinarian standards are stricter than in the army.

“I’m quick-tempered and very demanding,” the army veteran from China’s northern Inner Mongolia region told reporters.

“Only by being strict can we cultivate every good sword. If you don’t forge it well, it will break itself,” he said.

About half of the students are ex-military, Chen said.

They train in rows in a large, shabby sports hall, holding blue plastic guns ahead of them with a steady stare — before practicing hustling their clients safely into a black Audi with smashed windows.

Other sessions are held in a classroom or gym, where they box in matching red T-shirts.

Mobile phones are confiscated throughout, while meals are taken in silence in a large dining hall presided over by pictures of acclaimed graduates, who have protected everyone from China’s second-richest man, Jack Ma (馬雲), to visiting French presidents.

“We have been defining the standard of Chinese bodyguards,” instructor Ji Pengfei told reporters.

In one class, students in pairs worked through a scenario protecting a client from an intruder.

“Danger!” shouted Ji, prompting the guard to quickly throw their “boss” behind them and pull out a gun in the same move.

Those who failed to do it in two seconds were assigned 50 push-ups.

The guns at the Tianjin school are fake — China outlaws possession of firearms. For live firearms training, students are taken to Laos.

However, in a highly surveilled country with a low rate of street crime, the modern minder needs an up-to-date skill set, against state monitoring or professional hackers.

“Chinese bosses don’t need you to fight,” Chen told his students of a client base, which includes the country’s biggest real-estate and tech firms.

Repelling hacks on mobile phones, network security, spotting eavesdroppers and wiping data are all required tools in the bodyguard’s armory.

“What would you do if the boss wants to destroy a video file immediately?” Chen asked a class.

Even so, old-school threats still exist in China — earlier this year billionaire He Xiangjian (何享健), founder of Midea and one of the country’s richest men, was kidnapped at his home.

According to Chinese media, He’s son escaped by jumping into a river and was able to call the police, who said they arrested five suspects at the scene.

Student Zhu Peipei, a 33-year-old army veteran from northern Shanxi Province, hoped that becoming a bodyguard could offset his lack of professional skills or academic qualifications.

“And of course, it’s cool,” he added.

However, the alumni of the Genghis Academy also provide humdrum services, like accompanying children of the rich and famous to school — for a fee of 180,000 yuan (US$26,592) a year.

That in itself is far more than the base salary in private companies of about 53,000 yuan.

Students must also navigate the quirks of their wealthy clients, Ji said.

Some only trust bodyguards whose Chinese zodiac sign matches theirs, he said — while one, from a Fortune 500 company, only wanted to hire from his hometown.

Another demanded a prospective bodyguard tell him what books he liked to read — he was hired after saying he liked military novels.

The best can command as much as 500,000 yuan a year inside China, but some set their sights on a posting overseas, potentially working with foreign clients.

“I want to work in the Philippines or Myanmar,” one student said, requesting anonymity. “Then I can carry a gun ... it will be more challenging and I can earn more.”

Auschwitz survivor Eva Schloss, the stepsister of teenage diarist Anne Frank and a tireless educator about the horrors of the Holocaust, has died. She was 96. The Anne Frank Trust UK, of which Schloss was honorary president, said she died on Saturday in London, where she lived. Britain’s King Charles III said he was “privileged and proud” to have known Schloss, who cofounded the charitable trust to help young people challenge prejudice. “The horrors that she endured as a young woman are impossible to comprehend and yet she devoted the rest of her life to overcoming hatred and prejudice, promoting kindness, courage, understanding

US President Donald Trump on Friday said Washington was “locked and loaded” to respond if Iran killed protesters, prompting Tehran to warn that intervention would destabilize the region. Protesters and security forces on Thursday clashed in several Iranian cities, with six people reported killed, the first deaths since the unrest escalated. Shopkeepers in Tehran on Sunday last week went on strike over high prices and economic stagnation, actions that have since spread into a protest movement that has swept into other parts of the country. If Iran “violently kills peaceful protesters, which is their custom, the United States of America will come to

‘DISRESPECTFUL’: Katie Miller, the wife of Trump’s most influential adviser, drew ire by posting an image of Greenland in the colors of the US flag, captioning it ‘SOON’ US President Donald Trump on Sunday doubled down on his claim that Greenland should become part of the US, despite calls by the Danish prime minister to stop “threatening” the territory. Washington’s military intervention in Venezuela has reignited fears for Greenland, which Trump has repeatedly said he wants to annex, given its strategic location in the arctic. While aboard Air Force One en route to Washington, Trump reiterated the goal. “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” he said in response to a reporter’s question. “We’ll worry about Greenland in

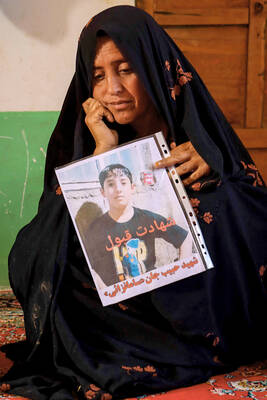

PERILOUS JOURNEY: Over just a matter of days last month, about 1,600 Afghans who were at risk of perishing due to the cold weather were rescued in the mountains Habibullah set off from his home in western Afghanistan determined to find work in Iran, only for the 15-year-old to freeze to death while walking across the mountainous frontier. “He was forced to go, to bring food for the family,” his mother, Mah Jan, said at her mud home in Ghunjan village. “We have no food to eat, we have no clothes to wear. The house in which I live has no electricity, no water. I have no proper window, nothing to burn for heating,” she added, clutching a photograph of her son. Habibullah was one of at least 18 migrants who died