They roamed the savannahs and open plains for thousands of years, but the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of southern Africa's San tribes is slowly being squeezed towards extinction.

After clashing at the start of the last century with German settlers in modern-day Namibia and then being exploited by South Africa's apartheid regime in the 1980s, the San, also known as Bushmen, are now threatened by the 21st century curses of unemployment, poverty, alcohol abuse and HIV-AIDS.

While the plight of the San in Botswana made headlines in recent months when authorities illegally evicted tribes from the Kalahari, their kinsmen in Namibia and South Africa have fared little better in protecting their traditional habitat.

A glimmer of hope lies in tourism as operators discover this remote part of Namibia where the likes of Gcao Nari, a grandmother of the Juhoansi San tribe, showcase the ancient art of threading ostrich shell beads.

But in a sign of the times, the beads that Nari painstakingly needles under the fierce sun are imported from neighboring South Africa since there are no ostriches left in the area of the remote northeastern Otjozondjupa region.

Nari speaks softly to her granddaughter in the ancient San tongue, with complicated clicks rolling from her lips as she enthuses about tentative plans to re-introduce game to the area as a source of food and income for a people with unparalleled hunting abilities.

"Then my grandchildren can be taught to hunt again," she says.

About 30,000 San remain in Namibia, with the Haikom and Juhoansi the largest groups.

Their numbers dived from the start of the last century when then colonial ruler Germany allowed growing numbers of white settlers to shoot Bushmen and encroach on their traditional hunting grounds.

South Africa took over the territory's administration during the World War I until Namibia's independence in 1990, which followed a protracted liberation war.

Nari remembers the 1970s when the South African military came to enlist the help of the San in return for certain favors.

"They used my husband and other men of our village as trackers along the border with Angola to fight freedom fighters," she says through an interpreter. "The military drilled boreholes for us and taught our children, their doctors in uniform gave us medical treatment and my husband earned a salary."

Other San like the Khwe and Vasekele originated in Angola, were employed by Portuguese colonial military forces during that country's liberation struggle, but fled to Namibia after Angolan independence in 1975.

They were wedged between two warring factions.

The South African military gave them shelter in then South West Africa; the men became trackers and soldiers in a special "Bushman Battalion" against the Peoples' Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN).

In 1990, some 1,000 San soldiers and their families took up an offer from the Pretoria government to settle at Schmidtsdrift, near Kimberley in South Africa's arid Northern Cape Province, fearing reprisals from the new Namibian government if they stayed.

The 5,000-strong !Xu -- an exclamation point precedes the word to represent the distinctive click sounds in their language -- and Khwe communities left in the Northern Cape today have been reduced to relying on government pensions and food handouts.

"I feel caged," says 84-year-old Monto Masako in his sparsely furnished three-room home at Platfontein, as he dreamily recalls his childhood. "My father taught me to hunt with a bow and arrow. We slept in the veld -- it was so free. But that has all been taken away, we can never go back."

The Burmese junta has said that detained former leader Aung San Suu Kyi is “in good health,” a day after her son said he has received little information about the 80-year-old’s condition and fears she could die without him knowing. In an interview in Tokyo earlier this week, Kim Aris said he had not heard from his mother in years and believes she is being held incommunicado in the capital, Naypyidaw. Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was detained after a 2021 military coup that ousted her elected civilian government and sparked a civil war. She is serving a

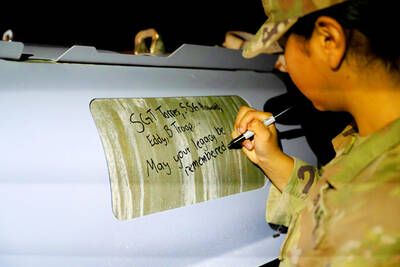

REVENGE: Trump said he had the support of the Syrian government for the strikes, which took place in response to an Islamic State attack on US soldiers last week The US launched large-scale airstrikes on more than 70 targets across Syria, the Pentagon said on Friday, fulfilling US President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two US soldiers. “This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth wrote on social media. “Today, we hunted and we killed our enemies. Lots of them. And we will continue.” The US Central Command said that fighter jets, attack helicopters and artillery targeted ISIS infrastructure and weapon sites. “All terrorists who are evil enough to attack Americans are hereby warned

Seven wild Asiatic elephants were killed and a calf was injured when a high-speed passenger train collided with a herd crossing the tracks in India’s northeastern state of Assam early yesterday, local authorities said. The train driver spotted the herd of about 100 elephants and used the emergency brakes, but the train still hit some of the animals, Indian Railways spokesman Kapinjal Kishore Sharma told reporters. Five train coaches and the engine derailed following the impact, but there were no human casualties, Sharma said. Veterinarians carried out autopsies on the dead elephants, which were to be buried later in the day. The accident site

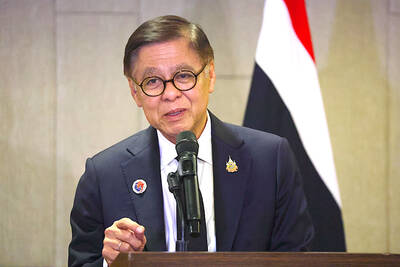

RUSHED: The US pushed for the October deal to be ready for a ceremony with Trump, but sometimes it takes time to create an agreement that can hold, a Thai official said Defense officials from Thailand and Cambodia are to meet tomorrow to discuss the possibility of resuming a ceasefire between the two countries, Thailand’s top diplomat said yesterday, as border fighting entered a third week. A ceasefire agreement in October was rushed to ensure it could be witnessed by US President Donald Trump and lacked sufficient details to ensure the deal to end the armed conflict would hold, Thai Minister of Foreign Affairs Sihasak Phuangketkeow said after an ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Kuala Lumpur. The two countries agreed to hold talks using their General Border Committee, an established bilateral mechanism, with Thailand