Chinese Practice

自食惡果

(zi4 shi2 e4 guo3)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

to eat one’s own bitter fruit

《坎特伯里故事集》是傑弗里‧喬叟在西元一三八七年至一四○○年之間以中古英語寫成的作品。該書是一故事集,說一群朝聖者從倫敦到坎特伯里朝聖,途中輪流講故事,看誰講得最好。其中〈教士的故事〉,是一段說明拋棄世俗的莊嚴、正式的講道,詳細說明高貴的行為──其中包括贖罪、悔改、懺悔、施捨、苦修和禁食,以及「七大罪」──驕傲、嫉妒、憤怒、懶惰、貪婪、貪食和淫亂。教士在談到「憤怒」時,他轉而談及「詛咒」,說這是來自「憤怒的心」。

在中世紀的英格蘭,「cursing」(詛咒)真的會產生魔法的效果,而不僅是現今所意指的「粗話」。詛咒被視為是一種罪,對詛咒的人和被詛咒的人都有害。正如教士所說:

「Malisoun generally may be seyd every maner power of harm. Swich cursynge bireveth man fro the regne of God, as seith Seint Paul. And oft tyme swiche cursynge wrongfully retorneth agayn to hym that curseth, as a byrd that retorneth agayn to his owene nest」(詛咒可能有各種害處。正如聖保羅告訴我們的,咒詛會使人遠離上帝的國度。詛咒常會回到發出詛咒的人,就像一隻鳥會回到牠的巢)。

教士說詛咒會回到詛咒者,「就像一隻鳥回到牠的巢」(like a bird returning to its nest)這個比喻,及其衍伸義──所做的任何壞事都會在日後回過頭來到做壞事的人身上,在一三九○年喬叟動念要寫此書時,已是眾所周知的概念。兩世紀之後,一五九二年的戲劇《The Lamentable and True Tragedie of Master Arden Of Feversham in Kent: Who Was Most Wickedlye Murdered, By the Meanes of His Disloyall and Wanton Wyfe》(肯特郡費弗舍姆阿登少爺哀傷的真實悲劇:被他不忠、淫蕩的夫人極其惡毒地謀殺)(此劇被認為是莎士比亞所作),重新審視了詛咒回到發出詛咒者的概念,雖然用了不同的比喻:

「因為詛咒就像直直向上射出的箭,

箭會往下掉,射到這射手的頭。」

到了十九世紀,英國浪漫主義詩人羅伯‧邵塞(一七七四~一八四三年)一八一○年的詩《克哈馬的詛咒》,其扉頁題詞為「Curses are like young chicken: they always come home to roost」(詛咒就像小雞一樣:牠們總是回到雞棚休息)。

此處是用雞回雞棚來比喻詛咒,而不是用一般的鳥類來比喻,但其概念是相同的:所說出的咒語、所幹的壞事,會在未來某個時間點回來傷害你。

完整的說法「curses are like chickens; they always come home to roost」現今在北美仍很常見,另一略為縮短的版本「chickens always come home to roost」也廣為使用。簡短版裡沒有「curse」一字,因此「chicken」指任何將來會以某種方式反撲的壞事。

中文裡類似的成語是「自食惡果」,字面意為「吃自己的苦果」,意思是遭受自己行為的後果。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

我一直懶得動筆,現在假期要結束了才發現作業太多寫不完,真是自食惡果。

(I’ve been dragging my feet. Now the vacation is almost over, and I’ve realized how much work I have to do: I will never get it done. I only have myself to blame.)

英文練習

chickens always come home to roost

Geoffrey Chaucer’s Middle English work The Canterbury Tales, written between 1387 and 1400, is a set of stories related by a group of pilgrims, travelling from London to Canterbury, as part of a story-telling contest. One of these, the Parson’s Tale, is a solemn, formal sermon on the renunciation of the mundane world, spelling out the noble ways — among them penitence, contrition, confession, giving alms, doing penance and fasting — as well as the Seven Deadly Sins of pride, envy, anger, sloth, avarice, gluttony, and lechery. In his discussion on anger, he turns to the matter of “cursing,” saying how this comes from an “angry heart.”

In the Middle Ages in England, cursing had consequences. It was not just seen as rude or uncouth, as it is today: it was seen as a sin, and harmful to both the person giving the curse and the person receiving it. As the parson says, “Malisoun generally may be seyd every maner power of harm. Swich cursynge bireveth man fro the regne of God, as seith Seint Paul. And oft tyme swiche cursynge wrongfully retorneth agayn to hym that curseth, as a byrd that retorneth agayn to his owene nest. (Cursing may be said to have all manner of harm. Such cursing takes man away from the Kingdom of God, as St Paul tells us. And cursing often comes back to the curser, like a bird returning to its nest.”

The parson’s reference to the curse returning to the curser, “like a bird returning to its nest,” and by extension any bad deed coming back to haunt a person later on in life, was a known concept when Chaucer committed the idea to writing in 1390. Two centuries later, in the 1592 play The Lamentable and True Tragedie Of Master Arden Of Feversham In Kent: Who Was Most Wickedlye Murdered, By The Meanes Of His Disloyall And Wanton Wyfe (thought to have been written by William Shakespeare), the idea of curses returning to harm the curser is revisited, albeit with a different metaphor:

“For curses are like arrowes [arrows] shot upright,

Which falling downe light on [hit] the suters [shooter’s] head.”

In the 19th century now, in 1810, the title page motto for English Romantic poet Robert Southey’s (1774-1843) poem The Curse of Kehama was “Curses are like young chicken: they always come home to roost.”

Here we have the curses being compared to chickens specifically, and not just birds in general, coming home to roost, but the idea is the same: Curses said, or ill deeds committed, now will come back to harm you in an unspecified future.

The full phrase “curses are like chickens; they always come home to roost” is still common in North America, and another, slightly truncated, version, is used more widely: “chickens always come home to roost.” In this case, with no “curse” mentioned specifically, the “chickens” can mean any bad deeds that will rebound on you somehow.

In Chinese, a similar idiom is 自食惡果, literally “to eat one’s own bitter fruit,” meaning to suffer the consequences of your own actions.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

After years of suppression, the local people rose up against the dictator. He is finally seeing the chickens come home to roost.

(經過多年的壓迫,當地人民終於起義對抗獨裁者,他總算自食惡果。)

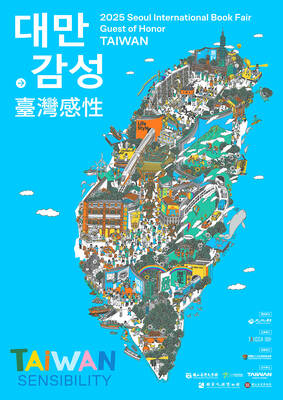

The 2025 Seoul International Book Fair was held from June 18 to 22 at the COEX Convention & Exhibition Center in Seoul, South Korea. This year, participants from 17 countries attended, with over 530 publishing houses and related organizations taking part. For the first time, Taiwan participated in the book fair as the Guest of Honor, bringing together more than 85 publishers and presenting a curated selection of 550 titles. A delegation of 23 Taiwanese creatives traveled to Seoul to attend the event, including 13 literary authors, six illustrators, and four comic book artists, among which were a film director, an

In late 2024, the suicide of acclaimed Taiwanese author Chiung Yao at 86 sparked a societal debate. She expressed her desire to avoid the difficult aging process and sought to govern her own death rather than leave it to fate. Her statements propelled the issue of “euthanasia” back into the public arena, posing the question of whether Taiwan should legalize euthanasia to grant patients and the elderly the right to die with dignity. Euthanasia, the intentional ending of a life to relieve suffering, is legal for humans in countries like the Netherlands and Belgium but remains prohibited in Taiwan.

A: Wow, the 36th Golden Melody Awards ceremony is set for this weekend. B: I like all the nominees for Best Mandarin Album: Incomplete Rescue Manual by various artists, Outcomes by J.Sheon, Invisible Color by Terence Lam, The Dreamer by Khalil Fong, Haosheng Haochi by Trout Fresh and Ordeal by Pearls by Waa Wei. A: Despite struggling with serious illness, Fong managed to finish his last album before he died. B: With his hit Twenty Three, he is also nominated for Best Song, Lyricist and Composer, and will receive a Special Jury Award for his album. A: And

A: The Golden Melody Awards’ Lifetime Achievement Award will go to both musician Bruce Wong and late singer Jeff Ma. B: Some superstars also won this honor in the past, such as late singer Teresa Teng. A: Speaking of Teresa, have you heard that an unreleased Japanese song of hers was found recently? B: Really? Will the song be released? A: Yes, her track Love Song in the Night Fog is set to be released this month, marking the 30th anniversary of the legendary singer’s death. A: 本屆金曲獎特別貢獻獎頒給樂手翁孝良、已故歌手馬兆駿。 B: 以往有不少超級巨星,像是已故歌后鄧麗君也曾獲此殊榮唷。 A: 說到鄧麗君,你有聽說她生前未發布的日文歌曲被發現了嗎? B: 真的嗎?新歌會公開嗎? A: 這首歌《情歌最愛夜霧時》預計本月發布,正好紀念傳奇歌后去世30週年! (By Eddy