Chinese practice

治絲益棼

(zhi4 si1 yi4 fen2)

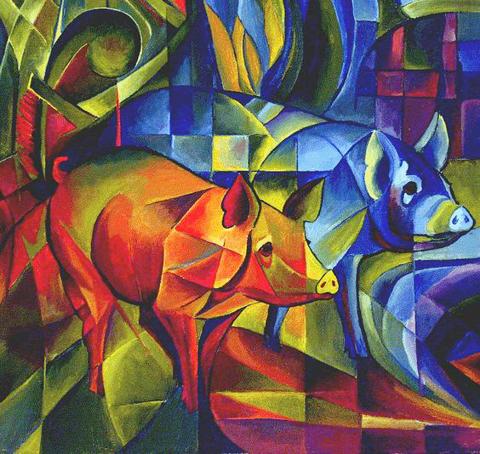

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

straighten silk, but tangle it up

成語「治絲益棼」,亦作「治絲而棼」,其出處與八月二十日「活用成語」介紹的「玩火自焚」相同,源於《春秋左傳》的同一段。《春秋》記載,魯隱公四年(公元前七一九年),衛國公子州吁計畫攻打鄭國。《左傳》註解說,魯國大夫眾仲認為州吁的計畫會徹底失敗──眾仲說道:「臣聞以德和民,不聞以亂,以亂,猶治絲而棼之也」(我只聽過統治者以仁慈和美德贏得人心,但從未聽說可以用混亂和失序來贏得人心的。若是利用混亂和失序,就像是要理順絲線卻不先去找頭緒,結果就越理越亂。)

事實證明,眾仲是對的:後來州吁果然陷入了困境,在一年之內就被其人民殺了。

在現代漢語中,「治絲益棼」是用來說某人把事情弄得一團糟,若繼續下去,只會讓情況更糟。

在英文裡,若要說某人把事情搞得亂七八糟,可以用一句有趣的短語來說──「to make a pig’s ear of something」(把某事弄成豬耳朵,意為把事情搞砸)。很湊巧,這句話的起源也跟絲線有關。

「make a pig’s ear of」這句話第一次出現,是在一九五○年版的美國大眾家庭雜誌《讀者文摘》──其中有一句話:「If you make a pig’s ear of the first one, you can try the other one.」(如果你把第一個弄成了豬耳朵,你可以試試下一個)。這句話的靈感卻是來自一五七九年的一本書──《The Ephemerides of Phialo, Divided into Three Books》(菲蘿的日記,共三冊),為英國教士史蒂芬‧戈森所著,他用一句很有創意的短語「Seekinge too make a silke purse of a Sowes eare」(試圖用豬耳朵來做絲綢錢包),來指嘗試去做一些注定會失敗的事。「sow」字的意思是成年的母豬。

另一個可表達把事情弄糟的說法,是一個簡單的動詞「botch」,及其衍生形容詞,例如「to botch up」某事,或做一件「botched job」。這兩者都意指把事情做得很糟糕,結果不盡如人意。

「botch」一詞來自十四世紀晚期的字「bocchen」,原指「修復」,但後來,到了一五二○年代,就意指「拙劣地修理」或「被笨拙的手法所糟蹋」。

所以我們可以說,差不多三千年前,在現今中國一個名叫州吁的人,密謀鞏固他對衛國非法獲得的統治權,但卻「thoroughly botched it up」(徹底搞砸了),且「made a real pig’s ear of the whole affair」(徹底毀掉了整件事)。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

兩國的恩怨糾葛由來已久,此時貿然採用強硬手段,非但無助於解決問題,反而可能治絲益棼。

(To now employ such hardline measures, given the longstanding enmity and tensions between these two countries, will not only fail to resolve the situation, it will actually make matters worse.)

輔導室應該協助同學冷靜處理感情難題,以免治絲益棼,又生風波。

(The Counselors’ Office should help students deal with their emotional issues, so that they can keep things under control and the situation does not deteriorate further.)

英文練習

make a pig’s ear out of something;

to botch something up

The idiom 治絲益棼, also written 治絲而棼, derives from the same passage of the chun qiu zuo zhuan (Commentary of Zuo of the Spring and Autumn Annals) that Using Idioms looked at on Aug. 20, discussing 玩火自焚 (if you play with fire, you’ll get your fingers burned). The chun qiu entry for the fourth year of Duke Yin (719BC) of Lu tells of how Zhou Xu of Wei plans to attack Zheng, and the attendant zuo zhuan commentary relates how the duke’s senior official Zhong Zhong suspects that Zhou Xu’s plan can only end in disaster. The relevant section has Zhong Zhong say 臣聞以德和民,不聞以亂,以亂,猶治絲而棼之也 (I have heard of winning over the people through virtue, but never through chaos and disorder; to attempt this through chaos and disorder is like trying to straighten out silk threads but only getting them more tangled).

As it turned out, he was right: Zhou Xu got himself in a tangle, and was put to death by his own people within the year.

In modern Chinese, 治絲益棼 is used to say that somebody is making a mess of things, and will only make matters worse by continuing what they are doing.

In English, when we want to say somebody is making a mess of things, we have the curious phrase “to make a pig’s ear of something.” As it happens, the origins of this phrase also have something to do with silk.

The phrase “make a pig’s ear of” something apparently first appears in a 1950 edition of the American general-interest family magazine Reader’s Digest, in the sentence “If you make a pig’s ear of the first one, you can try the other one.” The inspiration for this stretches back much further, however, to a 1579 book, The Ephemerides of Phialo, Divided into Three Books, by the English clergyman Stephen Gosson, where he uses the inventive phrase “Seekinge too make a silke purse of a Sowes eare” (seeking to make a silk purse from a pig’s ear) to mean attempting to do something that is doomed to failure. A sow is an adult, female pig.

Another word, this time a simple verb and its derivative adjective, is “botch,” as in “to botch up” something or to do a “botched job.” These both mean to do a task badly, with unsatisfactory results.

The word “botch” comes from the late 14th century word bocchen, originally meaning “to repair” but later, by the 1520s, to mean “repair clumsily,” or “to spoil through unskillful work.”

Almost three millennia ago, in other words, a man in what is now China named Zhou Xu conspired to consolidate his rule, illegitimately gained, of the state of Wei, but thoroughly botched it up, and made a real pig’s ear of the whole affair.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

Well, you’ve made a real pig’s ear of that, haven’t you? I think you should start again.

(嗯,你真的是把它給搞砸了,難道不是嗎?我覺得你應該再重頭來過。)

Think carefully about how you’re going to do this. It’s important. You don’t want to botch it up.

(你要好好想想該怎麼進行這件事,這很重要。我們不希望把事情搞砸。)

A: Wow, Les Miserables Staged Concert Spectacular is visiting Taiwan for the first time. B: Isn’t Les Miserables often praised as one of the world’s four greatest musicals? A: Yup. Its concert is touring Taipei from tonight to July 6, and Kaohsiung between July 10 and 27. B: The English version of the French musical, based on writer Victor Hugo’s masterpiece, has been a huge success throughout the four decades since its debut in 1985. A: The musical has never toured Taiwan, but going to the concert sounds like fun, too. A: 哇,音樂劇《悲慘世界》紀念版音樂會首度來台巡演! B: 《悲慘世界》……它不是常被譽為全球四大名劇之一嗎? A: 對啊音樂會將從今晚到7月6日在台北演出,從7月10日到27日在高雄演出。 B: 這部法文音樂劇的英文版,改編自維克多雨果的同名小說,自1985年首演以來,在過去40年造成轟動。 A:

Some 400 kilometers above the Earth’s surface, the “International Space Station” (ISS) operates as both a home and office for astronauts living and working in space. Astronauts typically stay aboard the station for up to six months and engage in groundbreaking research projects in various fields, such as biology, physics and astronomy. These projects help scientists understand life in space and contribute to advancements that benefit people on Earth. The ISS has experienced significant growth since construction began in 1998. The station’s design and assembly represent an extraordinary international collaboration among Canada, the European Union, Japan, Russia and the United States.

A: While hit musical Les Miserables’ concert tour kicks off, South Korean drama Squid Game 3 will be back at the end of this month. B: New Taiwanese dramas The World Between Us 2 and Zero Day Attack have also gained attention. A: I heard that Zero Day Attack is a story about the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Liberation Army trying to attack Taiwan by force. B: The drama’s subject is so sensitive that it has sparked a lot of controversy in society. A: I just hope that such a horrible story will never happen in

Continued from yesterday(延續自昨日) https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/lang Living on the ISS is challenging due to the absence of gravity. Astronauts must strap themselves into sleeping bags to prevent floating away while they sleep. They also spend about two hours exercising daily using specialized equipment. Despite this, microgravity can cause muscle loss, bone density reduction and cardiovascular changes. As a result, astronauts require extensive rehabilitation upon their return to Earth. In spite of these difficulties, astronauts often describe their experience on the ISS as life-changing. One of the most awe-inspiring aspects of living aboard the space station is the unparalleled view of Earth. Traveling at