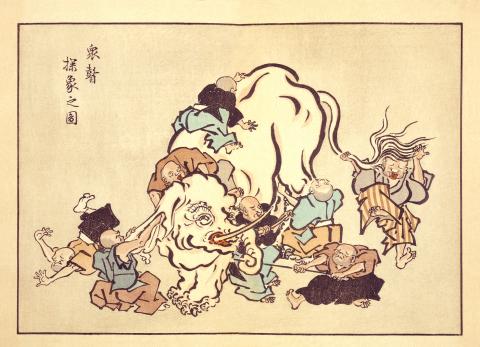

Chinese practice

瞎子摸象

blind men feeling an elephant

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

(xia1 zi5 mo1 xiang4)

人對事件、事物或過程的理解方式有個特性,就是我們傾向把所能感知到、對我們有利的資訊,想像成是完整的,並據此形成自己的觀點,卻不知道(或不願去想像)這些訊息可能是不完整的。這種傾向在一個古老的寓言故事中完全體現了出來,這寓言起源於印度,並在佛教、印度教和耆那教經籍中以不同的形式出現,第一個版本可追溯到佛教典籍《自說經》,年代可追溯至公元前一千年。這個故事是圍繞著一群盲人展開,他們想知道大象是長什麼樣子,而各自觸摸了大象身體的一部分,結果每個人對大象長什麼樣子的描述,卻是各自表述、大相逕庭。

例如,在據信編纂於西元一○○至二二○年間的《大般涅槃經》(英文本譯者為山本晃紹)中,第三十九章〈獅子吼菩薩品〉對於「佛性」的討論,提到了一個故事──國王要求他一位大臣在一群盲人面前展示一頭大象,然後問他們大象的模樣為何。

「其觸牙者即言象形如蘆菔根。(摸到象牙的人說:「大象就像是蘿蔔。」)

其觸耳者言象如箕。(摸到象耳朵的人說:「大象就像一個揚穀箕。」)

其觸鼻者言象如杵。(摸到象鼻的人說:「大象就像一根杵。」)

其觸腳者言象如木臼。(摸到象腳的人說:「大象就像一個木製的研磨臼。」)

其觸脊者言象如床。(摸到象的背脊的人說:「大象就像一張床。」)

其觸腹者言象如甕。(摸到象的肚子的人說:「大象就像一個甕。」)

其觸尾者言象如繩。(摸到象尾巴的人說:「大象就像一條繩子。」)」

於是國王說道:

「所有這些盲人都無法辨認大象長什麼樣子,但又不是說他們都沒做出任何對大象的描述。所有這些描述都是大象的一個面向,若沒有這些部分,就不成其為大象。」

這部經所討論的,是「佛性」的存在。「the blind men and the elephant」(盲人與大象)的寓言如今已有更廣泛的用法,表示知識是偏頗的──即便這些知識是靠親身經驗所獲得的──因此可能會造成很大的誤導。

這個寓言的簡單性和巧思,讓世界各地不同文化和國家的人都受到了啟發;在中文裡,它體現在「瞎子摸象」這個成語裡。 (台北時報林俐凱譯)

你做出評斷之前要有通盤的了解,不要只是根據個人瞎子摸象的侷限視野和理解。

(You should have understood it completely before making your assessment, not just got a partial understanding and insight like the proverbial blind man feeling the elephant.)

投資者在這個新興市場其實就如瞎子摸象,還在摸索它的反應和運作型態。

(Investors in this emerging market are like the blind men feeling the elephant; they’re still exploring how it reacts and operates.)

英文練習

the parable of the blind men and the elephant

A feature of the way people tend to understand an event, an object or a process is that we take all of the information our perception avails us of and, imagining it to be complete, form an opinion based upon that, unaware (or unwilling to conceive) that this information may well be partial. This tendency is perfectly captured in a parable of considerable antiquity, originating in the Indian subcontinent and appearing, in one form or the other, in Buddhist, Hindu and Jain texts, the first version being traceable to the Buddhist text Udana, dated to the mid 1st millennium BC. This parable revolves around how a group of blind men trying to understand the appearance of an elephant individually explore different sections of the animal and come away with radically different ideas of what it looks like.

In a discussion on the Buddha-Nature that appears in Chapter 39 (On Bodhisattva Lion’s Roar) of the translation into English by Kosho Yamamoto of the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana (Nirvana) Sutra, thought to have been compiled between 100 AD and 220 AD, for example, there is a story in which a king asks his minister to show an elephant to a group of blind people and then asks them what the elephant was like.

“The person who had touched its tusk said: ‘The elephant is like [a radish].’

The man who had touched its ear said: ‘The elephant is like a winnow.’

The one who had touched its trunk said: ‘The elephant is like a pestle.’

The person who had touched its foot said: ‘The elephant is like a handmill made of wood [or mortar].’

The one who had touched it by the spine said: ‘The elephant is like a bed.’

The man who had touched its belly said: ‘The elephant is like a pot.’

The man who had touched it by its tail said: ‘The elephant is like a rope.’”

The king then says,

“All these blind persons were not well able to tell of the form of the elephant. And yet, it is not that they did not say anything at all about the elephant. All such aspects of representation are of the elephant. And yet, other than these, there cannot be any elephant.”

The parable of the blind men and the elephant has been used more generally to show how knowledge, even when arrived at experientially or empirically, is partial, and can therefore be misleading.

The simplicity and genius of the story has meant that it has captured the imagination of people in many cultures and countries around the world. In Chinese, it is encapsulated in the idiom 瞎子摸象 (blind men feeling an elephant).(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

Isolated research in individual scientific disciplines risks gaining only partial knowledge, rather like the story of the blind men inspecting the elephant.

(在各自封閉獨立的學科中做研究,可能會有知識流於片段的危險,就像是瞎子摸象一般。)

There’s something I’m not quite understanding here. I feel like the proverbial blind man working out what an elephant looks like.

(這裡有一些我不太了解的東西。我覺得自己好像是在瞎子摸象。)

A ‘Dutch angle’ is a classic camera technique that has been used in filmmaking since the 1920s, when it was introduced to Hollywood by German Expressionists. Why is it called the Dutch angle if it’s actually German? In fact, it has no __1__ to the Netherlands. The term “Dutch” is widely believed to be a misinterpretation of “Deutsch,” which means German in the German language. In any event, the name stuck, and the Dutch angle remains a popular cinematic tool to this day. This technique involves tilting the camera on its x-axis, skewing the shot to create a sense of

A: After holding nine concerts in Kaohsiung and Taipei recently, “God of Songs” Jacky Cheung will stage three extra shows later this week. B: They’re compensation for the three shows he postponed last year due to illness. A: He also canceled three more shows in Guangzhou last month. His health is worrisome. B: When touring Guangzhou, he dedicated his hit “She Is Far Away” to late singer Khalil Fong. That’s so touching. A: Online music platform KKBOX has also launched a campaign to pay tribute to Fong. I can’t believe he died so young: he was only 41. A:

A: After “God of Songs” Jacky Cheung sang for late singer Khalil Fong recently, music streaming service KKBOX also paid tribute to Fong by releasing his greatest hits online. B: The 20th KKBOX Music Awards ceremony is taking place at the K-Arena in Kaohsiung tomorrow. Fong performed at the ceremonies in the past. A: Who are the performers this year? B: The performers include Taiwanese groups 911, Wolf(s), Ozone, Singaporean pop diva Tanya Chua, and K-pop group Super Junior. A: South Korean stars actually took four spots among KKBOX’s 2024 Top 10 singles, showing that K-pop is still

Dos & Don’ts — 想想看,這句話英語該怎麼說? 1. 能做的事都做了。 ˇ All that could be done has been done. χ All that could be done have been done. 註︰all 指事情或抽象概念時當作單數。例如: All is well that ends well. (結果好就是好。) All is over with him. (他已經沒希望了。) That’s all for today. (今天到此為止。) all 指人時應當作複數。例如: All of us are interested in his proposal. All of us are doing our best. 2. 我們這麼做有益於我們的健康。 ˇ What we are doing is good for our health. χ What we are doing are good for our health. 註︰以關係代名詞 what 引導的作為主詞的子句,動詞用單數。如: What he said is true. 3. 大家都沿著步道跑。 ˇ Everybody runs along the trail. χ Everybody run along the trail. 註︰everyone 是指一大群人,但在文法上一般用單數。 4. 桌上有一本筆記本和兩支筆。 ˇ There were two