Chinese practice

飲鴆止渴

(yin3 zhen4 zhi2 ke3)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

drinking poison in the hope of quenching one’s thirst

我們常用成語「飲鴆止渴」──喝毒藥以解渴,來形容人只圖解決眼前的困難,而不顧將來更大的禍患。這個故事是出自《後漢書.卷四八》中,關於霍諝的記載。

當霍諝只有十五歲的時候,他寫了一篇奏記為其舅宋光辯護──宋光遭人誣陷,說他篡改皇帝詔書,因而入獄。霍諝寫道,宋光出身官宦之家,是一位可靠的官員,現已居地方首長之高位,也幾乎沒犯過什麼錯──他問道,像這樣的一個人怎麼可能會冒著死罪私自竄改詔書?這樣的行為就好比是「止渴於酖毒」,自尋死路。「酖」通「鴆」,是一種毒酒,由浸泡鴆鳥的羽毛而製成。根據古代《山海經》記載,鴆鳥劇毒,因其喜食毒蛇。

在台灣閩南語中,也有意義類似的說法──「請鬼拿藥單」。古時看病方式為請大夫到家裡為病人把脈、開藥方,然後家屬拿藥方單去藥房抓藥,若人手不足,則請外人代勞。若不小心請到鬼幫忙去抓藥,則是死路一條。

英文片語「to drink from the poisoned chalice」所用的比喻,是源自莎士比亞的劇作《馬克白》。chalice是一種有腳座的盃狀容器,以chalice喝下毒藥,是古代死刑的一種。古希臘哲學家蘇格拉底被處死的方式,便是用chalice喝下毒芹。

馬克白及其妻共謀殺害蘇格蘭王鄧肯,好讓自己取而代之成為國王。馬克白心知鄧肯是位好君主,之所以謀殺他只是出於自己的野心,馬克白也知道正義可能會向他討回公道。《馬克白》中以chalice盛裝的毒藥,是現世報的隱喻。馬克白在第一幕第七場中說道:

We still have judgment here, that we but teach

Bloody instructions, which, being taught, return

To plague th’ inventor: this even-handed justice

Commends the ingredients of our poisoned chalice

To our own lips.

這也就是說,世道會以其人之道還治其人之身,因為若我們自己使出暴力,暴力只會反過來糾纏我們。正義對所有人一視同仁,我們若要別人喝下毒藥,最後我們也將被迫喝下同樣的毒藥。

現今「poison chalice」一詞,指的是起初似乎是件好事,但其實卻是壞事。

(台北時報編譯林俐凱譯)

人類發展出基因改造的農作物,到底是飲鴆止渴,還是解決糧食問題的解藥?

(Who knows whether genetically modified crops will be a poisoned chalice, or whether it will be an answer to food shortages.)

政府為救經濟而猛印鈔票,不啻是飲鴆止渴,反而造成通貨膨脹。

(The government wildly printing money is unlikely to help the economy, and is in fact more likely to lead to inflation.)

英文練習

to drink from the poisoned chalice

The Chinese idiom 飲鴆止渴 (drinking poison in the hope of quenching one’s thirst) is often used to describe how people attempt to solve an immediate problem but end up making matters worse. It derives from a story found in volume 48 of the Hou Han Shu (Book of the Later Han Dynasty), which records the biography of Huo Xu.

When he was only 15 years old, Huo wrote a letter to the emperor in defense of his uncle, Song Guang, who had been framed and thrown into prison, accused of tampering with an imperial edict. He wrote of how Song Guang was a reliable official hailing from a family of officials, had already attained high status as a senior local government official, and who had few faults. He asked why such a man would risk the death penalty through such a rash act, likening this behavior to “quenching your thirst with zhen poison (止渴於酖毒),” which was known to be lethal. The zhen (酖) refers to the alcoholic drink made from infusing the poisonous feathers of the legendary zhenniao bird (鴆), which the ancient Shanhaijing (Classic of the Mountains and Seas) records as acquiring its toxicity from eating poisonous snakes.

The Hoklo Taiwanese phrase 請鬼拿藥單 (to ask a spirit to collect your prescription) is used in a similar way. In traditional society, a sick person’s family would send for a doctor, who would write out a prescription for Chinese herbs. If nobody in the family was available, they would ask somebody else to run the errand. The phrase warns against inadvertently asking a spirit to help out, for that would be putting the sick person’s life in danger.

In English there is the phrase “to drink from the poisoned chalice,” a metaphor used in William Shakespeare’s play Macbeth. A chalice is a drinking vessel consisting or a bowl upon a stem foot. In the past, forcing somebody to drink poison from a chalice was sometimes used for the death penalty. The Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, for example, drank hemlock when sentenced to death.

In the play, Macbeth conspires with his wife to murder the Scottish King Duncan, in the hope of becoming king himself. He knows that Duncan is a good monarch, and that it is only selfish ambition that compels him to murder the king. Macbeth is aware of the risk of justice catching up with him, and the poison in the chalice he refers to is a metaphor for karmic retribution in this life. In Act 1, Scene 7, Macbeth says,

We still have judgment here, that we but teach

Bloody instructions, which, being taught, return

To plague th’ inventor: this even-handed justice

Commends the ingredients of our poisoned chalice

To our own lips.

That is, in this world, there will be repercussions, for if we ourselves teach violence, it will only come back to haunt us. Justice is applied equally, and in the end we shall be forced to drink the same poison we served to others.

Nowadays, a “poison chalice” is something that at first appears to be a blessing, but turns out to be negative.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

My promotion was a poisoned chalice. I now have twice as much work as I used to.

(我升官像是好事,但其實相反。現在我的工作量是以前的兩倍。)

Only time will tell whether the Brexit referendum was a good idea, or whether former UK prime minister David Cameron handed the country a poisoned chalice.

(英國舉行脫歐公投到底是好是壞,英國前首相卡麥隆推動該公投是否為飲鴆止渴,只有時間能夠給出答案。)

A: Wow, Les Miserables Staged Concert Spectacular is visiting Taiwan for the first time. B: Isn’t Les Miserables often praised as one of the world’s four greatest musicals? A: Yup. Its concert is touring Taipei from tonight to July 6, and Kaohsiung between July 10 and 27. B: The English version of the French musical, based on writer Victor Hugo’s masterpiece, has been a huge success throughout the four decades since its debut in 1985. A: The musical has never toured Taiwan, but going to the concert sounds like fun, too. A: 哇,音樂劇《悲慘世界》紀念版音樂會首度來台巡演! B: 《悲慘世界》……它不是常被譽為全球四大名劇之一嗎? A: 對啊音樂會將從今晚到7月6日在台北演出,從7月10日到27日在高雄演出。 B: 這部法文音樂劇的英文版,改編自維克多雨果的同名小說,自1985年首演以來,在過去40年造成轟動。 A:

Some 400 kilometers above the Earth’s surface, the “International Space Station” (ISS) operates as both a home and office for astronauts living and working in space. Astronauts typically stay aboard the station for up to six months and engage in groundbreaking research projects in various fields, such as biology, physics and astronomy. These projects help scientists understand life in space and contribute to advancements that benefit people on Earth. The ISS has experienced significant growth since construction began in 1998. The station’s design and assembly represent an extraordinary international collaboration among Canada, the European Union, Japan, Russia and the United States.

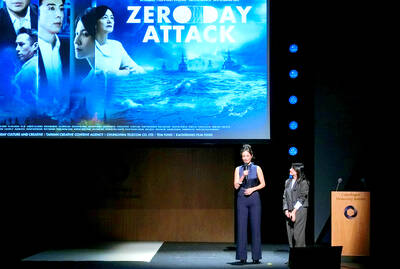

A: While hit musical Les Miserables’ concert tour kicks off, South Korean drama Squid Game 3 will be back at the end of this month. B: New Taiwanese dramas The World Between Us 2 and Zero Day Attack have also gained attention. A: I heard that Zero Day Attack is a story about the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Liberation Army trying to attack Taiwan by force. B: The drama’s subject is so sensitive that it has sparked a lot of controversy in society. A: I just hope that such a horrible story will never happen in

Continued from yesterday(延續自昨日) https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/lang Living on the ISS is challenging due to the absence of gravity. Astronauts must strap themselves into sleeping bags to prevent floating away while they sleep. They also spend about two hours exercising daily using specialized equipment. Despite this, microgravity can cause muscle loss, bone density reduction and cardiovascular changes. As a result, astronauts require extensive rehabilitation upon their return to Earth. In spite of these difficulties, astronauts often describe their experience on the ISS as life-changing. One of the most awe-inspiring aspects of living aboard the space station is the unparalleled view of Earth. Traveling at