Nobody can really say for certain when La Tomatina, the epic food fight fought entirely with tomatoes in the Spanish town of Bunol on the last Wednesday of August every year, actually started.

There is one theory, however: that it all began in 1945, during a parade in the village of people dressed as giants with massive heads. The story goes that one of the giants was accidentally knocked over by teenagers trying to join the parade and, enraged, picked a fight with them. The fight ended when the police intervened, but not after the kids started a precedent by pelting their giant assailant with tomatoes from a nearby market stall.

With the exception of a few years during which the event was banned, La Tomatina has been held annually in the village, attracting huge numbers of revelers from all over the world. Over time the event has become a victim of its own success, and numbers of people flocking to the village to take part have mushroomed to tens of thousands.

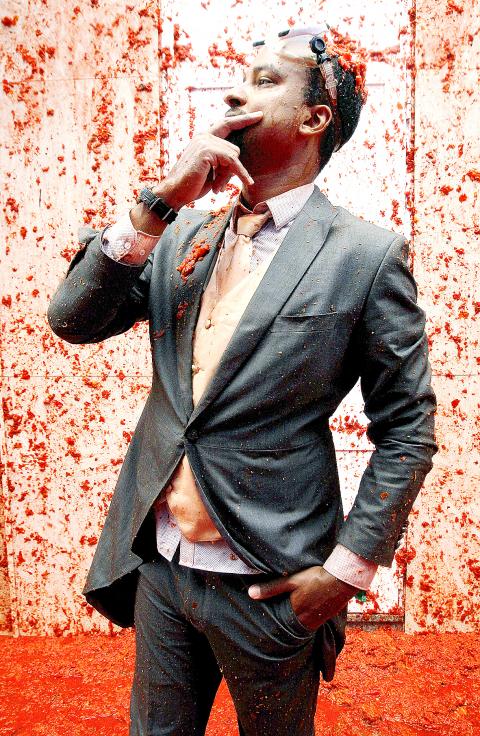

Photo: AP

照片:美聯社

Since 2013, visitors have needed a ticket to participate, with numbers restricted to 20,000. The fight itself begins at 11am and finishes 2 hours later. Tonnes of overripe tomatoes are trucked in, and local storekeepers put up plastic sheeting to protect their properties. When the festivities are over, the buildings are hosed down.(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

沒有人知道西班牙「番茄大戰」到底是從何時開始的,「番茄大戰」是每年八月最後一個星期三,在西班牙小鎮布尼奧爾舉行的盛典。在活動中,人們以蕃茄互相攻擊。

然而有此一說:一切都是從一九四五年村裡一場遊行開始的,參加該遊行的村民打扮成頭很大的巨人;其中一個巨人被想加入遊行的一群青少年不小心撞倒了,巨人一怒之下便跟這些青少年打起架來,直到警察介入方才停止。在這場混仗中這些青少年拿附近攤子上的番茄砸向巨人,而開啟了番茄大戰的先例。

Photo: AFP

照片:法新社

除了有幾年活動被禁,番茄大戰每年都舉辦,吸引了來自世界各地的龐大人群來到此鎮狂歡。該活動多年來愈見成功,反而造成了困擾,湧入村裡的人數迅速增加,已多達數萬人。

自二○一三年起,遊客須取得門票才能夠參加,門票數量為兩萬張。番茄大戰活動在上午十一點開始,兩小時後結束。一噸噸過熟的番茄運送進來,當地的店家們用塑料布遮住店鋪,以保護其財產不受損害。狂歡活動結束後,建築物便被沖洗乾淨。

(台北時報編譯林俐凱譯)

Photo: EPA

照片:歐新社

A: Apart from the musical Sunset Boulevard, Japanese pop diva Ayumi Hamasaki is also touring Taiwan after a 17-year wait. She’s holding two concerts starting tonight. B: Ayu has the most No. 1 hits of any Japanese solo artist, with 33 total. A: “Time” magazine even crowned her as “The Empress of Pop.” B: She staged shows in Taipei back in 2007 and 2008, causing an “Ayu fever” across Taiwan. A: Unfortunately, the singer has been deaf in her left ear since 2008, and is gradually losing hearing in her right ear. I’m so excited to see her singing in Taipei again. A: 除了音樂劇《日落大道》,日本歌后濱崎步睽違17年,今晚起在台北熱唱兩場。

Denmark’s state-run postal service, PostNord, announced that it would cease letter deliveries at the end of 2025 due to the impact of digitalization. As 95% of its residents now use the Digital Post service, Denmark has seen a 90% decline in letter volumes since 2000, from 1.4 billion to 110 million last year. On top of that, the Postal Act of 2024 removes the government’s obligation to provide universal mail service and puts an end to postal exemptions from value-added tax, raising the cost of a single letter to 29 Danish krone (US$4.20). As a result, PostNord is switching

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 “One DA-BEI... WU LONG... NAI?” Yujing smiled as the foreigner struggled to order. He looked like an embarrassed puppy. She repeated the order in Chinese, then English: “Oolong milk tea, large size. Half sweet, no ice?” she said gently. He beamed — the kind of full-face, sunshine smile that Latinos are famous for. “Yes! That! You are... lo maximo… the best!” After he left, Lily nudged her. “Nice save. You’re getting the hang of it.” Yujing had taken this summer job at the bubble tea shop to build confidence and get work

Although sending you an SMS (Short Message Service) verification code provides some security, many apps now use code-generating apps and two-factor authentication instead. But more recently, passkeys now use a biometric approach to logging in. Biometrics can offer an even more secure alternative. Following this trend, Google is reportedly planning to replace SMS verification codes with “QR code” scanning. SMS codes are currently used to verify user identity and prevent fraudsters from creating fake Gmail accounts to distribute spam. However, these codes present several challenges. They can be phished through suspicious links, and users may not always have access