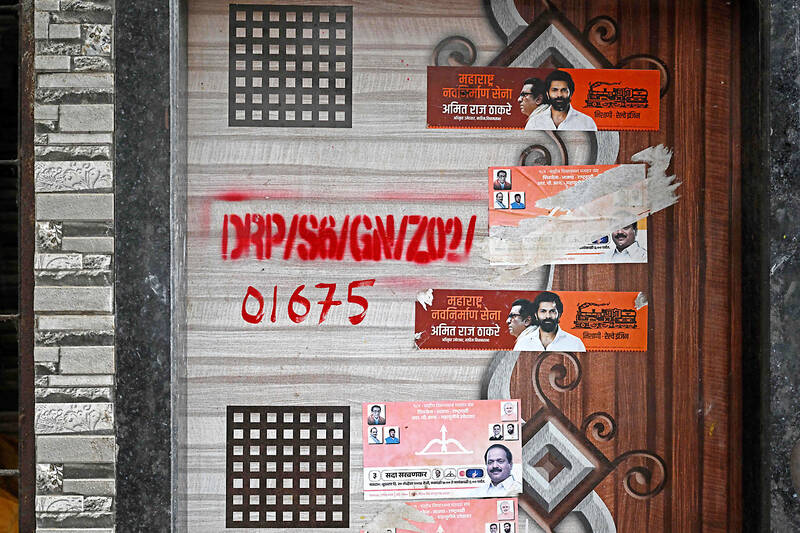

Stenciled just above the stairs, the red mark in Mumbai’s Dharavi slum is tantamount to an eviction notice for residents like Bipinkumar Padaya.

“I was born here, my father was born here, my grandfather was born here,” sighed the 58-year-old government employee.

“But we don’t have any choice, we have to vacate.”

Photo: AFP

Soon, bulldozers are expected to rumble into Asia’s largest slum, in the heart of the Indian megalopolis of Mumbai, flattening its labyrinth of filthy alleyways for a brand-new neighborhood.

The redevelopment scheme, led by Mumbai authorities and billionaire tycoon Gautam Adani, reflects modern India — excessive, ambitious and brutal.

If it goes ahead, many of Dharavi’s million residents and workers will be uprooted.

Photo: AFP

“They told us they will give us houses and then they will develop this area,” Padaya said.

“But now they are building their own planned areas and trying to push us out. They are cheating us.”

On the fringes of Dharavi, Padaya’s one-storey home is crammed into a tangle of alleys so narrow that sunlight barely filters through.

Photo: AFP

ENGINE ROOM AND UNDERBELLY

Padaya says his ancestors settled in the fishing village of Dharavi in the 19th century, fleeing hunger and floods in Gujarat, 600km to the north.

Waves of migrants have since swelled the district until it was absorbed into Mumbai, now home to 22 million people.

Today, the sprawl covers 240 hectares and has one of the highest population densities in the world — nearly 350,000 people per square kilometer.

Homes, workshops and small factories adjoin each other, crammed between two railway lines and a rubbish-choked river.

Over the decades, Dharavi has become both the engine room and the underbelly of India’s financial capital.

Potters, tanners and recyclers labor to fire clay, treat hides or dismantle scrap, informal industries that generate an estimated US$1 billion annually.

British director Danny Boyle set his 2008 Oscar-winning film Slumdog Millionaire in Dharavi — a portrayal that residents call a caricature.

For them, the district is unsanitary and poor — but full of life.

“We live in a slum, but we’re very happy here. And we don’t want to leave,” said Padaya.

‘CITY WITHIN A CITY’

A five-minute walk from Padaya’s home, cranes tower above corrugated sheets shielding construction. The redevelopment of Dharavi is underway — and in his spacious city-center office, SVR Srinivas insists the project will be exemplary.

“This is the world’s largest urban renewal project,” said the chief executive of the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP). “We are building a city within a city. It is not just a slum development project.” Brochures show new buildings, paved streets, green spaces, and shopping centers.

“Each single family will get a house,” Srinivas promised. “The idea is to resettle hundreds of thousands of people, as far as possible, in situ inside Dharavi itself.”

Businesses will also remain, he added — though under strict conditions.

Families who lived in Dharavi before 2000 will receive free housing; those who arrived between 2000 and 2011 will be able to buy at a “low” rate.

Newer arrivals will have to rent homes elsewhere.

‘A HOUSE FOR A HOUSE’

But there is another crucial condition: only ground-floor owners qualify.

Half of Dharavi’s people live or work in illegally built upper floors.

Manda Sunil Bhave meets all requirements and beams at the prospect of leaving her cramped two-room flat, where there is not even space to unfold a bed.

“My house is small, if any guest comes, it is embarrassing for us,” said the 50-year-old, immaculate in a blue sari.

“We have been told that we will get a house in Dharavi, with a toilet... it has been my dream for many years.”

But many of her neighbors will be forced to leave.

Ullesh Gajakosh, leading the “Save Dharavi” campaign, demands “a house for a house, a shop for a shop.” “We want to get out of the slums... But we do not want them to push us out of Dharavi in the name of development. This is our land.”

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not