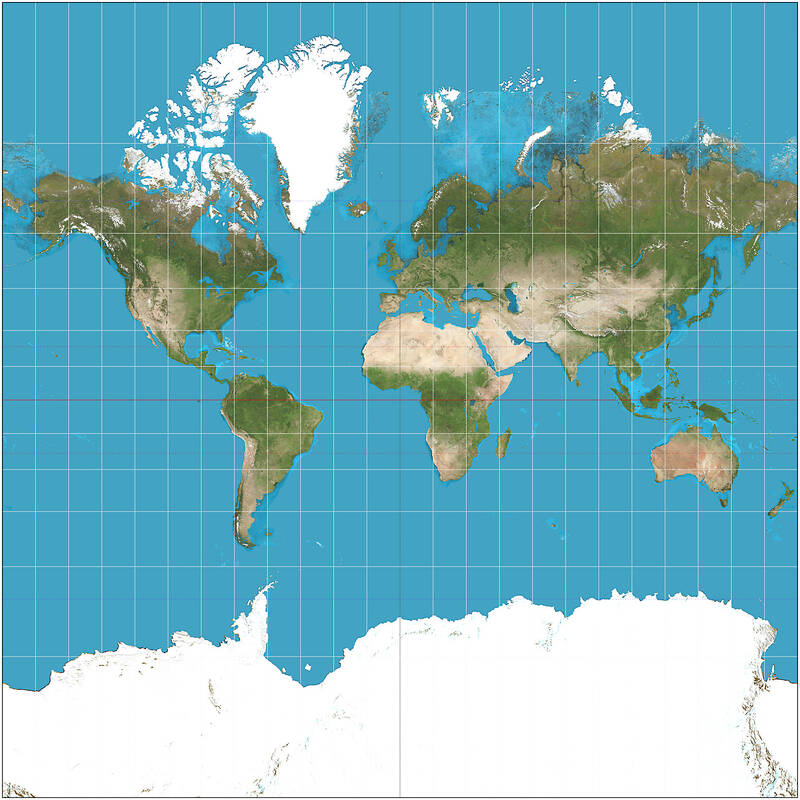

The Mercator world map, long a fixture in classrooms globally, makes the European Union appear almost as large as Africa. In reality, Africa is more than seven times bigger. It is a distortion that has prompted a new African initiative, “Correct the Map,” calling for depictions that show Africa’s true scale.

“For centuries, this map has minimized Africa, feeding into a narrative that the continent is smaller, peripheral and less important,” said Fara Ndiaye, co-founder of Speak Up Africa, which is leading the campaign alongside another advocacy group, Africa No Filter.

Accurately translating the Earth’s sphere into a flat map always calls for compromises, requiring parts to be stretched, cut or left out, experts said.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

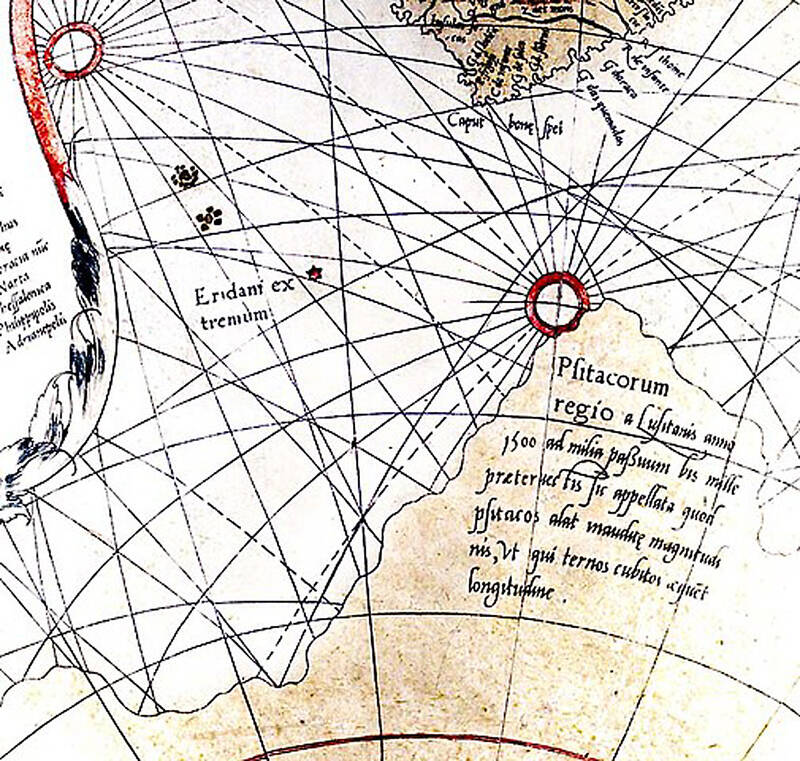

Historically, maps have reflected the worldview of their makers. Babylonian clay tablets from the sixth century BC placed their empire at the center of the world, while medieval European charts often focused on religious sites.

Choices must be made: a world map will look very different depending on whether Australia, Siberia or Europe is placed at its center.

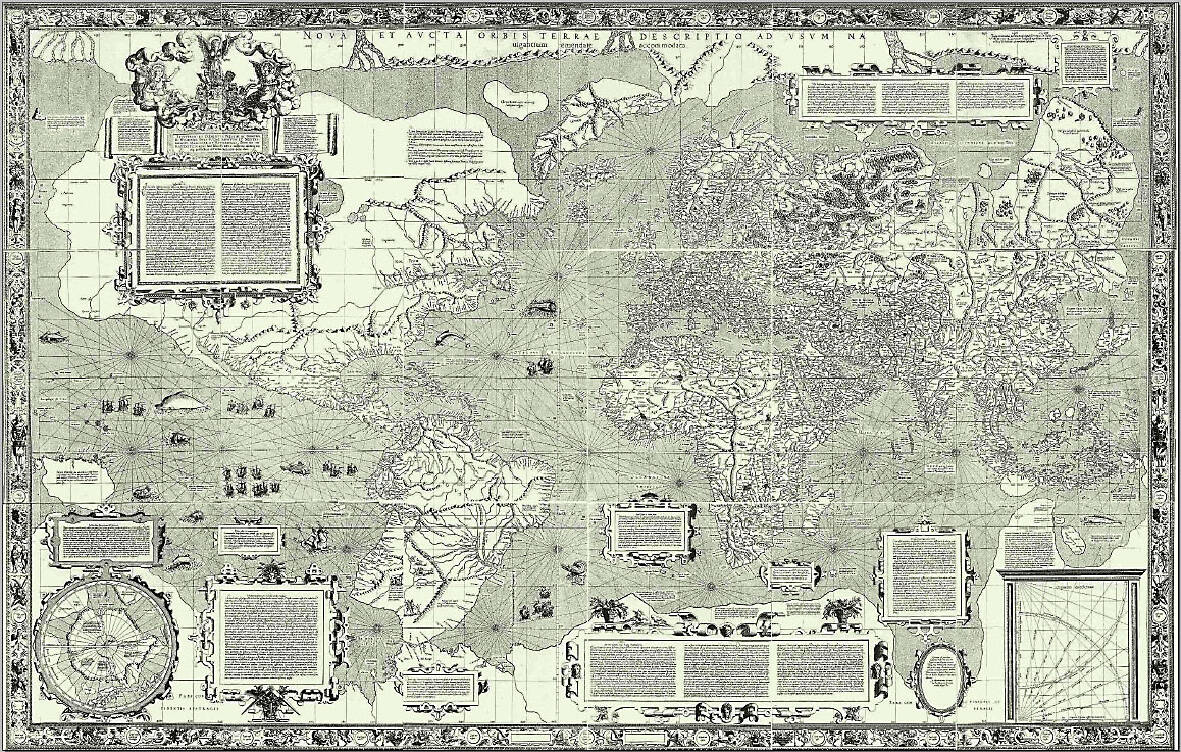

Today’s most-used map was designed for maritime navigation by Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569. It focused on accurate depictions of the shapes and angles of land masses, but their relative sizes were often inaccurate.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Mercator’s projection inflated northern regions and compressed equatorial ones, making Europe and North America appear much larger, while shrinking Africa and South America.

The distortions are stark: a 100-square-kilometer patch around Oslo, Norway, looks four times larger than the same area around Nairobi, Kenya. Greenland appears as large as Africa, even though it is 14 times smaller.

STRIKING A BALANCE

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Alternatives to the Mercator emerged in the 20th century, including one from 1921 by Oswald Winkel and another in 1963 by Arthur Robinson that reduced distortions but sacrificed precision. The 1970s Gall-Peters projection restored proportional sizes but stretched shapes.

To strike a balance between accuracy and aesthetics, cartographers Tom Patterson, Bojan Savric and Bernhard Jenny launched the Equal Earth projection in 2018. It makes Africa, Latin America, South Asia and Oceania appear vastly larger.

“Equal Earth preserves the relative surface areas of continents and, as much as possible, shows their shapes as they appear on a globe,” Savric said. This is the projection now endorsed by the African Union. Speak Up Africa says the next steps of their campaign are to push for adoption by African schools, media and publishers.

“We are also engaging the UN and UNESCO (its cultural body), because sustainable change requires global institutions,” Ndiaye said.

’NAIVE’ CONTROVERSY

Some critics reject claims of bias.

“Any claim that Mercator is flagrantly misleading people seems naive,” said Mark Monmonier, a Syracuse University geography professor and author of How to Lie with Maps. “If you want to compare country sizes, use a bar graph or table, not a map.”

Despite its distortions, Mercator remains useful for digital platforms because its focus on accurate land shapes and angles makes “direction easy to calculate,” said Ed Parsons, a former geospatial technologist at Google.

“While a Mercator map may distort the size of features over large areas, it accurately represents small features which is by far the most common use for digital platforms,” he said.

Having accurate relative sizes, as with the Equal Earth map, can complicate navigation calculations, but technology is adapting.

“Most mapping software has supported Equal Earth since 2018,” Savric said. “The challenge is usage. People are creatures of habit.”

Some dismiss the whole thrust of the African campaign. Ghanaian policy analyst Bright Simons says the continent needs more than a larger size on maps to “earn global respect.”

“South Korea, no matter how Mercator renders it, has almost the same GDP as all 50 African countries combined,” he said.

But advocates remain convinced of their cause. “Success will be when children everywhere open their textbooks and see Africa as it truly is: vast, central and indispensable,” Ndiaye said.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.