Something is thinning in public space. Pavements are still crowded. Parks still bustle. But if you look more closely — or, better still, if you measure it — the texture of our interactions has changed.

Together with colleagues at Yale, Harvard and other universities, we used AI to compare footage of public spaces from the 1970s with recent video in the same locations in New York, Boston and Philadelphia. The findings are striking: people walk faster, linger less and are less likely to meet up. That’s no surprise in a world where phones, Netflix and AI companions are luring us away from real-world spaces and real-world friends. Yet, if technology is part of the problem, it may also be part of the solution. By using AI to study urban public spaces, we can gather data, pick out patterns and test new designs that could help us rethink, for our time, our modern versions of the agora — the market and main public gathering place of Athens.

The urban playground has always drawn curious minds. Among the sharpest was William “Holly” Whyte, who filmed plazas and parks in 1970s New York. He was fascinated by where people chose to sit, how they navigated space, and what drew them together. His findings, documented in << Photo: AFP Whyte’s experiments were revelatory, but hard to replicate. Why? Analyzing the footage, frame by frame, took a team of assistants months. Now, finally, that challenge has been overcome, as we have invented non-human evaluators. Our team digitized Whyte’s original footage and compared it with recent videos — of Bryant Park, the steps of the Met Museum in New York, Boston’s Downtown Crossing and Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street — collected by sociologist Keith Hampton. Then we trained an AI model to analyze the two sets of footage. AI allows self-driving cars to recognize bikes and pedestrians; that same technology excels at analyzing footage of parks and plazas, and keeping track of hundreds of people at the same time. What took Whyte months now takes minutes. So how have cities changed between 1970 and 2010? As we discuss in a recent paper in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, walking speeds have increased by 15 percent. People stand still less often. Dyads — pairs meeting and then walking together — have declined. Downtown Crossing in Boston, once lively and social, has become a pass-through. Even in Manhattan’s Bryant Park — improved, according to Whyte’s vision — the number of social interactions has fallen. Cities have not emptied, but a part of their essence has thinned. Different forces have caused these changes. Work rhythms are accelerating and as time becomes more precious, we are less willing to spend it meandering. Perhaps people prefer Starbucks to the park. The iPhone was barely three years old in 2010, yet already we may have been pulled into our personalized data streams, abandoning the wandering gaze of the flaneur. Photo: AFP That could be a disaster for our social fabric. Online, we drift into curated echo chambers, scrolling past discomfort and filtering out dissent. Public space, by contrast, remains gloriously unfiltered. It invites friction, messiness, surprise. A rival football fan holds the door for you. Your children play with children who speak different languages. If we spend less time in public space, we might lose tolerance for the wider public — and thus lose the habit of citizenship itself. Paradoxically, the same technologies pulling us inward might help bring us back out. Social media is addictive because algorithms are constantly testing out what we like. If we use AI to analyze outdoor public spaces, we can do the next best thing: give every park, plaza and street corner its own, personal William Whyte to test improvements there. What types of chairs and benches best promote interaction? Could adding greenery or water features create a more comfortable microclimate? Which public games might help break the ice? Temporary design interventions could be introduced, evaluated with AI, and iterated through a process of trial and error — evolving organically, much like nature itself. To this end, architects should not shy away from using new AI tools, as we argue at this year’s Biennale Architettura in Venice. But how? First, with humility. Public spaces of the past were far from perfect — often excluding women, minorities and those with access needs. We should not romanticize them. Nor should we surrender to a technology-led present. Optimizing public life through data alone risks repeating the mistakes of high modernism. AI can reveal patterns. It cannot dictate what is good. Second, with curiosity. Public space is not static. It is alive. It responds to heat, light, geometry, program. Small interventions — a bench in shade, a water fountain on a hot day, a winding path instead of a shortcut — can transform behavior. In a recent study in Milan, we found that compliance with 30km/h speed limits had less to do with signage and more to do with street geometry. What slows us down is not instruction but design. Climate change, too, plays a growing role. As temperatures rise across southern Europe, many urban spaces remain shaped by outdated climatic expectations. Sicily can now grow mangoes, yet its squares offer little protection from heat. We might learn from cities such as Singapore, where the orchestration of vegetation, water, and shading are used to actively mitigate heat. If Europe’s climate is changing then its public spaces must follow. The deeper challenge is this: for too long, designers have worked at a remove — imagining how people should behave from studios located far from the street. Today, we have tools to observe how people actually behave. To test hypotheses. To prototype joy and proximity. Yet these tools must be used not for optimization but for stewardship. If we can use them wisely, we can counter the hollowing of public space. The agora isn’t dead. It just needs redesigning. And if we’re smart about it, AI might just help us get there. It may help us hear something else too: the fragile, elusive symphony of the commons.

A view on May 21, 2021 of Little Island, a free public park in Hudson River Parkin New York City.

A view on May 21, 2021 of Little Island, a free public park in Hudson River Parkin New York City.

Has the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) changed under the leadership of Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌)? In tone and messaging, it obviously has, but this is largely driven by events over the past year. How much is surface noise, and how much is substance? How differently party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) would have handled these events is impossible to determine because the biggest event was Ko’s own arrest on multiple corruption charges and being jailed incommunicado. To understand the similarities and differences that may be evolving in the Huang era, we must first understand Ko’s TPP. ELECTORAL STRATEGY The party’s strategy under Ko was

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

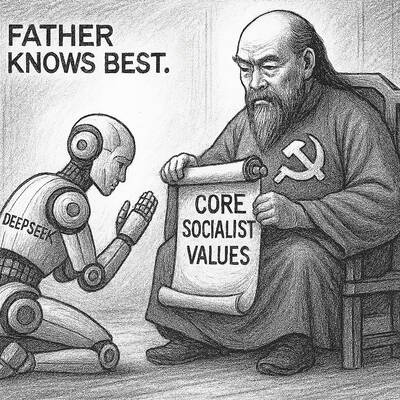

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

It turns out many Americans aren’t great at identifying which personal decisions contribute most to climate change. A study recently published by the National Academy of Sciences found that when asked to rank actions, such as swapping a car that uses gasoline for an electric one, carpooling or reducing food waste, participants weren’t very accurate when assessing how much those actions contributed to climate change, which is caused mostly by the release of greenhouse gases that happen when fuels like gasoline, oil and coal are burned. “People over-assign impact to actually pretty low-impact actions such as recycling, and underestimate the actual carbon