A heatwave scorching Europe had barely subsided early last month when scientists published estimates that 2,300 people may have died across a dozen major cities during the extreme, climate-fueled episode.

The figure was supposed to “grab some attention” and sound a timely warning in the hope of avoiding more needless deaths, said Friederike Otto, one of the scientists involved in the research.

“We are still relatively early in the summer, so this will not have been the last heatwave. There is a lot that people and communities can do to save lives,” said Otto, a climate scientist at Imperial College London.

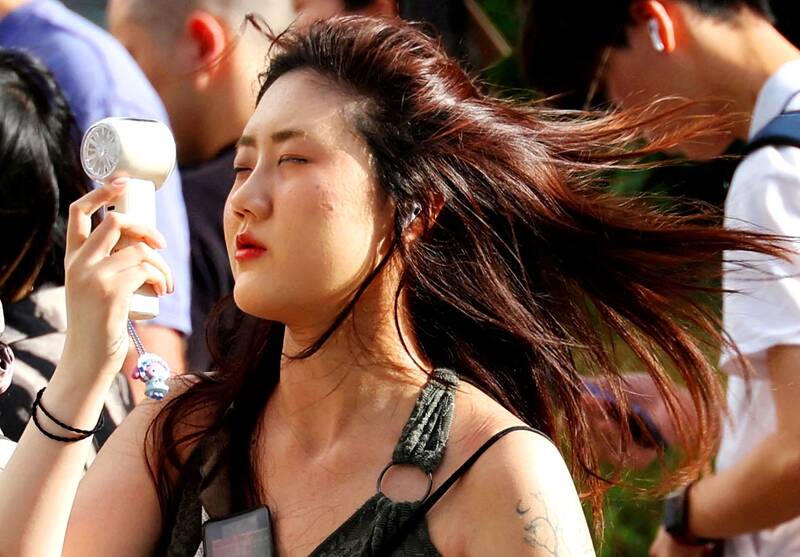

Photo: Reuters

Heat can claim tens of thousands of lives during European summers but it usually takes months, even years, to count the cost of this “silent killer.”

Otto and colleagues published their partial estimate just a week after temperatures peaked in western Europe. While the underlying methods were not new, the scientists said it was the first study to link heatwave deaths to climate change so soon after the event in question.

Early mortality estimates could be misunderstood as official statistics but “from a public health perspective the benefits of providing timely evidence outweigh these risks,” said Raquel Nunes from the University of Warwick.

“This approach could have transformative potential for both public understanding and policy prioritization” of heatwaves, said Nunes, an expert on global warming and health who was not involved in the study.

BIG DEAL

Science can show, with increasing speed and confidence, that human-caused climate change is making heatwaves hotter and more frequent.

Unlike floods and fires, heat kills quietly, with prolonged exposure causing heat stroke, organ failure and death.

The sick and elderly are particularly vulnerable, but so are younger people exercising or toiling outdoors. But every summer, heat kills and Otto — a pioneer in the field of attribution science — started wondering if the message was getting through.

“We have done attribution studies of extreme weather events and attribution studies of heatwaves for a decade... but as a society we are not prepared for these heatwaves,” she said. “People think it’s 30 (degrees Celsius) instead of 27, what’s the big deal? And we know it’s a big deal.”

When the mercury started climbing in Europe earlier this summer, scientists tweaked their approach.

Joining forces, Imperial College London and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine chose to spotlight the lethality — not just the intensity — of the heat between June 23 and July 2.

Combining historic weather and published mortality data, they assessed that climate change made the heatwave between 1 degree Celsius and 4 degrees Celsius hotter across 12 cities, depending on location, and that 2,300 people had likely perished.

But in a notable first, they estimated that 65 percent of these deaths — around 1,500 people across cities including London, Paris and Athens — would not have occurred in a world without global warming.

“That’s a much stronger message,” Otto said.

“It brings it much closer to home what climate change actually means and makes it much more real and human than when you say this heatwave would have been two degrees colder.”

UNDERESTIMATED THREAT

The study was just a snapshot of the wider heatwave that hit during western Europe’s hottest June on record and sent temperatures soaring to 46 degrees Celsius in Spain and Portugal.

The true toll was likely much higher, the authors said, noting that heat deaths are widely undercounted.

Since then Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria have suffered fresh heatwaves and deadly wildfires.

Though breaking new ground, the study has not been subject to peer review, a rigorous assessment process that can take more than a year.

Otto said waiting until after summer to publish — when “no one’s talking about heatwaves, no one is thinking about keeping people safe” — would defeat the purpose.

“I think it’s especially important, in this context, to get the message out there very quickly.”

The study had limitations but relied on robust and well-established scientific methodology, said several independent experts.

Tailoring this approach to local conditions could help cities better prepare when heatwaves loom, said Abhiyant Tiwari, a health and climate expert

July 28 to Aug. 3 Former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly maintained a simple diet and preferred to drink warm water — but one indulgence he enjoyed was a banned drink: Coca-Cola. Although a Coca-Cola plant was built in Taiwan in 1957, It was only allowed to sell to the US military and other American agencies. However, Chiang’s aides recall procuring the soft drink at US military exchange stores, and there’s also records of the Presidential Office ordering in bulk from Hong Kong. By the 1960s, it wasn’t difficult for those with means or connections to obtain Coca-Cola from the

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

A couple of weeks ago the parties aligned with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), voted in the legislature to eliminate the subsidy that enables Taiwan Power Co (Taipower) to keep up with its burgeoning debt, and instead pay for universal cash handouts worth NT$10,000. The subsidy would have been NT$100 billion, while the cash handout had a budget of NT$235 billion. The bill mandates that the cash payments must be completed by Oct. 31 of this year. The changes were part of the overall NT$545 billion budget approved

Trolleys piled high with decapitated silicon monster heads, tattooed dealers lurking in alleyways, bin bags of contraband hidden behind shop counters: welcome to the world of Lafufus. Fake Labubus (拉布布), also known as Lafufus, are flooding the hidden market. As demand for the collectable furry keyrings soars, entrepreneurs in the southern trading hub of Shenzhen are wasting no time sourcing imitation versions to sell to eager Labubu hunters. But the Chinese authorities, keen to protect a rare soft-power success story, are cracking down on the counterfeits. “Labubus have become very sensitive,” says one unofficial vendor, in her small, unmarked, fake designer goods