As the world has raced to understand how Taiwan can be both the world’s most important producer of semiconductors while also the pin in the grenade of World War III, a reasonable shelf of “Taiwan books” has been published in the last few years. Most describe Taiwan according to a power triangle dominated by the US and China. But what of the actual Taiwanese themselves? Who are they? And should they have any say in the matter?

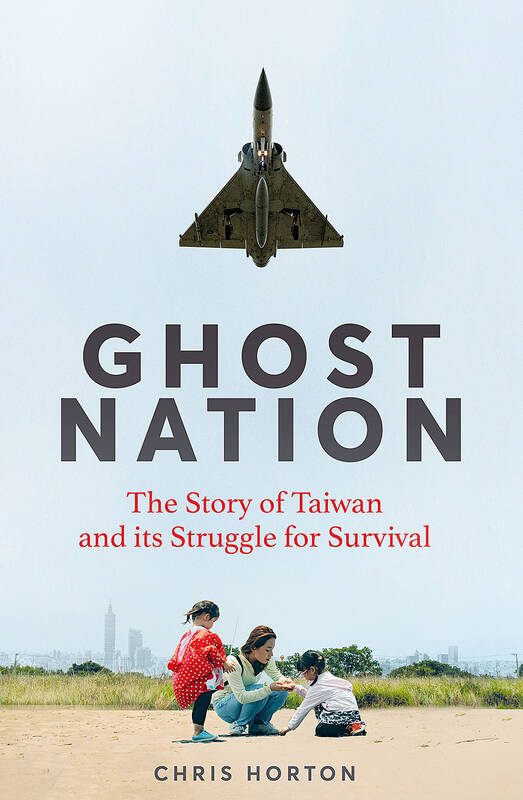

Chris Horton’s Ghost Nation: The Story of Taiwan and Its Struggle for Survival is perhaps the first general history of Taiwan to answer these questions and do justice to its people and their long fight to build Asia’s most vibrant democracy. Not only is it a compelling read, it’s one that is utterly crucial for understanding both Taiwan’s domestic politics and global importance today.

For the last decade, Horton has reported from Taiwan for the New York Times, the Guardian and the Atlantic, where he once described the nation’s predicament — that of an independently governed territory vital to the world economy but only given full diplomatic recognition by only about a dozen UN member states — as a “geopolitical absurdity.”

In Ghost Island, Horton covers Taiwan from disputes over ancient territorial claims to semiconductors and current tensions with Beijing, but where he really shines is in a long overdue history of Taiwan’s road to democracy.

PROTO DEMOCRACY

Proto-movements for Taiwanese self-determination emerged during the island’s Japanese colonial era — in 1923, Taiwan’s first pilot, Hsieh Wen-ta (謝文達), dropped a load of political leaflets over Tokyo as part of a campaign for local representation in government — but today Taiwan’s sense of unique identity is largely defined against the island’s occupation by Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies following World War II.

When Chiang retreated to Taiwan in 1949, bringing with him more than a million soldiers, bureaucrats and refugees, he established rule over a population that was by then mainly Hokkien and Hakka Chinese, immigrants from south China during the previous 300 years who’d intermixed with what was by then a small minority of indigenous Austronesian peoples.

These “native born Taiwanese,” who’d become prosperous and educated under Japanese colonial rule, were alarmed by the arriving KMT troops, a ragged, shambling bunch who were not only unsanitary — they reintroduced both bubonic plague and cholera to Taiwan — but were also horribly corrupt, looted everything in sight and spoke Chinese dialects that were to all intents completely different languages.

Tensions between the two populations, the “native born” benshengren (本省人) and the “foreign born” waishengren (外省人), boiled over in February 1947, when a street scuffle exploded into a KMT massacre of thousands of native Taiwanese. (No full accounting of the slaughter has ever been made.)

This original trauma, now known as the 228 Incident and referred to by some waishengren as their “original sin,” was a defining national moment for the Taiwanese comparable to the atomic bombs of World War II for the Japanese or 9-11 for America. In subsequent decades, the memory of 228, hardened by 38 years of KMT military rule and White Terror, coalesced as a raison d’etre for movements for Taiwanese identity and democratic self-determination, notions that most Taiwanese citizens hold self-evident today.

DEMOCRACY MOVEMENTS

Under a repressive military regime, Taiwan’s first major democracy movements sprung up in exile, with the earliest in Japan. There in 1962, Su Beng (史明), who’d conspired to assassinate Chiang Kai-shek a decade earlier, published a seminal treatise on Taiwanese identity, Taiwan’s 400 Year History. In it, he argued that a distinct Taiwanese identity had been forged by four centuries of colonization by Dutch, French, Spanish, and Japanese.

Two years later, Peng Ming-min (彭明敏), a native Taiwanese who’d become a rising star as a KMT technocrat, became one of the first to broach nativist ideas within Taiwan. Aged 39, he issued a manifesto, “A Declaration of Taiwanese Self-Salvation” that called for the end of Chiang Kai-shek’s plans to retake China, a new constitution for the island nation and the acknowledgment that Taiwan and China were separate countries.

The KMT rewarded Peng with imprisonment, but after six years he escaped into exile in the US. There he continued to write, and, following Taiwan’s 1971 expulsion from the UN, he charged in an op-ed for the New York Times that Taiwan’s leaders “must learn to distinguish ethnic origin and culture from politics and law, and to discard their archaic obsession to claim anyone of Chinese ancestry as legally Chinese, however far removed from China.”

Overseas voices like Peng and Su emboldened Taiwan’s domestic activists. In 1979, a group, believing that Taiwan must forge its own future after the US cut diplomatic ties the previous year, launched a new publication, Formosa Magazine, as a mouthpiece for their still somewhat underground political movement, the tangwai (黨外) or “outside of the party” movement.

Formosa Magazine’s offices, located in major cities around the island, effectively acted as a network of political offices that would later evolve into Taiwan’s first pro-democracy opposition party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). In the magazine’s first issue, they declared, “we believe that it is no longer the right of any regime or the literati it nurtures to decide our future path and destiny, but the right of all of us, the people.”

After four issues and explosive publication runs, the KMT banned the magazine and, in military courts, convicted its leaders, the “Kaohsiung Eight,” of sedition with sentences of ten years to life in prison.

But before any could serve their full time, the KMT ended martial law in 1987, and most sentences were commuted. The DPP formally came into being in 1986, and for the following two decades, Kaohsiung Incident activists dominated its leadership. One of the defense lawyers, Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), went on to become Taiwan’s first DPP president in 2000. For his vice president he chose the magazine’s editor, Annette Lu (呂秀蓮).

PARTISAN PERSPECTIVE

Horton details this part of Taiwan’s story wonderfully, but it’s important to note that he does so as a partisan of the DPP’s independence-leaning green camp.

The KMT is meanwhile cast as a one-dimensional bogeyman, and this is a flaw. While KMT oppression was deplorable, the party did facilitate Taiwan’s economic miracle, allow degrees of social liberalization and permit independent, non-KMT mayors of several cities, including Taipei, from the 1950s to the 1970s. By uniformly disparaging the century-old party, it makes it difficult to understand why it remains a viable, powerful force in Taiwan’s politics today.

Ghost Nation also suffers from a jerky structure, and if you don’t track Taiwan’s politics, some references may be hard to follow. But all told, there is no better general history of modern Taiwan currently on the market.

This is especially true when it comes to current China tensions. Here, Horton forcefully blames the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for its threats to destroy Taiwan and its hard-won democracy. But he also dares to remind us, “It is not the CCP that has erased Taiwan, it is us: the liberal democracies, the developed economies, the supposed friends of Taiwan. We have ghosted Taiwan, and in doing so, have lost a little of our own humanity.”

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just