Looking back to 2022, it seems impossible that anyone ever believed that Brian “Liver King” Johnson achieved his physique without pharmaceutical assistance. He looks like a hot water bottle stuffed with bowling balls, an 80s action figure with more veins — an improbably muscular man who put his bodybuilder-shaming physique down to a diet of “raw liver, raw bone marrow and raw testicles.”

And that last part, really, was the trick: by crediting his results to a regime that nobody else would dare try, he gave them a faint veneer of plausibilty. Maybe, if you followed a less extreme version of his protocol, you could get comparable (though less extreme) results. And if you couldn’t stomach an all-organ diet, well, you could always get the same nutrients from his line of supplements.

The Liver King, of course, was dethroned — leaked emails revealed that he was spending more than US$11,000 a month on muscle-building anabolic steroids, as detailed in a new Netflix documentary. But the story of a charismatic person promising ridiculous results is just the most outrageous example of a phenomenon that’s been around ever since performance enhancers were invented. In the 1980s, Hulk Hogan urged a generation to say their prayers and eat their vitamins in his VHS workout set; then in 1994 he was forced to admit to more than a decade of steroid use during a court case against his former boss, Vince McMahon.

Photo: AFP

Today, influencers post their morning ice baths and deep breathing exercises, but don’t mention what they’re injecting at the same time, whether that’s steroids intended to encourage muscle growth in the same way that testosterone does, or testosterone itself, or human growth hormone (HGH). As a result, a generation of young men and women — and, to be fair, plenty of middle-aged ones — are developing a completely skewed version of what’s possible with hard work and a chicken-heavy diet. And things might be getting worse, not better.

‘APPEALING PLACE’

It’s never been easier to start a business based on your body. With a couple of hundred thousand followers and a decent angle, it only takes a couple of days to whip up an ebook, online course or meal plan. Apps make it easy to start group coaching or habit-tracking services, and even supplement companies are easy to start, if you’re happy to just stick your own label on tubs of protein powder.

“In the current economic climate, the fitness industry is a very appealing place,” says James Smith, a personal trainer, fitness influencer and bestselling author who has been open about using steroids in his early 20s (he’s now 35).

“If you’ve got decent genetics, you’re a decent coach and have a grasp of marketing, you can unlock a very good income selling workouts and training plans. So maybe you take a little bit of testosterone to get a little leg up, and suddenly you’re getting compliments at the gym and posting record lifts on Instagram. Surely a bit of human growth hormone couldn’t hurt? OK, business is now at an all-time high; followers are coming up to you and asking about reps and sets. You’ve dug yourself a hole that is hard to get out of. What do you do now? Tell your audience you’re on steroids?”

If you did, you’d be in a very small minority. There are — at a conservative estimate — tens of thousands of fitness influencers globally, and only a small handful have openly admitted to using steroids, even among those posting the most outlandish results. Larry Wheels, an influencer and powerlifter, talked about the muscle cramps, depression, lethargy, loss of appetite and low libido he suffered from steroid abuse in a 2018 video. He then announced he was no longer taking them in 2022, followed by a relapse last year.

Sam Sulek, one of the current kings of fitness on YouTube thanks to his combination of chatty, informal videos and unbelievable physical dimensions, hasn’t elaborated, but in a video last year he did tell fans he’d be unable to reach his goal weight of 300lb “natural.”

Rich Piana, famed for inventing an arms workout taking eight hours, was open about his steroid use for much of his career, discussing his own “cycle” and giving out advice for other users on social media. He died in 2017, aged 46, and with a heart weighing twice the normal amount for an adult male.

But while a high-profile handful of people decide to open up, most other influencers continue to maintain that they’re “natural” or just avoid the subject entirely. A few even take tests to “prove” they’re clean, ignoring the fact that tests are easy to cheat: most steroids are undetectable after a weightlifter cycles off them for a month or so, while their effects can linger in the body for ever. And, make no mistake, the effects of enhancement can be huge: in one study, a group of men who took 600mg of testosterone enanthate for 10 weeks and did no exercise saw greater gains in strength than a placebo group who took nothing and worked out normally.

“In my first cycle of testosterone in my early 20s, I climbed the status hierarchy in 12 weeks,” says Smith. “I didn’t use steroids to benefit my business, but I completely understand why people do it. It sounds bad to say, but if you want to ever make a living from fitness, you’re almost stupid for even trying to do it naturally.”

‘I DON’T WANT TO BE THAT PERSON’

Meanwhile, it’s not just influencers getting bigger who might be misrepresenting how they achieve their unbelievable results. Last month, Peloton instructor Janelle Rohner agreed to refund followers who bought her course on food macros, after admitting to using GLP-1 weight loss drugs.

“I could have kept this a secret,” she said in a TikTok video posted after the subsequent backlash. “I could have gone on and on for years and not told, but I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to be that person.”

The implication, of course, is that plenty of people are prepared to be that person, and it’s hard to argue. In the years since Wegovy and similar drugs have been approved for weight loss, plenty of influencers have undergone near-miraculous transformations, most of them citing clean eating when it’s possible they’re doing the exact opposite. At the same time, some influencers are taking a far more dangerous route than pills or chemicals — injecting synthol, an oil used to bulk up their muscles, or having high-risk “Brazilian butt lifts” to compensate for bodies that won’t change naturally.

How much of any of this is a problem if you, personally, are blissfully unaffected by every For anyone who takes online influencers at their word, training can feel dispiriting and hopeless: even working out multiple times a day and eating perfectly, it can be impossible to reach the same levels of fat-free muscle as your Instagram feed will show you after 20 seconds of scrolling. And, of course, film stars male and female are hardly helping the situation by showing up more lean and muscular than they’ve ever been in their 40s or 50s, preaching the virtues of twice-a-day training and drinking lots of water. “It’s quite clear there’s been an uptick in this stuff,” says Dan Roberts, a personal trainer who works with actors and Broadway stars. “It takes time to build muscle, so when you suddenly build a lot of it, that’s not possible without extra testosterone in your system, or growth hormone, or something. Also, sometimes the signs are just really obvious … when someone’s neck thickens up suddenly …” FIGHTING BACK Some fitness enthusiasts, meanwhile, are fighting back. In Reddit’s “natty or juice” community, members debate whether celebrities and influencer physiques are achievable naturally, or if their results show signs of substance abuse: a distended stomach (sometimes known as “roid gut”) can be a sign of excess growth hormone, while gynecomastia (an increase of breast gland tissue in men) is typically caused by an imbalance in hormone levels. On YouTube, bodybuilders and coaches such as Greg Doucette, Dr Mike Israetel and Derek Munro (whose channel, More Plates More Dates, exposed the Liver King) explain what actually goes into a serious steroid regime, as well as the disastrous possible side-effects. But even with millions of viewers well versed in the minutiae of Winstrol or the signs of an HGH habit (it’s all in the jaw), millions more hang on to the hope that the right protein powder or workout regime might be enough, and end up hopelessly disappointed. So what’s the solution? A good start would be for the most high-profile influencers and celebrities to be honest about what they’re using and the risks they’re accepting to do it. “Look at testosterone,” says Smith, who posted a video about his own regime earlier this year. “It’s cheap, easily accessible, well tolerated and arguably less dangerous than a lot of other things young people do. There are multiple implications for using it over the long term, problems with use versus abuse, fertility and many other psychological implications and impacts to using it, but it’s absolutely becoming more common. I look better with my shirt off at 35 than 25 because I now use a TRT [testosterone replacement therapy] service.” We could also reframe what we’re looking to get out of exercise, from an enviable physique to a better quality of life. “When it comes to our health, there are so many actually proven things we can do to live longer, be happier, fitter, stronger,” says Roberts. “The good information is out there — we just have to look for it through all the noise and nonsense.” We should also probably ignore the people who have lied to us in the past. The Liver King has now, in a way, come clean: after claiming to go “natty” for 60 days in an Instagram post, he admitted to being back on steroids in late 2023 (although he is still preaching the value of his “nine ancestral tenets,” which include sleep, sun exposure and cold therapy, and which the Netflix documentary claims were made up in conjunction with his marketing agency). “I think he thought the broader message was more important than the steroids,” says Ben Johnson, former CEO of the Liver King’s holding company, Tip of the Spear, who seems genuinely shocked that his former associate was doing anything untoward. “It’s unfortunate that the messenger has killed the message … when there’s a kernel of truth at the center of the message, it’s easy to focus on that and ignore the other variables.” What isn’t quite so easy is looking past the abs and the arms, and finding people who value health and wellbeing over aesthetics and false promises. But as anyone who’s put in the work knows, sometimes the hard path is the one that pays off.

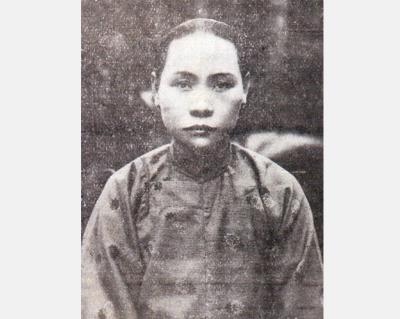

Dec. 8 to Dec. 14 Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.” She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽). While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

Politics throughout most of the world are viewed through a left/right lens. People from outside Taiwan regularly try to understand politics here through that lens, especially those with strong personal identifications with the left or right in their home countries. It is not helpful. It both misleads and distracts. Taiwan’s politics needs to be understood on its own terms. RISE OF THE DEVELOPMENTAL STATE Arguably, both of the main parties originally leaned left-wing. The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) brought together radicals, dissidents and revolutionaries devoted to overthrowing their foreign Manchurian Qing overlords to establish a Chinese republic. Their leader, Sun Yat-sen

Late one night in April 2020, towards the start of the COVID lockdowns, Shanley Clemot McLaren was scrolling on her phone when she noticed a Snapchat post by her 16-year-old sister. “She’s basically filming herself from her bed, and she’s like: ‘Guys you shouldn’t be doing this. These fisha accounts are really not OK. Girls, please protect yourselves.’ And I’m like: ‘What is fisha?’ I was 21, but I felt old,” she says. She went into her sister’s bedroom, where her sibling showed her a Snapchat account named “fisha” plus the code of their Paris suburb. Fisha is French slang for