Books that attempt to explain Taiwan in an accessible manner have proliferated in recent years. This can be traced to Nancy Pelosi’s 2022 visit to Taipei and China’s belligerent reaction, increasing the attention paid to Taiwan in international media and efforts to explain the country’s peculiar status. By focusing on Taiwanese voices and Taiwan as a distinct entity, rather than a pawn in great power politics, Jonathan Sullivan and Lev Nachmann made a worthy attempt at communicating the country in Taiwan: A Contested Democracy Under Threat (reviewed in Taipei Times, Oct. 5, 2023). Taking almost the opposite tack, in The Struggle for Taiwan (reviewed in Taipei Times Aug. 29, 2024), Sulmaan Wasif Khan examines the Cold War foundations of Taiwan’s status.

Other books have outlined Taiwan’s importance for specific audiences — Europe in the case of Zsuzsa Anna Ferenczy’s Partners in Peace: Why Europe and Taiwan Matter to Each Other (reviewed in Taipei Times, Nov. 28, 2024), and the world at large in Kerry Brown’s The Taiwan Story (watch this space for review).

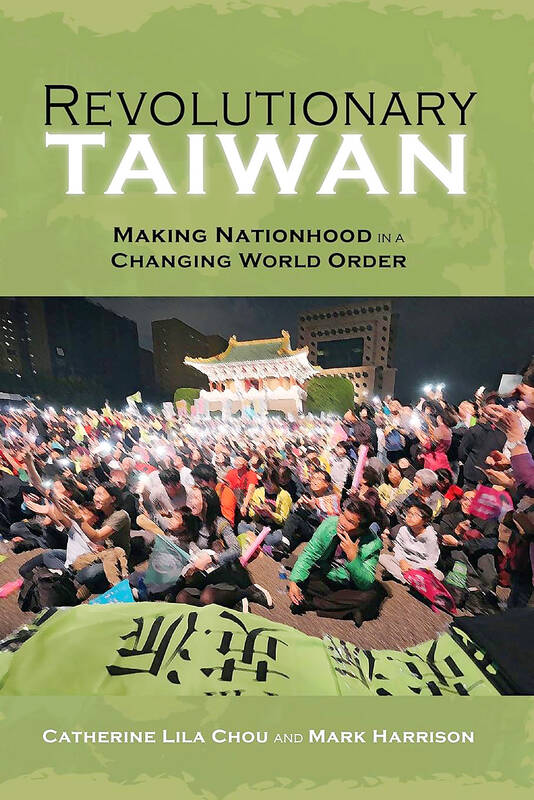

All of these have merits, but none are close to what Catherine Lila Chou and Mark Harrison have achieved in Revolutionary Taiwan: Making Nationhood in a Changing World Order. Not only does this book convey Taiwan in the “readably academic” way that the authors intended, it uses a novel yet practical approach.

As they explained in a recent book talk, hosted by the Australasian Taiwan Studies Association, the authors met virtually via X (formerly known as Twitter), where, in Chou’s words, even “before Elon Musk purchased the platform,” the conversations about Taiwan could be “bruising and brawling.” Online interaction was also at the heart of the collaborative writing process, with the book taking shape via Google Meets.

Aside from the mutual appreciation of what Harrison calls, in Chou’s case, a “remarkable commitment to engaging in substantive debates” about Taiwan with “not the most sympathetic interlocutors,” Chou and Harrison had already admired each other’s work from afar. Harrison’s 2018 paper “Art, violence, and memory in Taiwan,” had caught Chou’s attention for its challenge to standard accounts of the struggle against authoritarianism as “an evolutionarily bloodless transition to democracy,” in which the “economic miracle and political miracle” are foregrounded, but the “element of violence” that occurred often remains “hidden.”

CUBA COMPARISON

By the same token, an online article by Chou resonated with Harrison. Titled “The 228 Inheritance: Taiwan’s Revolution Is Here,” the short essay argued that Taiwan’s revolution was “open-ended” and fought on three fronts — “against the annexationist desires of the PRC; the continuing occupation of the KMT’s Republic of China; and the legacies of dispossession and discrimination left by Taiwan’s history as an early modern settler colony.”

In the book talk, Chou mentioned a trip to Cuba, which got her thinking about the nature of revolution. Visiting in 2019 while the country was celebrating the 60th anniversary of its own revolution, Chou was struck by the question of what it means to achieve ultimate victory in such a struggle or for it to be officially over. While very different countries, there was “some overlap” in the position of Taiwan and Cuba as diplomatic pariahs and “Cold War pawns.” But the most important takeaway from the trip was the idea that democratization in Taiwan created a different nation from what had previously existed. The point here is that the Republic of China (ROC), rather than simply being an inconvenient relic of an authoritarian past is (or was) a distinct country from Taiwan.

POSTCOLONIAL BLUEPRINT

Another key idea, says Harrison, is that “we can think about Taiwan in terms of time specifically and through radical political moments through which the word revolution is incredibly analytically substantive and meaningful.”

Hence, a central argument of this book is that “Taiwan’s post-World War II trajectory is [thus] explicable as an instantiation of revolutionary time.” This view holds revolutions to be “interruptive processes” that move towards “unlikely futures” with an “unknown ending date.” Whether these processes culminate in Taiwan’s recognition as an independent nation remains the burning question, but it shouldn’t negate the view of Taiwan’s experience as revolutionary. In fact, “the deep refusal in the international system and its structures of power to see Taiwan as a country or as worthy of nationhood” is tied to a “particular postcolonial national blueprint: armed rebellion, prolonged war, total defeat of the previous government and the declaration of a new nation.”

INDIGENOUS MISSIVE

Analyzing Taiwan through revolutionary time is just one of “four ways of telling Taiwanese history” presented in chapter two. The others are equally instructive. Firstly, the authors examine Taiwan’s history through the lens of indigeneity, noting that the country’s “contested status make its premodern history especially prone to instrumentalization.”

The authors highlight sociologist Mark Munsterhjelm’s argument that Taiwan’s indigenous peoples are “living dead” who are “valued for their genetic and cultural links to pre-Sinophone Taiwan but discriminated against today and made to serve political ends that are not necessarily of their choosing.” The point here — that indigenous aspirations toward land restoration, self-rule and “autonomism,” do not always mesh with the goals of Taiwan independence — is important and frequently misunderstood in treatments of Taiwan’s multiethnic makeup.

Still, China’s threat to Taiwan has “created space to confront, however imperfectly, the legacy of Han settler colonialism,” in a way that is unthinkable across the strait. Furthermore, indigenous voices are increasingly critical of Beijing’s aggression.

An example is the 2019 open letter from representatives of all 16 of Taiwan’s recognized peoples and two plains indigenous groups addressed to China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平). This followed Xi’s demand that Taiwan submit to a purported “one country two systems” arrangement. While the missive expressed dissatisfaction with the ROC government, it emphasized that “Taiwan is a nation we are trying to build together” and that the writers rejected Beijing’s brand of “monoculturalism, unification and hegemony …”

SUBVERSIVE PRACTICE

The so-called “one country, two systems” is further discussed in a section on Taiwan’s past and possible futures in relation to Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong, while Taiwanese identity, which the authors argue is mistakenly depicted as a new phenomenon is another means of understanding Taiwan’s story. This identity is traced back to civil society activism and the home rule movement of the 1920s and 1930s under Japanese colonialism or, less convincingly, to the short-lived Republic of Formosa under Tang Ching-sung (唐景崧), the last Qing governor.

As Chou and Harrison acknowledge, Tang envisioned “self-governance” rather than outright independence and swore fealty to the “eternal Qing” (永清). So their argument that this doomed early attempt to establish a republic “prefigured the articulation of a modern island-wide Taiwanese identity” is controversial and could play into Han-centric depictions of Taiwan’s history. Likewise, the idea that the massacre known as the 228 Incident “marked the start of a decades-long campaign for Taiwanese self-rule” could be misleading, particularly as it comes shortly after the statement that Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) government enforced “the forgetting or outright denial” of the crackdown. Overall, though, this is nitpicking. Packed with elegant analogies, deftly illustrated examples, and subtle but clear, compelling arguments, this book is both educational and immensely enjoyable. The nuanced style mirrors the complex subject matter, and one standout passage makes just such a point: Taiwan’s marginalization, it is argued, “means that seeking to know and understand it is, by definition, a subversive practice.”

Analysis and reporting of Taiwan, thus, “requires standing outside the rules of the international system as the Taiwanese themselves do, and speaking directly about Taiwan as a society, state and even a nation.”

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the