April 21 to April 27

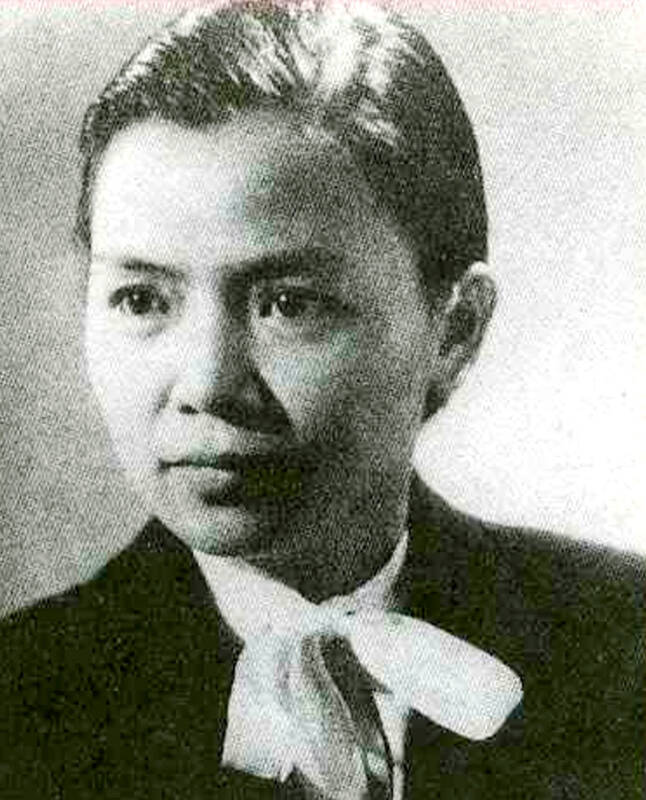

Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she sought to improve women’s welfare and boost participation in politics.

On April 24, 1948, Hsieh was elected Taiwan’s first female legislator, garnering the sixth-highest votes nationwide. She served with her usual enthusiasm and energy at first — but abruptly quit in October 1949, moving to the US and not returning until 1991.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Growing up under Japanese rule, Hsieh was a bright and outspoken student who became Taiwan’s first female surgeon in 1940. She deeply resented colonial rule, and in 1943 she was arrested for plotting to sabotage the Japanese troops and help the Allies take over Taiwan. The authorities offered to release her if she would collaborate with the Japanese on medical work, but she staunchly refused, remaining in jail and subject to torture until the end of World War II.

“As long as I have a drop of blood left, I belong to the Chinese people!” she reportedly said defiantly.

As such, she was happy to work with the KMT, finding herself quite adept at navigating the treacherous world of politics. So why did she leave Taiwan?

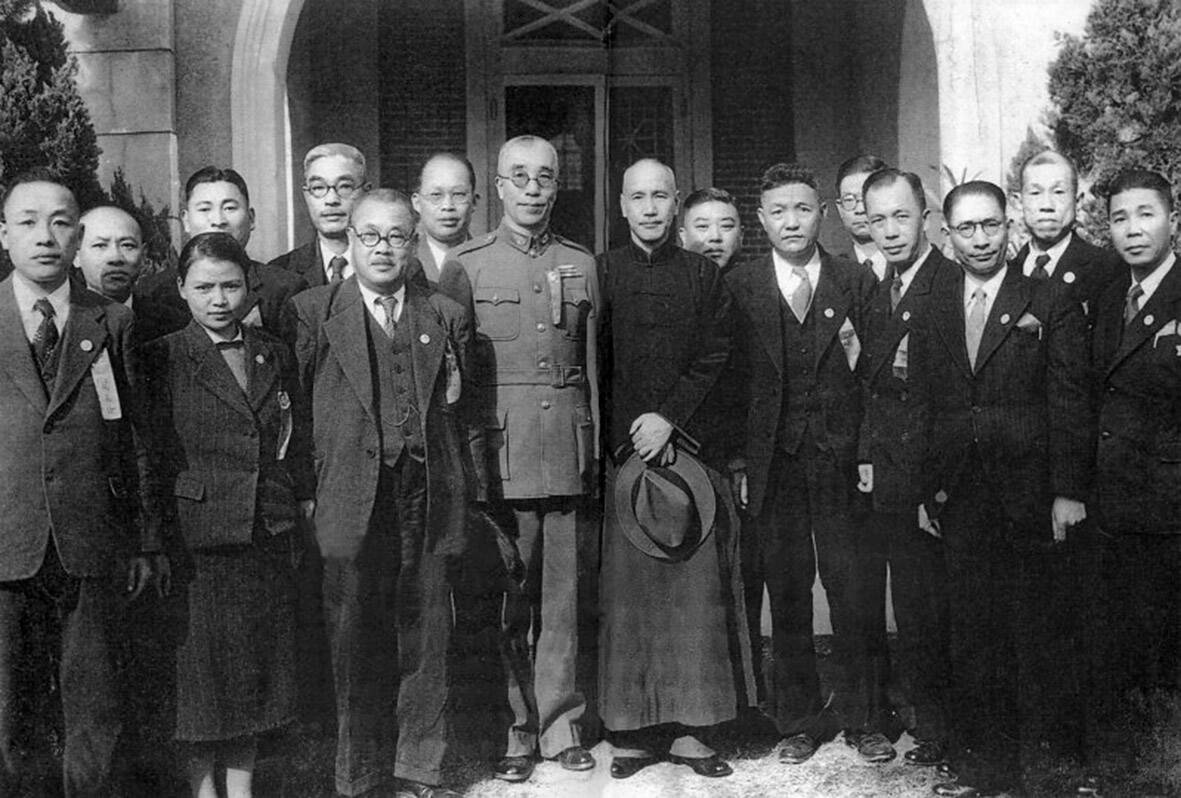

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HEADSTRONG YOUTH

Hsieh was born in January 1918 in Taipei’s Wanhua District (萬華); her father ran a Chinese restaurant next to the Red House in the Ximending area and the family lived a comfortable life.

According to her entry in the National Museum of Taiwan History, Hsieh had a bold personality from a young age. For example, when she saw boys picking on girls in the classroom, she was known to jump onto their desks and confront them.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Due to the influence from her father and uncle, Hsieh saw China as the “motherland” and detested colonial rule, especially after the various injustices she witnessed. Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China two years after she began her medical studies in Tokyo, and she chose to be a surgeon because she hoped to one day join the battlefield and treat wounded Chinese soldiers, writes Lin Chiu-min (林秋敏) in “The rise and the retreat of Hsieh Er on the political stage of Taiwan” (謝娥在臺灣政壇的崛起與退出).

After working in Japan for two years, Hsieh returned home and was hired by Taihoku Imperial University Hospital (today’s National Taiwan University Hospital). It was unheard of for women to perform surgery, and people often gathered outside the operating room’s glass door to get a glimpse of her in action.

In 1943, she and a group of students began discussing plans to thwart the colonial government. They believed that under the Republic of China, they could finally become first-class citizens, Lin writes.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Historica

Thinking that the Allies were planning to land in Taiwan soon, they decided to aid the effort. The plan was to send two delegates to China to meet with the Allies, while the rest would poison Japanese troops and blow up military facilities when the time came. However, the plot was leaked, and Hsieh was jailed in the spring of 1944.

WOMEN’S CHAMPION

Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945, and Hsieh was released in early September. Her father bought a building on today’s Yanping N Road, where she established Kangle Surgical Clinic (康樂外科醫院). She was gregarious and generous, treating those in need for free, and the clinic soon became a gathering space for politicians, businessmen, students and women’s rights activists to discuss current events and their ideals for the new era. Numerous prominent citizens of Taipei passed through her doors, setting the foundation for her political career.

In December, Hsieh joined the KMT. She was active immediately, and in addition to organizing the Taipei Women’s Association and the Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, she served on numerous other male-dominated party committees. Lin writes that Hsieh wasn’t just able to break gender barriers, she crossed factional lines with ease and also had a knack for dealing with the media.

In the opening statement for the first issue of Taiwan Women Monthly (台灣婦女月刊), Hsieh wrote: “Our goal is not to demand power, nor to defeat or challenge men; we just want to be able to fulfill our responsibility in this crucial time of statebuilding and work for the betterment of our country, our people and the world … We ask for our rights so that women have the means to fulfill this duty. We’re not launching a women’s movement just for the sake of a women’s movement.”

She sought to raise women’s status through education and economic autonomy, and hoped to train more women to enter politics. Lin writes that she made solid steps towards these goals during her three years with the women’s associations.

On March 15, 1946, Hsieh was elected as the only female out of 26 Taipei city councilors — beating out 38 candidates in her district. Among other issues, she pushed for equal opportunity and pay for government employees, recruitment and training of female police and the establishment of public birthing centers to reduce birth mortality.

She was one of the most active members during the Constituent Assembly, her boundless energy mentioned in several newspaper reports. One issue she particularly took interest in was establishing minimum quotas for women during elections.

THE COMMUNIST DILEMMA

The 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed by the KMT, broke out the following year. On that day, Hsieh visited Taiwan Garrison Command head Ko Yuan-fen (柯遠芬) and urged him not to fire on the protestors (which happened). She later questioned the officials why there were gunshots and wounded people, and they lied by saying that the troops only fired warning shots into the air and the protesters got hurt in the ensuing stampede.

She believed their words and broadcast the message to the people, urging them to stay calm and that governor Chen Yi (陳儀) would exercise leniency and not prosecute the instigators. This message greatly angered the protesters, and the next day they smashed up her clinic, forcing it to close down.

However, the 228 Incident didn’t affect her popularity during the legislative elections in April 1948. Lin writes that she took on the role with gusto for the first three months, not just working on women’s issues but also tackling diplomacy, public health, finance and other topics.

However, her attendance declined as her term went on, and soon she left Taiwan for the US via France.

Lin writes that after a legislative trip to China, Hsieh saw that the KMT was about to lose the Chinese Civil War. She had already been jailed by the Japanese and had her clinic destroyed, she couldn’t imagine being persecuted by the Communists if they took over Taiwan. At the same time, her association with several Taiwanese who became leftists or communists due to their disappointment in KMT rule led to rumors that she was also one of them. Martial law was declared in May 1949, opening the period of White Terror when anyone could be arrested for being a communist. Faced with pressure on both sides, she decided to flee.

Hsieh received her PhD in public health from Columbia University and worked in the field for decades. She only dared to return to Taiwan after the lifting of martial law, where she spent the last five years of her life.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality