The genetic testing company 23andMe has filed for bankruptcy, prompting people who’ve used the service and sent in DNA samples to be analyzed to wonder what will happen to their genetic data.

The company says the filing does not change how it stores, manages or protects customer data. But some privacy experts are recommending that people who have used 23andMe delete their data, given concerns not only about a potential buyer getting access to sensitive information, but also hackers who might take advantage of the upheaval to gain access to it.

“What we’re witnessing with 23andMe is a stark wake-up call for data privacy,” said Adrianus Warmenhoven, a cybersecurity expert at NordVPN. “Genetic data isn’t just a bit of personal information — it is a blueprint of your entire biological profile. When a company goes under, this personal data is an asset to be sold with potentially far-reaching consequences.”

Photo: AFP

WHAT HAPPENED?

23andMe filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on Sunday. Anne Wojcicki, who co-founded the company nearly two decades ago and has served as its CEO, stepped down effectively immediately. The San Francisco-based company said that it will look to sell “substantially all of its assets” through a court-approved reorganization plan.

Wojcicki’s resignation comes just weeks after a board committee rejected a nonbinding acquisition proposal from her to take the company private.

Wojcicki still intends to bid on 23andMe as the company pursues a sale through the bankruptcy process. In a statement on social media, Wojcicki said that she resigned as CEO to be “in the best position” as an independent bidder.

23andMe says that filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection will help facilitate a sale of the company, meaning that it’s seeking new ownership. The company said it wants to pull back on its real estate footprint and has asked the court to reject lease contracts in San Francisco and Sunnyvale, California and elsewhere to help cut costs. But the company plans to keep operating during the process.

IS MY DNA SAFE?

In a post about the Chapter 11 process, 23andMe said its users’ privacy and data are important considerations in any transaction and that any buyer will be required to comply with applicable laws when it comes to how it treats customer data.

But experts note that laws have limits — for instance, the US has no federal privacy law and only about 20 states do.

There are also security concerns. For instance, the turmoil of a bankruptcy and related job cuts could leave fewer employees to protect customers’ data against hackers. It wouldn’t be the first time — a 2023 data breach exposed the genetic data of nearly 7 million customers at 23andMe, which later agreed to pay US$30 million in cash to settle a class-action lawsuit accusing the company of failing to protect customers whose personal information was exposed.

Experts note that DNA data is particularly sensitive — and thus valuable.

“At a fundamental biological level, this is you and only you,” said David Choffnes, a computer science professor at Northeastern University and executive director of its Cybersecurity and Privacy Institute. “If you have an email address that gets compromised, you can find another email provider and start using a new email address. And you’re pretty much able to move on with your life without problem. And you just can’t do that with your genetic code.”

23andMe says it does not share information with health insurance companies, employers or public databases without users’ consent and with law enforcement only if required by a valid legal process, such as a subpoena. Choffnes said while that’s good, it’s a fairly narrow set of categories.

“There’s still other things that they are allowed to do with that data, including, as they mentioned, provide cross context, behavioral or targeted advertising,” he said. “So, you know, in a sense, even if they aren’t sending your personal data to an advertiser, there’s a long line of research that identifies how third parties can re-identify you from de-identified data by looking for patterns in it. And so if they’re targeting you with advertisements, for example, based on some information that they have about your genetic data, there’s probably a way that other parties could piece together other information they have access to.”

HOW CAN I DELETE MY DATA

California Attorney General Rob Bonta issued an urgent consumer alert Friday — before 23andMe filed for bankruptcy — noting the company’s financial distress and reminding people they have the right to have their data deleted.

If you have a 23andMe account, you can delete your data by logging in and going to “settings” and scrolling to a section called “23andMe Data” at the bottom of the page. Then, click “View,” download it if you want a copy then go to the “Delete Data” section and click “Permanently Delete Data.” 23andMe will email you to confirm and you will need to follow the link in the email to confirm your deletion request.

If you previously asked 23andMe to store your saliva sample and DNA, you can also ask that it be destroyed by going to your account settings and clicking on “Preferences.” And you can withdraw consent to third-party researchers to use your genetic data and sample under “Research and Product Consents.”

The depressing numbers continue to pile up, like casualty lists after a lost battle. This week, after the government announced the 19th straight month of population decline, the Ministry of the Interior said that Taiwan is expected to lose 6.67 million workers in two waves of retirement over the next 15 years. According to the Ministry of Labor (MOL), Taiwan has a workforce of 11.6 million (as of July). The over-15 population was 20.244 million last year. EARLY RETIREMENT Early retirement is going to make these waves a tsunami. According to the Directorate General of Budget Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), the

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

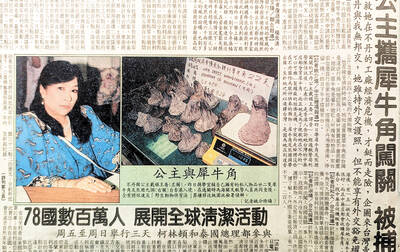

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted