March 16 to March 22

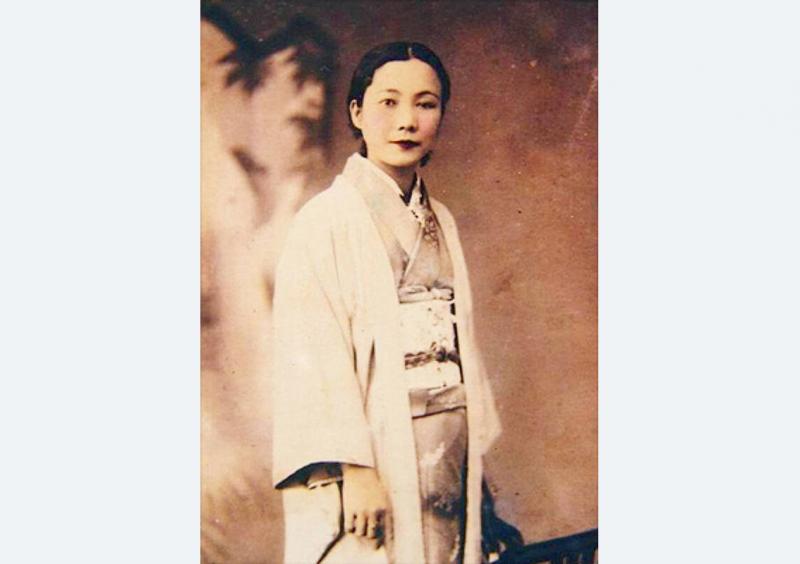

In just a year, Liu Ching-hsiang (劉清香) went from Taiwanese opera performer to arguably Taiwan’s first pop superstar, pumping out hits that captivated the Japanese colony under the moniker Chun-chun (純純).

Last week’s Taiwan in Time explored how the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) theme song for the Chinese silent movie The Peach Girl (桃花泣血記) unexpectedly became the first smash hit after the film’s Taipei premiere in March 1932, in part due to aggressive promotion on the streets.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Seeing an opportunity, Columbia Records’ (affiliated with the US entity) Taiwan director Shojiro Kashino asked Liu, who had been recording opera tunes for the company since 1929, to perform the song as a part of a batch of “pop music” releases under a new stage name, catapulting her to island-wide recognition.

Her popularity soared after she recorded the theme songs for the movies Repentance (懺悔) and A Wise Mother (倡門賢母). Meanwhile, the record company and movie promoters worked together, regularly having Chun-chun perform live at screenings.

As Columbia Records solidified its position as Taiwan’s top hitmaker, Chun-chun was its most prolific artist, her voice appearing on 97 out of 250 recordings made during the 1930s, according to music history researcher Huang Yu-yuan (黃裕元). Many are still instantly recognizable today — but none more than the legendary Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風), which conveyed the conflicting emotions of a young girl yearning to experience her first love.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Unfortunately, her stardom was cut short as the Japanese authorities clamped down on Taiwanese culture and the entertainment industry in 1940 due to World War II. She died three years later at the age of 29, succumbing to tuberculosis that she contracted from her late husband.

OPERATIC BEGINNINGS

Chun-chun was born in 1914, the only daughter of a couple who ran a noodle stand in Taipei, writes Cheng Heng-lung (鄭恆隆) and Kuo Li-chuan (郭麗娟) in Faces of Taiwanese Ballads (台灣歌謠臉譜).

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

Mesmerized by the Taiwanese gezai opera (歌仔戲) shows that were often put on near the stall, she convinced her parents to let her quit school at the age of 13 to join a troupe. She became one of its principal performers in just a few years, garnering a loyal fan base with her good looks and outstanding voice.

Columbia began releasing Taiwanese folk music records in 1926. As gezai opera was the colony’s most popular genre among Han Taiwanese, the company invited Chun-chun’s troupe to the studio in 1929. Two years later, they signed her as a solo artist under her real name Ching-hsiang, and continued their ongoing sonic experimentations by having her croon opera tunes to Western instrumentation. At the age of 16, she traveled to Japan for the first time to record in the studio.

In 1932, she recorded her first batch of pop songs for Columbia as Chun-chun, including The Peach Girl, which made her a household name. Other tracks include a Taiwanese cover of the Japanese enka bestseller Is Sake Tears or Sighs? and the moralistic Quit Whoring (戒嫖歌), but they failed to attract listeners, convincing Kashino that movie songs were the way to go.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

These pop songs followed the characteristic seven-word folk song structure also used in gezai opera, so the transition was quite natural for Chun-chun, writes Huang Wen-ju (黃文車) in “The practical significance from movie theme songs to Taiwanese pop lyrics” (從電影主題曲到台語流行歌詞的實踐意義). At first, she maintained her theatrical, dramatic gezai delivery.

“Her voice was unadorned and bright, and it would crack on occasion … Later, she started to control her enunciation and emotions better, developing a new pop singing style,” the National Museum of Taiwan History writes of her musical evolution.

‘MODERN WOMAN’

In 1933, Kashino went all in on Taiwanese-language pop, tasking employee Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉) with putting together an all-star team. Names still widely recognized today include lyricists Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) and Lin Ching-yueh (林清月), and composers Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), Su Tung (蘇桐) and Yao Tsan-fu (姚讚福). These creators trained Chun-chun and other singers in Columbia’s office in Taipei, cranking out hit after hit.

Lee and Su penned Chun-chun’s next movie theme songs, Repentance and A Wise Mother, solidifying her position as a bona fide star. These two songs still championed traditional morals, but the songwriters soon departed from the seven-character structure and began espousing modern, progressive values in their prose.

For example, Chun-chun sings these lyrics written by Chen in the 1933 Dancing Age (跳舞時代): “I am a modern woman, free to go north, east, south or west ... In this civilized age, we can socialize openly. Men and women pair up and each form a line, I love dancing the foxtrot the most.”

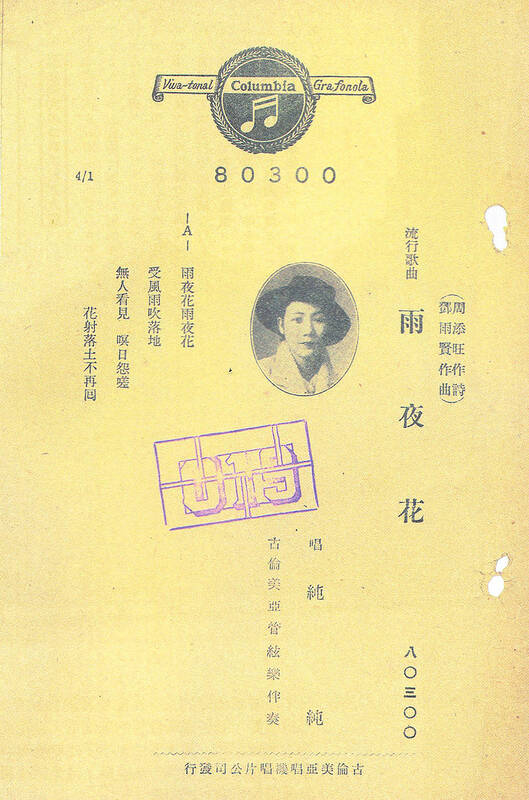

Over the next two years, Teng composed what could arguably be considered Chun-chun’s three most famous songs, still popular today: Moon Night Sorrow (月夜愁), Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風) and Flowers in the Rainy Night (雨夜花).

In 1935, Chun-chun opened a cafe behind Taipei Main Station called “Brazil,” and fell in love with a Taihoku Imperial University (today’s National Taiwan University) student who frequented the shop, Cheng and Kuo write. They planned to get married, but her lover’s family refused to accept a singer and performer as a daughter-in-law, forcing them to break up.

Ironically, Chun-chun’s first hit, The Peach Girl, promoted freedom of marriage and urged parents not to meddle in their children’s love life, warning that doing so could lead to tragedy.

THE MUSIC STOPS

Chun-chun later married a Japanese customer surnamed Shiraishi, who not only was a freeloader, he eventually contracted tuberculosis, which was then a highly contagious and incurable disease. Although she seemed happy in the marriage, clearly discernible through her singing during this period, her friends and family urged her to leave him. Chun-chun refused and insisted on personally caring for him, and soon after he died in 1937, she realized she had also fallen ill.

With the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War that same year, the colonial authorities began restricting the content and production of Taiwanese music. Chun-chun briefly joined Nitto Records, where she continued to collaborate with Teng and Yao, most notably producing Four Seasons of Red (四季紅) as well as the patriotic war songs Sending You Off (送君曲) and Comfort Bag (慰問袋).

As Japan’s imperial ambitions intensified, the government further clamped down on local entertainment and luxury goods in late 1940, and this golden decade of Taiwanese pop music came to a sudden halt. Chun-chun’s final recording, per Shih Ching-an’s (施慶安) “Study on the record industry and Taiwanese pop songs during the Japanese colonial era” (日治時期唱片業與台灣流行歌研究), was Beautiful Spring (美麗春), a duet with fellow diva Ai-ai (愛愛) for Columbia Records.

With no stable work and due to lack of resources during war time, Chun-chun was unable to properly care for her health, quietly passing away in 1943.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,