If South Korea formally impeaches its suspended president over his martial law debacle, one firebrand pastor says he is ready for “revolution.”

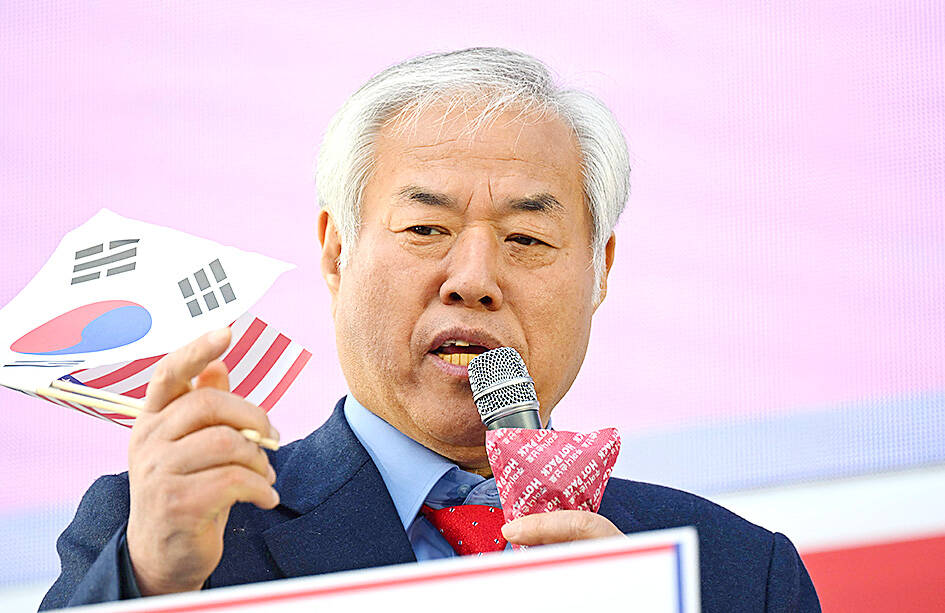

Evangelical preacher Jun Kwang-hoon is one of President Yoon Suk-yeol’s most fervent defenders, calling Yoon’s Dec. 3 martial law declaration a “gift from God.” He has been prepping his followers to take action for weeks, and Yoon’s release from detention over the weekend on procedural grounds has turbo-charged 68-year-old Jun’s sermons.

“If the Constitutional Court decides (to impeach him), we will mobilize the people’s right to resist and blow them away with one blade swoop,” Jun told hundreds of supporters during a service held Sunday outside Yoon’s residence.

Photo: AFP

Authorities are so worried about the potential for violence when the Constitutional Court issues its ruling on Yoon this month that police have been granted special permission to use pepper spray and collapsible batons if his supporters get unruly.

They have cause for concern.

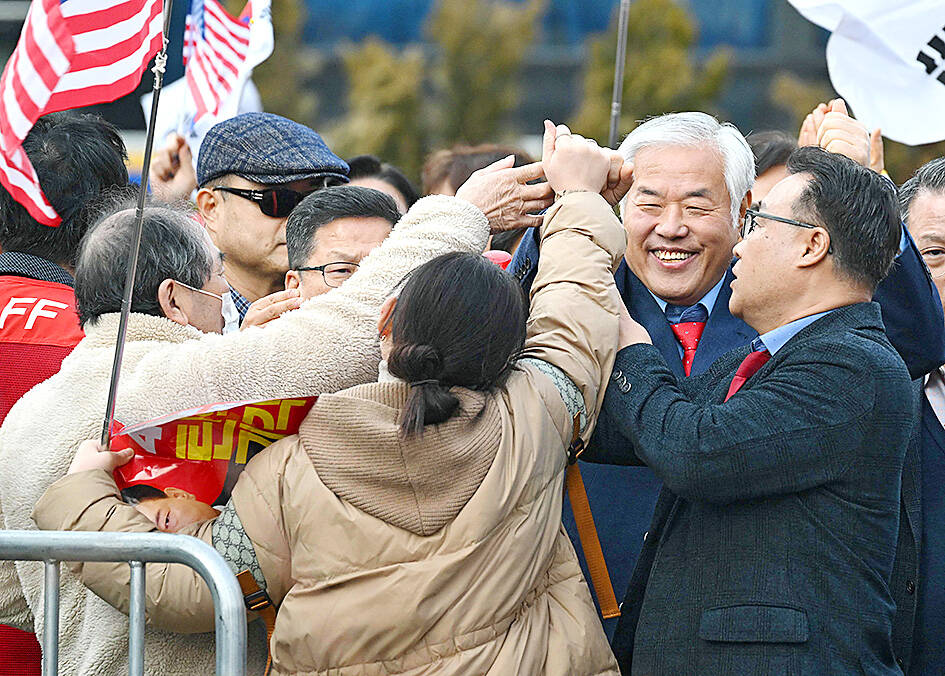

The pastor — long a fringe character on the extreme right edge of South Korean politics — has moved into the mainstream in recent weeks by taking to the streets as the disgraced president’s chief apologist.

Photo: AFP

“President Yoon started the cleansing with his declaration of martial law. The people and I will finish it together,” Jun said Sunday.

He claims North Korea is behind the country’s democratic opposition and has promulgated unfounded claims of widespread election fraud — all echoed by Yoon and his lawyers in their defense of martial law.

Jun is already under police investigation in connection to the storming of a courthouse in January, with two of his followers arrested at the scene.

Police said they will mobilise all resources to avoid a repeat when the Constitutional Court rules.

‘FOUND HIS FLOCK’

Experts say the pastor — best known for defying COVID-gathering limitations during the pandemic — has tapped into a previously marginalized far-right constituency that has expanded in the wake of Yoon’s martial law declaration.

Around a quarter of South Koreans are Christians, and Jun has “found his flock among the elderly underclass of South Korean society,” said Kim Jin-ho, a theologian and analyst.

His audience are “those whose values have been shaped by anti-communism but who have found little resonance in the prosperity gospel of mainstream conservative Protestantism,” Kim said, adding that the pastor has a knack for provocation, much like “an online conspiracy theorist.”

As a result, Jun has raised an unlikely coalition behind Yoon — older Koreans steeped in Cold War ideology and a young, mostly male cohort fluent in an Internet culture scornful of politics.

“Pastor Jun speaks for the people,” said 37-year-old Park Jun-seo Saturday at a pro-Yoon rally.

“He is the only one brave enough to speak truth to power.”

Seo Hui-won, in his 60s, said Jun was “fighting on the frontlines” of a war against communism. If Yoon is formally removed by the court, it would trigger an election in 60 days. As they confront the real possibility of a coming poll, even mainstream conservative politicians are eagerly jumping on Jun’s bandwagon.

Key figures from Yoon’s People Power Party have taken to the stage at Jun’s previous rallies, crediting the pastor and his supporters for creating momentum for a conservative revival.

Their association with the firebrand pastor helps them “gain a base of loyal voters,” said Jeon Sang-jin, a sociology professor at Seoul’s Sogang University. But for the country, this means that the pastor’s conspiracy theories, “once relegated to the fringes, have been legitimized by Yoon, the PPP and the far-right media,” Jeon said.

If upheld by the court, Yoon would become the country’s second president to be formally impeached.

Police are on high alert after riots broke out over the removal of Park Geun-hye from office in 2017.

Experts warn that Yoon — who remains under criminal investigation — appears to be seeking to whip up his hardline supporters.

Yoon had no choice but to “sacrifice himself and declare martial law” to purge the “worms infesting the country’s executive, legislature and judiciary,” lawyer Seok Dong-hyun told the huge crowds at one of the pastor’s protests.

Such rhetoric seems intended to help Yoon retain political influence even if his impeachment is ultimately upheld, said Lim Ji-bong, a constitutional law professor at Sogang University.

“This kind of messaging may provoke his supporters to reject the Constitutional Court’s verdict and incite another violent incident like the courthouse riot last month,” Lim said.

“This will not only undermine the country’s judicial system, but destabilize South Korea’s political foundation at its very core.”

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not