To help meet the cost of moving about 10,000 residents from low-lying homes menaced by rising sea levels and floods, the remote Pacific Ocean nation of Nauru aims to sell citizenships for the climate-threatened island.

President David Adeang is seeking to raise an initial US$65 million for work to transform the barren interior — left as an uninhabitable moonscape by decades of phosphate mining — with a project to ultimately develop a new township, farms and workplaces. Around 90 percent of the population would eventually be relocated under the plan.

Foreigners paying at least US$140,500 for a passport will likely never step foot on the island nation, which lies around 4,000km northeast of Sydney, though can take advantage of visa-free access to destinations including the UK, Singapore and Hong Kong.

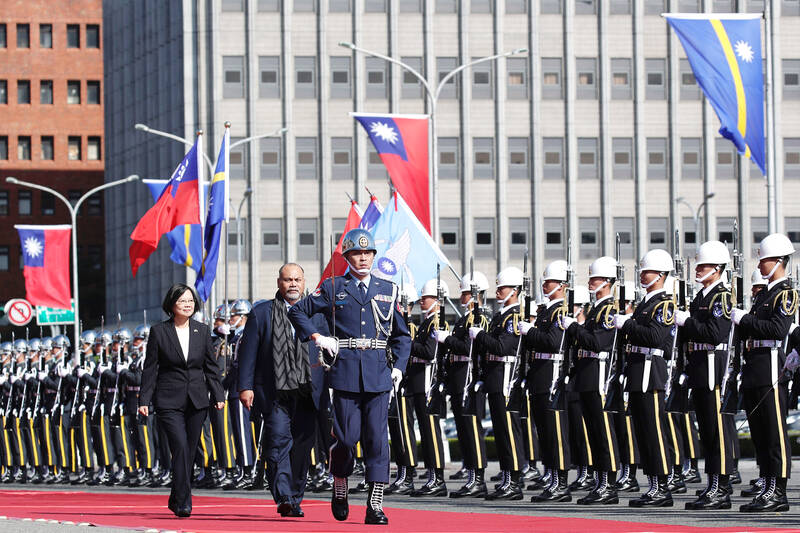

Photo: EPA-EFE

“While the world debates climate action, we must take proactive steps to secure our nation’s future,” Adeang, elected in 2023, said in a written response to questions. “We will not wait for the waves to wash away our homes and infrastructure.”

CLIMATE CHANGE

Nauru follows Dominica in aiming to use proceeds from citizenship sales to protect their populations from escalating impacts of climate change. It’s an illustration of the challenges small nations face in securing funding to deploy on initiatives to boost resilience. While rich economies have increased the rate of loans and grants to developing countries, the gap between available and required adaptation financing could be as much as US$359 billion a year, the UN Environment Program said in a November report.

Photo: AP

Negotiators for a bloc of small island states, including Nauru, at one point abruptly walked out of tense climate finance talks during last year’s COP29 summit in Azerbaijan, and an eventual deal — under which wealthy states pledged to deliver at least US$300 billion in annual support for climate action —fell far short of the more than US$1 trillion a year that had been sought.

Adaptation initiatives “require substantial financial resources which is an ongoing struggle,” Adeang told the UN General Assembly in New York last September. “When it comes to climate finance, we are too often relegated to the back of the queue.”

Between 2008 and 2022, Nauru received US$64 million in development financing that had a principal focus on addressing climate change, according to the Lowy Institute, a foreign affairs think tank.

Nauru faces significant increases in extreme flooding in the coming decades, according to NASA’s Sea Level Change Team. The number of flooding days — when water levels were at least 0.5 meters above a benchmark — totaled 8 between 1975 to 1984, and 146 between 2012 and 2021, the NASA data shows. Already, the estimated annual cost to small island developing states — a group of 39 nations that includes Jamaica and Fiji — from coastal flooding is more than US$1.6 billion a year.

A higher frequency of major floods threatens to overwhelm Nauru’s coastal population centers, government buildings, and the nation’s only airport — with a runway that’s adjacent to the ocean, said Alexei Trundle, associate director (international) at the Melbourne Centre for Cities, and who is helping Nauru develop a vulnerability assessment report.

Passport sales alone won’t fully cover the costs of Nauru’s Higher Ground Initiative, first outlined in 2019, and officials are exploring the potential to also win support from public and private sources. An initial A$102 million (US$65 million) phase is underway to free up about 10 hectares of land on the island’s so-called Topside, which was mined for phosphate — commonly used in fertilizer — for about a century from the early 1900s. Nauru gained independence in 1968.

“Demand for these sorts of programs is not going to go away,” said Kristin Surak, an associate professor of political sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and author of The Golden Passport: Global Mobility for Millionaires.

It means it’s important there’s transparency “in terms of vetting and in terms of flows of money,” she said.

The Lee (李) family migrated to Taiwan in trickles many decades ago. Born in Myanmar, they are ethnically Chinese and their first language is Yunnanese, from China’s Yunnan Province. Today, they run a cozy little restaurant in Taipei’s student stomping ground, near National Taiwan University (NTU), serving up a daily pre-selected menu that pays homage to their blended Yunnan-Burmese heritage, where lemongrass and curry leaves sit beside century egg and pickled woodear mushrooms. Wu Yun (巫雲) is more akin to a family home that has set up tables and chairs and welcomed strangers to cozy up and share a meal

Dec. 8 to Dec. 14 Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.” She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽). While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

President William Lai (賴清德) has proposed a NT$1.25 trillion (US$40 billion) special eight-year budget that intends to bolster Taiwan’s national defense, with a “T-Dome” plan to create “an unassailable Taiwan, safeguarded by innovation and technology” as its centerpiece. This is an interesting test for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and how they handle it will likely provide some answers as to where the party currently stands. Naturally, the Lai administration and his Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are for it, as are the Americans. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is not. The interests and agendas of those three are clear, but