Jan. 20 to Jan. 26

Taipei was in a jubilant, patriotic mood on the morning of Jan. 25, 1954. Flags hung outside shops and residences, people chanted anti-communist slogans and rousing music blared from loudspeakers.

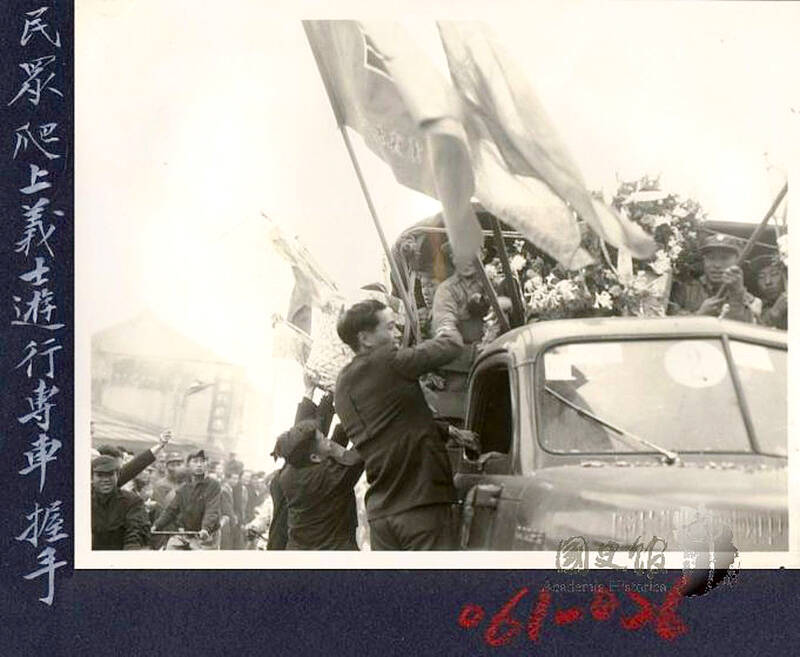

The occasion was the arrival of about 14,000 Chinese prisoners from the Korean War, who had elected to head to Taiwan instead of being repatriated to China. The majority landed in Keelung over three days and were paraded through the capital to great fanfare.

Photo courtesy of Library of Taiwan Historica

Air Force planes dropped colorful flyers, one of which read, “You’re back, you’re finally back. You finally overcame the evil communist bandits and chose the path of freedom, winning for us this political victory …”

While each soldier had their reasons for choosing Taiwan, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) extolled their loyalty and determination to escape the clutches of Beijing, honoring them as “anti-communist heroes” (反共義士). Jan. 23, the day they were released from the POW camp, was designated as “123 Freedom Day.”

The irony, of course, was that it was the height of the White Terror and Taiwan was far from free. Nevertheless, Taiwan’s anti-communist allies all commemorated the occasion, with US president Dwight D Eisenhower writing to the prisoners, “you have our lasting gratitude for your heroic contribution to the cause of liberty.”

Photo courtesy of Library of Taiwan Historica

For the first few decades, grandiose celebrations were put on every Freedom Day, one of the many events the government put on to sustain national fervor and patriotism. But as the political climate changed, the occasion declined in importance.

In 1991, the KMT officially announced that it would no longer try to unify China by force, ending the “communist rebellion.” Two years later, Jan. 23 was officially renamed World Freedom Day to focus on greater global peace.

PRISONERS TO HEROES

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950 when North Korean troops crossed the 38th parallel. On Oct. 19, Chinese “volunteer” troops joined the fray and clashed with the Allied forces supporting South Korea a week later. They engaged in five major battles with the enemy over the next eight months, with about 21,300 taken prisoner, according to Chou Hsiu-huan (周秀環) in “Study on receiving anti-communist heroes from the Korean War ” (接運韓戰反共義士來臺之研究).

Although Taiwan did not participate in the war, it helped the Allied forces by providing agents for psychological warfare and interrogation of Chinese prisoners. Allies also recruited people from Taiwan and Hong Kong to broadcast propaganda, telling Chinese soldiers they could safely surrender, writes Huang Ko-wu (黃克武) in “123 Freedom Day: Examining the rise and fall of Taiwan’s anti-communist legend through a holiday” (一2三自由日 — 從一個節日的演變看當代台灣反共神話的興衰).

Two-thirds of these prisoners were estimated to be former KMT soldiers, and clashes broke out in the camp between pro and anti-communist supporters. Some began agitating to join the KMT in Taiwan instead of being sent back to China. In the end, the Americans allowed them to choose their repatriation destination for “respecting personal choice, increasing the military force of the Republic of China and preventing these people from becoming victims of the Chinese Communist Party after they return,” Chou writes.

Photo courtesy of Library of Taiwan Historica

At first, the media painted them as unfortunate captives from the “bandit” side, but under KMT orders in 1953, the narrative shifted to portray them as defiant heroes whose determination to break free of the communist yoke was to be greatly admired and praised. While there were surely soldiers who made their choice out of patriotism, later interviews revealed that many did it for personal reasons, including fear of retribution if they returned to China — especially those who had anti-communist tattoos.

ONE TWO THREE

In 1953, the government reached out to the Chinese prisoners, and sent two delegations from Taiwan to visit them. Civilian efforts also began in earnest to support them in coming to Taiwan, including nearly 500 organizations. They vowed to do anything to help the prisoners escape the “schemes of the communist bandits and safely reach Free China.”

It became a nationwide effort as donations and gifts poured in; people wept and left passionate messages at a photo exhibition of the prisoners. All supporting groups came together in Taipei on Dec. 23, 1953, and unanimously decided to designate Jan. 23 as “Anti-Communist Hero Freedom Day.”

The main event to welcome them was held at Taipei’s Zhongshan Hall, but celebrations took place all over the nation, including the outlying island of Kinmen, where military bells rang for two hours. Three songs were written for the prisoners that were played on all radio channels: “We sing to welcome the heroes, our passion flows wildly! Flows wildly! Today flesh and blood reunite once more, we will never part again! Never part!”

The popular chant “One two three, let’s go to Taiwan, Taiwan has Alishan, Alishan has a divine tree, next year we’ll return to the mainland” (the lines rhyme in Chinese) was allegedly composed on the fly by a six-year-old boy (although the claim is dubious). Nevertheless, this chant was commonly recited in schools during the 1960s and 1970s.

The Voice of Justice (正義之聲) radio station devised a one-two-three hand gesture that became popular: one, with one’s thumb out, represented freedom, two was the V sign meaning victory, and three signified that the Three Principles of the People was the only way to save China.

Soon, the holiday was referred to simply as 123 Freedom Day.

TOWARD TRUE FREEDOM

The occasion was celebrated with zeal the following year, with freedom bells sounding 23 times simultaneously in Taiwan’s major cities, followed by a plea for those living behind the iron curtain to flee to freedom.

The 1961 movie Fourteen-thousand Witnesses (一萬四千個證人) became the ninth-highest grossing production of the year, Huang writes. The film showed how the prisoners tattooed anti-communist slogans and used their blood to make a Republic of China flag in the camp to show their determination not to return to China. These deeds were also written into the textbooks.

Huang writes that the 123 Freedom Day festivities increased in scale and intensity each year. With the establishment of the Asian People’s Anti-Communist League in 1954, other like-minded governments began observing the occasion as well. In 1966, the league expanded beyond Asia and became the World Anti-Communist League, and at the annual meeting the following year they all agreed to observe Jan. 23 as World Freedom Day.

By 1987, defeating the Chinese communists had become no more than a pipe dream. With the lifting of martial law and other wartime provisions, people turned their focus to more imminent matters. In 1989, politicians called on the public to remember these anti-communist heroes, and while the 123 Freedom Day celebrations continued, public interest waned.

Huang writes that during the 1990s, Freedom Day instead became a rallying point for those advocating for different types of freedom, such as freedom of movement for disabled people and freedom for stray dogs about to be put down in the shelters.

On Jan. 23, 1999, a night club even held a Freedom Day party.

“Half a century later, although [Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石)] did not achieve his goal of ‘reclaiming China and liberating our suffering compatriots,’ fortunately, after shedding its ‘anti-communist’ facade, Jan. 23 had become a genuine day for freedom.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them