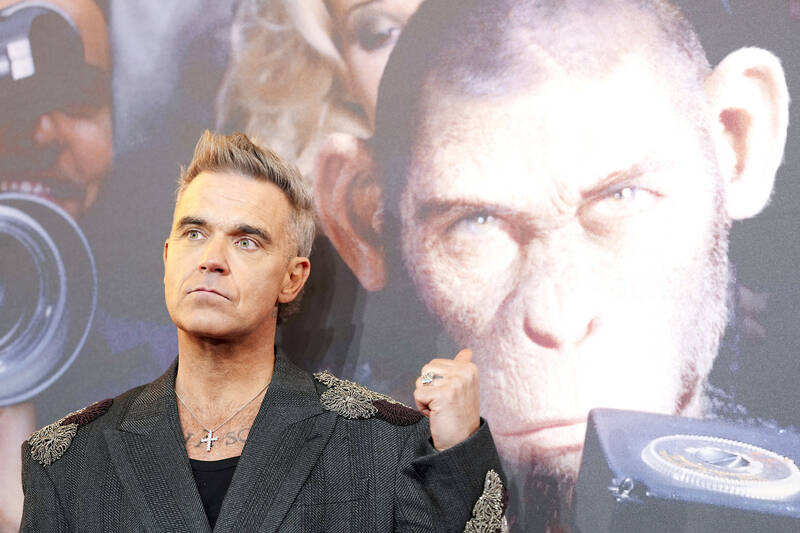

It was a throwaway comment: Robbie Williams, Take That’s cheeky chappie-turned-tabloid fodder solo phenomenon, described himself as a performing monkey, prancing and preening in front of the cameras and seeking the approval of the audience (or at least a banana or two).

But for director Michael Gracey (The Greatest Showman), it was the key to unlocking Williams’s conflicted relationship with his celebrity and his compulsion to perform. In a creative gamble to rival Piece by Piece director Morgan Neville’s decision to tell the Pharell Williams story with Lego animation recently, Gracey replaces Williams in this warts-and-all biopic with a CGI chimpanzee in an otherwise human cast.

It’s a gamble that not only pays off — it’s arguably the main reason the film works as well as it does.

Photo: AP

Narrated by Williams (Jonno Davies delivers a motion-captured performance as Robbie the Monkey) in a tone that strikes a precarious balance between wry self-deprecation and maudlin self-pity, the story itself is pretty generic stuff: a by-the-numbers trawl through the early hardship of Williams’s working-class childhood in Stoke-on-Trent, father-son tensions and industrial-level substance-abuse issues.

The film’s emotional beats — Williams’s doomed relationship with All Saints singer Nicole Appleton; the death of Robbie’s beloved nan — are hammered home with piledriver subtlety.

But the capering ape device transforms what would otherwise be a rote addition to the rock biopic canon, infusing the story with humor, mischief and a sparky, unpredictable anarchy.

Yes, Williams clearly takes himself pretty seriously and has a weakness for therapy-speak platitudes. But he also invites us to see him as a surly adolescent chimp in a shell suit. You have to love him for that.

Better Man is a notable step up for Gracey. The synthetic, rather soulless panache of The Greatest Showman demonstrated his skills as a slick visual stylist, but here he directs from the heart, tapping into the rawness and vulnerability beneath the CGI monkey suit.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

“‘Medicine and civilization’ were two of the main themes that the Japanese colonial government repeatedly used to persuade Taiwanese to accept colonization,” wrote academic Liu Shi-yung (劉士永) in a chapter on public health under the Japanese. The new government led by Goto Shimpei viewed Taiwan and the Taiwanese as unsanitary, sources of infection and disease, in need of a civilized hand. Taiwan’s location in the tropics was emphasized, making it an exotic site distant from Japan, requiring the introduction of modern ideas of governance and disease control. The Japanese made great progress in battling disease. Malaria was reduced. Dengue was