Dec. 30 to Jan. 5

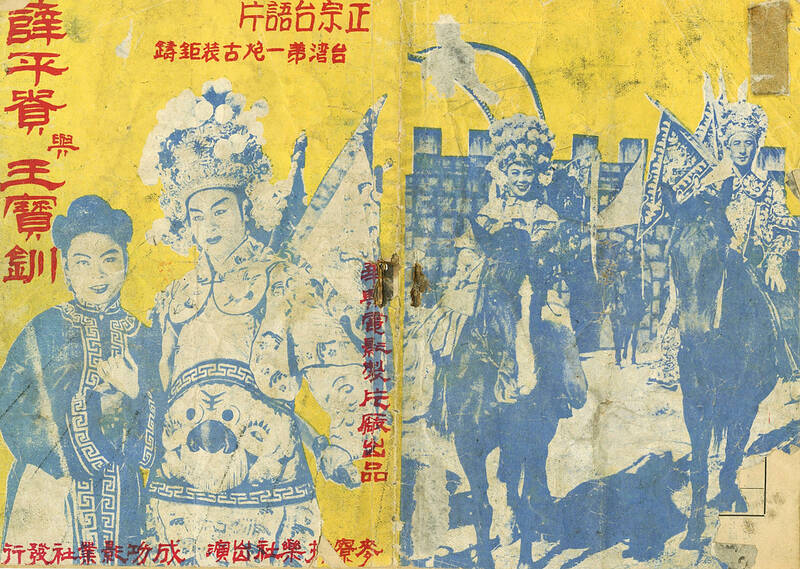

Premiering on Jan. 4, 1956, Xue Pinggui and Wang Baochuan (薛平貴與王寶釧) unexpectedly packed theaters for the next 27 days.

Taiwan’s first 35mm Hoklo-language (commonly known as Taiwanese) movie beat out the top Hollywood blockbuster, Land of the Pharaohs, and the Mandarin-language Peach Blossom River (桃花江) in box office sales, kicking off a craze that lasted until around 1970. More than 800 Hoklo-language films were made despite government attempts to promote Mandarin.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) owned the nation’s three major production houses, mostly creating Mandarin films filled with anti-communist messages and patriotic propaganda. But most Taiwanese could not yet understand Mandarin, preferring traditional opera and puppetry performances as their main source of entertainment.

During the early 1950s, Xiamenese films produced in Hong Kong made their way to Taiwan, and since the language was intelligible to Taiwanese speakers, people began eschewing opera for these films. Dissatisfied with the situation, Japan-educated filmmaker Ho Chi-ming (何基明) teamed up with local opera troupe Mailiao Music Society (麥寮拱樂社) to adapt the classic opera performance Xue Pinggui and Wang Baochuan to the big screen.

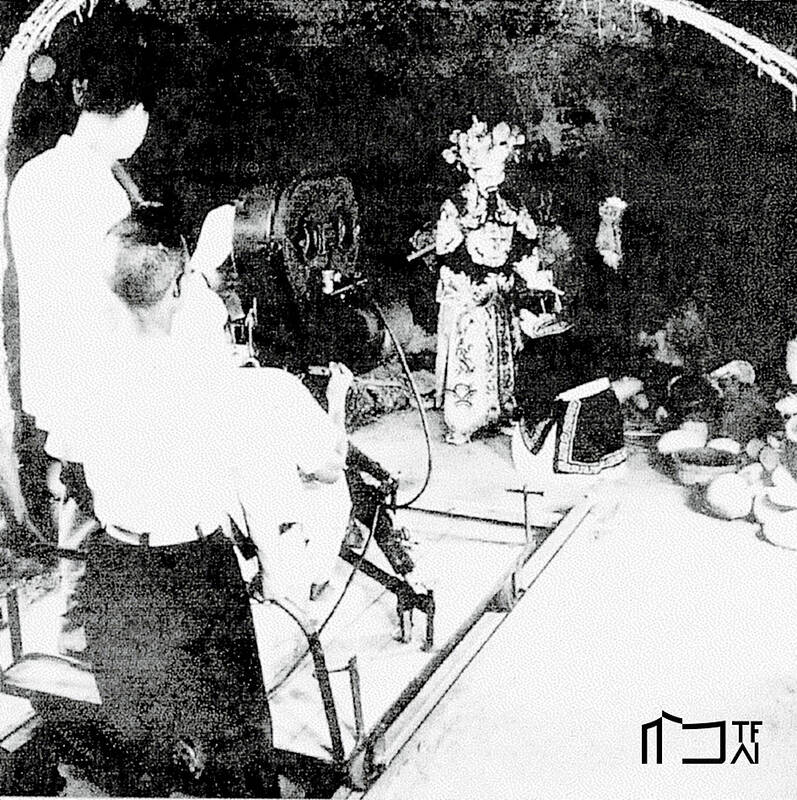

Armed with an Eyemo 100-foot camera and a handful of studio lights, shooting commenced with about 100 performers in a makeshift studio in Nantou County, with none of the actors having any on-screen experience. Critics praised Ho’s tight production and careful attention to detail and aesthetics, and harbored high hopes for the Taiwanese-language movie scene that was soon to blow up.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

INSPIRING DUD

Xue Pinggui and Wang Baochuan was not actually the first Taiwanese-language feature film; that honor belongs to the 16mm Romance of the Western Chamber (六才子西廂記), which premiered at Taipei’s Daguan Theater (大觀戲院) on June 13, 1955. The filmmaker was Shao Lo-hui (邵羅輝), an opera troupe director who was frustrated that people would rather see the Xiamenese films than his performances.

The film was completed in one month, with most of the shooting happening immediately after the troupe’s stage performances so the actors could stay in costume. The poor production and image quality made it a total flop, and it was axed after three days.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

A United Daily News editorial slammed Romance of the Western Chamber as “worthless,” noting that “there was no artificial lighting, no montages, the editing was abrupt … Not only did the entire film feel clunky and unnatural, due to a lack of lighting it was difficult to even see the actors’ faces.”

“However, although the film failed, it inspired countless others to try their hand at the craft, since the method they employed was a lot easier and less time consuming than that of the major film studios,” it concluded. “It was a strong boost of confidence to aspiring filmmakers.”

One of these aspirants was Ho Chi-ming. Ho was born in 1917 to a wealthy landowning family in Taichung. His uncle had a 9.5mm film projector, and from a young age Ho was fascinated by how the images shown brought much joy to the villagers.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

At the age of 16, Ho headed to Japan to study medicine, but after touring a film studio, he decided to devote himself to the artform. He trained at the Konishi Professional School of Photography (today’s Tokyo Polytechnic University) and honed his craft at a professional studio after graduation. According to the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute (TFAI), he was the first Taiwanese to study filmmaking in Japan.

Ho later returned to Taichung and worked for the prefectural government, showing movies at local schools and organizations, and producing “social guidance films” that he traveled across the colony to screen.

HOPEFUL REVIEWS

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

After the war, Ho continued making documentaries for the Taichung County Government, highlighting public works, local industry and official policy. In 1950, he launched Huaxing Movie Production Company (華興製片廠), the first privately-owned studio in Taiwan, and made 16mm documentaries, promotional videos and special effects sequences that were inserted into traditional opera performances for scenes that could not be performed on stage, such as people falling off a steep cliff.

His younger brother Ho Ling-ming (何錂明), who also became a filmmaker under his influence, joined the company in 1952. The duo were well-known in the opera scene, and in 1955 Mailiao Music Society owner Cheng Cheng-san (陳澄三) approached them for a collaboration.

Filming of Xue Pinggui and Wang Baochuan began in August 1955, with the younger Ho serving as cinematographer. Set during the Tang Dynasty, the classic folk tale depicted a love story between an ordinary soldier and a princess, and how they overcame an 18-year separation when the soldier was taken hostage by an enemy kingdom.

The United Daily News criticized the lack of creativity in the film as it was mostly a wholesale adaptation of the opera performance to the big screen, but they were excited for the potential of a thriving Taiwanese-language movie industry.

Fellow director and film critic Pai Ko (白克) was more forgiving: “Although we cannot measure this film with overly high artistic standards, there are many bright spots ... Even though the stage performers had no experience, they gave maximum effort. It’s also evident that the director put a lot of thought and care into the production, making use of natural wind, and employing beautiful camera angles. The transitions between scenes are natural and vivid, breaking from that of traditional opera. Although the set was unspectacular due to resource constraints, the team employed clever, well-designed techniques to build up the atmosphere.”

Pai noted that while in opera, females often play the role of younger male leads, it did not work for a movie as the soldier appeared too feminine. He added that the Taiwanese folk song Diu Diu Deng (丟丟銅仔) seemed out of place in a movie set in ancient China.

“Nevertheless, the appearance of a film solely using local resources and manpower is extremely exciting,” he concluded. “If they can go beyond Taiwanese opera and move on to historical dramas and even modern stories, then there is definitely a bright future for Taiwan-produced Taiwanese-language films.”

EXPANSION AND FALL

The film’s success led to a flurry of new studios and movies; 1957 saw the release of 62 Taiwanese-language films, reaching a peak of 120 in 1962. A United Daily News editorial from Nov. 13, 1956 notes, “it’s been just over a year since the first Taiwanese-language film appeared, but it’s already one of the most competitive and lucrative businesses.”

Ho built a 400 meters squared studio in 1956, which could contain six sets plus an outdoor filming area. A sequel to Xue Pinggui and Wang Baochuan was soon released, as well as now-classics such as Green Mountain Bloodshed (青山碧血), the first film to depict the 1930 Wushe Incident (霧社事件) where the indigenous Seediq rose up against colonial oppression, and The Canal Suicides (運河殉情記), also based on true events.

In 1958, Ho visited Japan and brought back a slew of cutting-edge equipment. Huaxing made eight films that year, including another film about the anti-Japanese resistance, The Bloody Tapani Incident (血戰?吧哖). They also took on three commissions by outside directors.

However, Huaxing ran into financial difficulties after this and stopped producing original material, although the studio was rented out to other companies. The most famous is arguably the 1959 Brother Wang and Brother Liu Tour Taiwan (王哥柳哥遊台灣), one of the first Taiwanese films that boasted an original story as opposed to dramatizing an existing folk tale or historic event. The comedic duo is considered the local version of Laurel and Hardy, spawning seven sequels. Nevertheless, the studio closed in 1961.

Over the years, the Taiwanese-language movie industry became plagued by shoddy production, as companies churned out films as fast as they could to make a quick buck. Coupled with the government’s vigorous support of the Mandarin-language movie industry, the popularity of Hong Kong cinema and lifting of the ban on Japanese films in 1965, the scene crashed as fast as it rose.

According to TFAI: “Ho Chi-ming’s rigorous, meticulous attitude from his Japanese education and insistence on aesthetic quality was starkly different from the Taiwanese-language films that were hastily cranked out in the industry’s later years.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of