Gabriel Gatehouse only got back from Florida a few minutes ago. His wheeled suitcase is still in the hallway of his London home. He was out there covering the US election for Channel 4 News and has had very little sleep, he says, but you’d never guess it from his twinkle-eyed sprightliness. His original plan was to try to get into Donald Trump’s election party at Mar-a-Lago, he tells me as he makes us each an espresso, but his contact told him to forget it; it was full, “and you don’t blag your way in when the guy’s survived two assassination attempts.”

So instead, Gatehouse headed to Little Havana in Miami, which has a sizeable Cuban American population. No Republican nominee has won Miami-Dade county since 1988, but “the swing to Trump was very visible,” he says. “I saw nothing but joy and happiness, and [the election] hadn’t been called for Trump at that point, but they could kind of sense it, they could feel the momentum, and they were right.”

For months, Gatehouse had also had that feeling — that Trump was going to win. But then prophesying turbulent times ahead has almost become Gatehouse’s brand: his BBC podcast series, and the new book adapted from it, are called The Coming Storm. For the past four years, Gatehouse has been going down a whole warren of rabbit holes, investigating, surveying and seeking to explain the tangled web of conspiracy theories that got the US to where it is now. His journey goes far and wide, from QAnon and the 6 January Capitol riot, to online disinformation networks, artificial intelligence and the libertarians of Silicon Valley, and further back to the buried roots of modern conspiracy theorism: the New Deal in the 30s, the Clintons in the 90s, even a prophetic book co-authored by Jacob Rees-Mogg’s dad, more of which later.

Photo: Reuters

In terms of this election, Gatehouse suggests two factors why Trump won. The first and most obvious, speaking to the Cuban Americans in Little Havana, was the cost of living. “A lot of them told me, ‘My grocery bills have gone up exponentially.’ It’s not clear to me what policies Donald Trump offers that will solve that, but it’s quite clear that this is a problem the Democrats haven’t adequately addressed.”

PRO-SYSTEM VS ANTI-SYSTEM

For the other reason, he points to the New York Times Siena College poll of likely voters in late October. Its top line was that Trump and Harris were neck and neck in the race, but somewhere near the bottom came the question: “Which comes closest to your view about the political and economic system in America?” Only 3 percent thought the system was working fine and 38 percent thought it needed “minor changes”, but 51 percent thought the system needed “major changes” and 7 percent thought that “the system needs to be torn down entirely.”

Photo: AFP

“So you’ve got a nearly 60 percent block who are like, ‘The system sucks, it’s fucked,’ and Trump is attracting those voters. Because, for better or for worse — well, for worse, actually — the Democrats have kind of become the party that defends the system.”

The terms “left” and “right” no longer apply in US politics, he says. “I frame it as pro-system and anti-system.”

This is what unites the coalition around Trump, from the ostensibly Democratic anti-vaxxer Robert F Kennedy Jr, to the anti-“legacy news” crusader Elon Musk, to edgelord manosphere podcasters and wealthy politicians smashing it to “the elites” — they’re the anti-system option. This is also where conspiracy theory comes in, says Gatehouse: “Conspiracy theories are, by definition, anti-system.”

Gatehouse’s attitude to conspiracy theories is “you don’t take them literally, but you take them seriously,” he says. “A conspiracy theory tells you something about society, and the fact that so many Americans believe that the people they elect are not really in charge: hidden hands pulling the strings behind the scenes, all this kind of meta, QAnon stuff about elite cabals. It’s telling you the same thing as that Siena College poll was telling you: belief in the system is catastrophically draining away. And Trump is the guy who promises to rip it all apart, to tear it up, to ‘make America great again.’”

None of this is to say that Gatehouse ascribes to the conspiracist mindset. In contrast to the outlandish and paranoid narratives it lays out, The Coming Storm is level-headed, even-handed and well researched — albeit augmented with a few stirring musical cues, including Gatehouse’s own piano-playing.

Q-ANON

It was almost exactly four years ago — Phoenix, Arizona, in the aftermath of the 2020 election — that he fell down his first rabbit hole.

“It was COVID. I’d missed the election because my visa had run out,” he said.

The state and the election had been called for Joe Biden but he managed to convince his editors that he needed to go to the US nonetheless — to report on the Stop the Steal protest outside the vote-counting center in Maricopa county, which supported Trump’s baseless allegations that the election was rigged against him.

“There are maybe 100 or so people there, colorful characters as ever in America: men with guns; families with babies; and this guy, bare-chested, horns on his head, draped in furs, with a sign that says ‘Q sent me.’”

This was Jacob Chansley, soon to achieve global notoriety as “the QAnon Shaman” — the enduring symbol of the storming of the Capitol building.

“I had vaguely heard about QAnon, but it was really not on my radar at all,” Gatehouse says. He spoke to Chansley — “he was very friendly” — and listened incredulously to his yarn about an anonymous government official, code-named “Q,” revealing on Internet chatrooms that Trump was about to vanquish a cabal of satanic pedophiles led by Hillary Clinton.

Two months later, Gatehouse was back at the BBC headquarters in London, putting together a report on the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, “and suddenly all the TV screens in the whole building are on the US Capitol. There’s a mob storming it. And then we cut inside the Senate chamber, and there he is, my friend with the horns and the furs.”

He kicked himself for not having recorded an interview with Chansley back in Arizona, “but then also I realized that actually this kind of crazy conspiracy theory that I’d dismissed as too niche to put in a serious news program was actually quite important.”

Over the course of two seasons of The Coming Storm, Gatehouse and his producer, Lucy Proctor, investigate the dynamics of modern-day, information-age conspiracy theorism: where it came from, how it is manufactured and how it has fed into mainstream politics. Fredrick Brennan, the creator of 8chan, the message board where the QAnon conspiracy first took hold, told him: “Look for who was using Q and what they were trying to do with it,” says Gatehouse.

“So that led me to look at the people in the Trump orbit, before and after QAnon arrived.”

It also led him back to the US politics of the early Internet era.

CONNECTING THE DOTS

“Names that popped up in the 90s that were pushing conspiracy theories about the Clintons would then pop up again in connection to pushing Q-adjacent conspiracy theories around the stolen election, etc. So then this is what you do as a journalist. You make a connection, right?”

He ended up making a lot of connections, and weaving together a grand and somewhat terrifying narrative of misfits, misinformation and manipulation.

Did he literally map out the grand plot at any stage? With red string on a pinboard, for example?

“I did at one point. But there was so much of it — I mapped out bits of it,” he says, “in an A4 notepad with, like, spider diagrams. Basically, I have these pencils that are black on one end and red on the other. So I was sort of scribbling with my black-and-red pencil.”

Gatehouse is well aware of the pitfalls of such a seductively satisfying exercise.

“At what point are you being an investigative journalist, and at what point are you tipping over into conspiracy theory?”

To be certain, he sent his spider diagrams to Timothy Tangherlini, a professor of folklore at the University of California, who had created an AI machine-learning program that he claimed could tell the difference between a conspiracy theory and an actual conspiracy.

“Because, of course, conspiracies do exist, right? And so I sent him my theory, kind of hoping that he would say, ‘You need to step back from the rabbit hole, my friend.’”

But instead, to his surprise, Tangherlini told him to keep digging.

The parallels between media reporting and conspiracy theory manufacturing are uncomfortably close, especially now that “the media” is itself fragmented into different camps, each pushing its own conflicting version of reality.

“If some people take this series as a sort of critique of establishment media, then we’ll be happy about that,” he says.

Bias is unavoidable: “You’re not just putting facts in there in a random order; you are crafting a narrative, so obviously you are choosing what to include and what to leave out.”

As a conspiracist, you can be more cavalier, but as a journalist, “You’ve got to do that in as honest a way as possible, but you can’t help but go into a story with some kind of preconceived idea of what the story is.”

Gatehouse does come close to positing a conspiracy theory of his own in The Coming Storm, and it’s a terrifying one. It stems from a book called The Sovereign Individual, written in 1997 by the American investor James Dale Davidson and the former Times editor William Rees-Mogg. The book is uncannily prescient about the emerging Internet age: cryptocurrency, disinformation, nationalism, the gig economy and wealthy individuals free from the authority (and tax laws) of nation states. Their vision of the future, says Gatehouse, is “a post-nation-state world in which a few individuals — sovereign individuals — have become so powerful that they rival the gods of Greek myth.”

Certain sections of big tech saw the book almost as a route map; it was reprinted in 2020 with a new preface by the billionaire venture capitalist Peter Thiel.

“He was definitely at the center of one of my spider diagrams,” says Gatehouse.

THE COMING ACCELERATION

Thiel was an early investor in the likes of Facebook, PayPal, the data analysis company Palantir and OpenAI, among others, which connects him to Mark Zuckerberg, Sam Altman and Elon Musk. He has already helped set up a proto-“network state:” an autonomous economic zone called Prospera, on the Honduran island of Roatan. Thiel also has connections with Trump-world: US vice-president elect JD Vance was a protege.

Thiel and Musk could be described as “accelerationist” in their thinking, which means they are keen to speed up the pace of technological change and get to the next level, or planet, or whatever — regardless of the consequences. Where some see climate breakdown, civil disorder and societal collapse as disasters, they see opportunity. All of which leads Gatehouse to ask: “Are big tech billionaires using the Maga movement as a vehicle for their accelerationist cause?”

He follows a lot of people from this community online, he says.

“They were jumping up and down with glee on the night of the election.”

He reads me a line from one of their posts: “Techno kings about to rule the free world. Massive wave of acceleration incoming.”

The coming storm indeed. But not even Gatehouse is making predictions about what a second Trump presidency might bring.

“We just don’t know what’s around the corner,” he says. “My children are six and two. When they’re my age — I am 47 — are they still going to be living under the same system of government and societal structures that I grew up in, and my parents grew up in and, to an extent, my grandparents grew up in? I think that’s an open question.”

Is he optimistic?

“My glass is pretty half-empty at this point,” he admits. “I have an optimistic disposition generally, so I kind of feel like what will be, will be, but I think there’s going to be big changes coming down the track. And some of it might be good. The current system is definitely not perfect, right? There are lots of problems. Is the solution to tear it all down and build it up again from scratch? I think not.”

But tearing things down, being “anti-system,” looks to be on the agenda, between the accelerationists, Musk’s “government efficiency” ambitions and the notorious Project 2025 agenda, which, among other things, includes dismantling key departments such as education and homeland security.

“I don’t know whether Trump has the temperament to build new institutions. I suspect not.”

There is plenty of material for more installments of The Coming Storm, it seems, but Gatehouse is done with this world, he says.

“I need to give my brain a break from conspiracy theories. It does drive you a little bit nuts.”

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

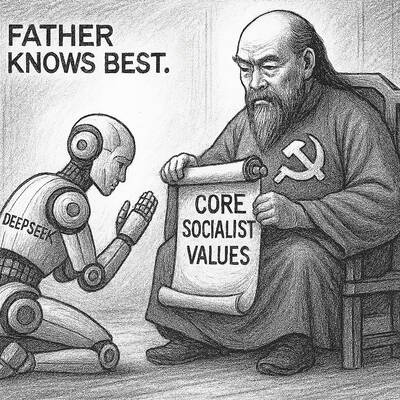

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions

It was Christmas Eve 2024 and 19-year-old Chloe Cheung was lying in bed at home in Leeds when she found out the Chinese authorities had put a bounty on her head. As she scrolled through Instagram looking at festive songs, a stream of messages from old school friends started coming into her phone. Look at the news, they told her. Media outlets across east Asia were reporting that Cheung, who had just finished her A-levels, had been declared a threat to national security by officials in Hong Kong. There was an offer of HK$1m (NT$3.81 million) to anyone who could assist