When I started to read Rachel Shabi’s new book, I felt a profound sense of relief and recognition. As she writes: “The left has ceded the space on antisemitism… and the right has smartly and strategically filled that void.”

As someone who has been involved for years with various causes where leftwing people gather, I wholeheartedly concur. It’s more than time to take back that space. The downplaying of antisemitism by the left has led to some racism being given a free pass, and it has also resulted in a depressing lack of empathy around the Jewish experience and a weakening of potential solidarity.

It has been hard to talk about this for a long time, for fear of detracting from what feels like more pressing anti-black racism. But now, when charges of antisemitism are being used by defenders of Israel to head off criticism of horrific crimes against Palestinians, it often feels pretty much impossible. Still, not dealing with it is not doing anyone except racists any favours, and many of us will feel grateful to Shabi for stepping out into this maze.

While the book is subtitled The Truth About Antisemitism, it quickly becomes clear — if we didn’t already know — that there is no simple truth here, but rather a host of interconnected and complex stories. Shabi, who was born in Israel to Iraqi Jewish parents, and whose previous book explored the experiences of Israeli Jews from Arab countries, is a good and careful guide through many of these thorny paths.

She is sharp on the ways that antisemitism differs from other kinds of racism, and how that can make it difficult to confront. Our paradigm of racism is so often that it targets “people of color in order to subjugate, segregate, colonize, enslave and kill them,” and we expect it to be baked into political and social structures in myriad instances of inequality. Antisemitism does always not fit into that model, not least, as Shabi says, because Jews, by and large, in most places today “don’t face that kind of structural racism.” As other writers have also pointed out, this makes Jews both white and not white — as the title has it: Off-White— depending on the situation.

But antisemitism can be as harmful as any other racism, and spawned the genocide whose trauma still echoes down the generations. Shabi is honest that, while she doesn’t personally share this sense of trauma, she recognizes that for many Jewish people it is still present, and the assumption that they should see themselves as “white” “can flatten out the sense of paper-thin conditionality that feels ever-present for many Jewish people.”

As a Jew brought up in a family still dealing with the ghosts of the past, I would agree that leftwingers need to do better at accepting this all-too-real sense of vulnerability, “without dismissal, disbelief or bad faith.” For sure, the Holocaust is currently being weaponized to head off criticism of Israel, but we don’t get past that simply by denying the reality of Jewish anguish. As Shabi says at one point: “There has rarely been a more urgent need for us to stretch our compassion, to hold Jewish trauma even while a savagely catastrophic war is inflicted on Palestinians in its name.”

The horror of the Holocaust also needs to be recognized in order to understand Israel’s founding, which is not just a simple tale of colonialism. Shabi quotes Edward Said saying “the Palestinians are the victims of the victims, the refugees of the refugees.” Recognizing the complexity of Israel’s past and present means that “decolonization cannot involve drawing up rigid lists of the indigenous and the colonizers.”

This may seem obvious, but Shabi’s reminder to readers that Jewish life and Palestinian life must be treated as equivalent is, sadly, a necessary counterbalance to those on the left who seem to believe that massacring civilians in a gruesome attack can on some level be justified when those people are Israeli Jews.

Another part of the book that I found particularly valuable is its exploration of the way the right is using antisemitism now. I’ve found it really disconcerting to see xenophobic rightwing commentators in Britain suggesting that Jews should make common cause with the far right against Muslims. Are Jews meant to be grateful that at some point we got promoted from being the darkest stain on western civilization to its frontline defenders? It’s good to see that phenomenon explored along with the mad fringe of Christian Zionism, and the bizarre friendships that Israel is trying to make with some of the worst authoritarian governments in the world.

What’s even more disconcerting than the newfound friendship between some Jews and the right is the growth of crazy conspiracy theories that build on old antisemitic patterns of the super-powerful Jew. It’s vital that we are ready to call out and bring into the light these conspiracy theories, which often center on the “great replacement” — the idea that Jews are trying to orchestrate the replacement of white people through immigration — and are becoming frighteningly widespread.

I ended the book invigorated by Shabi’s engaged clarity, and would have liked even more. For instance, I would have been interested in more discussion of antisemitism in Muslim communities. Having traveled in Saudi Arabia and Iran, I’ve been struck by the shocking antisemitism that I’ve encountered, which can go way beyond anti-Zionism.

Muslims in Europe also tend to hold more antisemitic attitudes than the population as a whole. It may be true, as Shabi suggests, that antisemitism across the Middle East has been imported from western traditions of racism, now fanned by western support for Israel, but it would still be useful to have more discussions about how this is playing out in Muslim communities and what can be done to challenge it.

As Shabi herself says, this book is not intended to be the end of this discussion, but a vital part of those overdue conversations that are needed in order to build greater solidarity in this time of crisis. We need to be more confident in separating justified criticism of Israel from antisemitism, and this timely and valuable book should help to build that confidence. Because her key message is a vital one — that the fight against antisemitism is an essential part of the fight against all injustice and dehumanization.

With one week left until election day, the drama is high in the race for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair. The race is still potentially wide open between the three frontrunners. The most accurate poll is done by Apollo Survey & Research Co (艾普羅民調公司), which was conducted a week and a half ago with two-thirds of the respondents party members, who are the only ones eligible to vote. For details on the candidates, check the Oct. 4 edition of this column, “A look at the KMT chair candidates” on page 12. The popular frontrunner was 56-year-old Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文)

“How China Threatens to Force Taiwan Into a Total Blackout” screamed a Wall Street Journal (WSJ) headline last week, yet another of the endless clickbait examples of the energy threat via blockade that doesn’t exist. Since the headline is recycled, I will recycle the rebuttal: once industrial power demand collapses (there’s a blockade so trade is gone, remember?) “a handful of shops and factories could run for months on coal and renewables, as Ko Yun-ling (柯昀伶) and Chao Chia-wei (趙家緯) pointed out in a piece at Taiwan Insight earlier this year.” Sadly, the existence of these facts will not stop the

Oct. 13 to Oct. 19 When ordered to resign from her teaching position in June 1928 due to her husband’s anti-colonial activities, Lin Shih-hao (林氏好) refused to back down. The next day, she still showed up at Tainan Second Preschool, where she was warned that she would be fired if she didn’t comply. Lin continued to ignore the orders and was eventually let go without severance — even losing her pay for that month. Rather than despairing, she found a non-government job and even joined her husband Lu Ping-ting’s (盧丙丁) non-violent resistance and labor rights movements. When the government’s 1931 crackdown

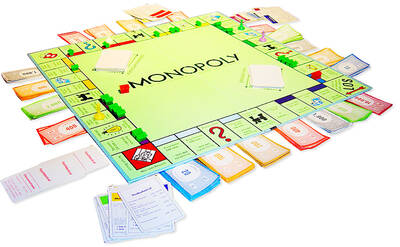

The first Monopoly set I ever owned was the one everyone had — the classic edition with Mr Monopoly on the box. I bought it as a souvenir on holiday in my 30s. Twenty-five years later, I’ve got thousands of boxes stacked away in a warehouse, four Guinness World Records and have made several TV appearances. When Guinness visited my warehouse last year, they spent a whole day counting my collection. By the end, they confirmed I had 4,379 different sets. That was the fourth time I’d broken the record. There are many variants of Monopoly, and countries and businesses are constantly