The first Monopoly set I ever owned was the one everyone had — the classic edition with Mr Monopoly on the box. I bought it as a souvenir on holiday in my 30s. Twenty-five years later, I’ve got thousands of boxes stacked away in a warehouse, four Guinness World Records and have made several TV appearances.

When Guinness visited my warehouse last year, they spent a whole day counting my collection. By the end, they confirmed I had 4,379 different sets. That was the fourth time I’d broken the record.

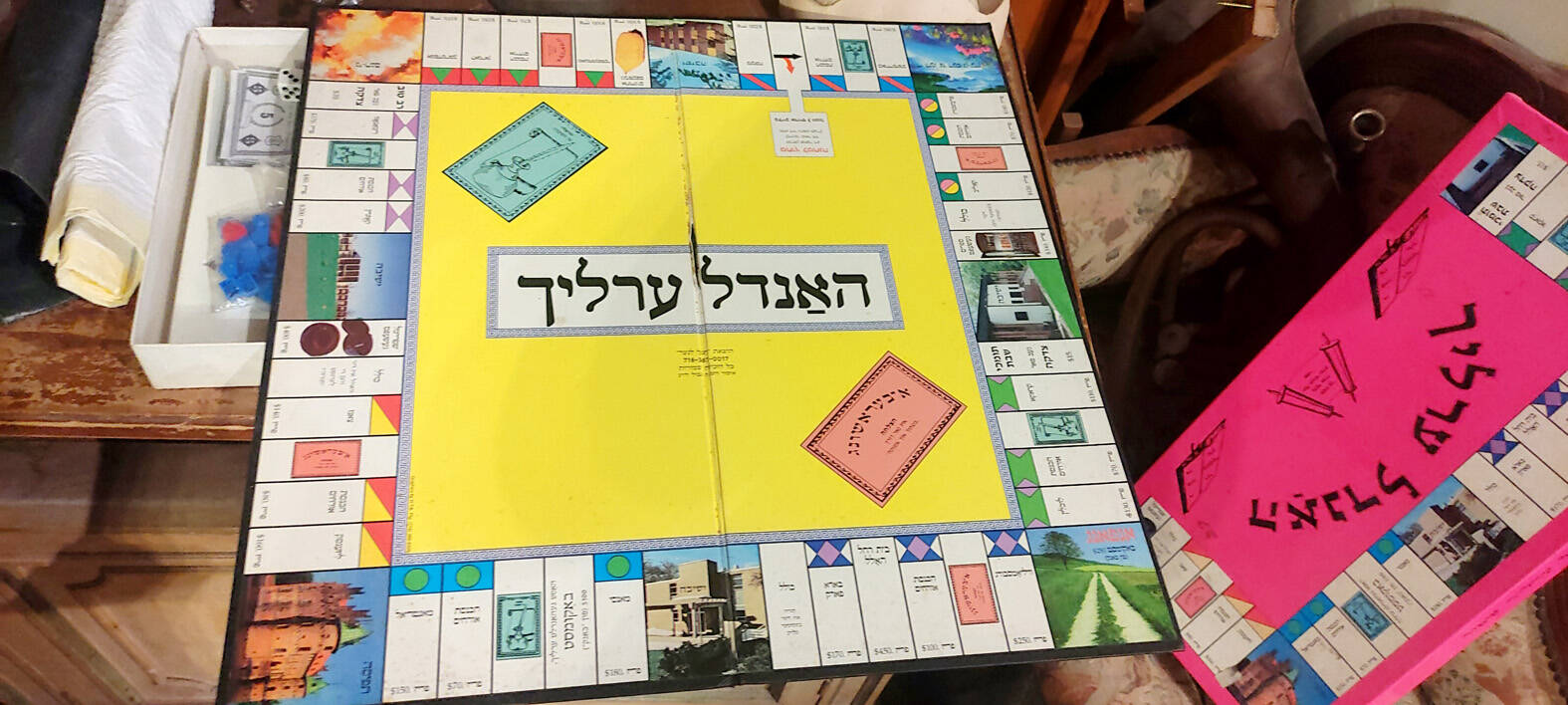

There are many variants of Monopoly, and countries and businesses are constantly releasing their own versions. For me, it’s about the chase, finding the rare ones: a special anniversary edition, a limited production run, or just something incredibly hard to find. I’ve even got the Park Hyatt Sydney hotel edition, which you can usually get only if you stay the night there. I managed to track down a guest online, who bought it for me.

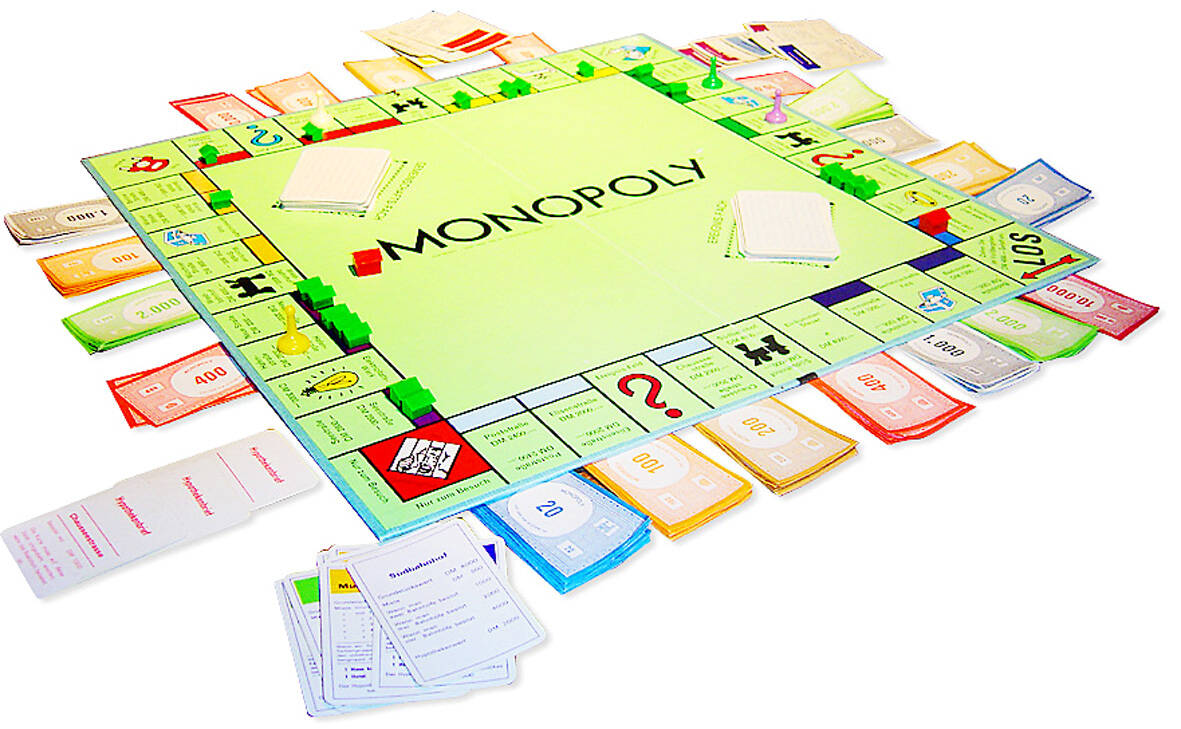

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

I’ve probably spent about £400,000 (US$534,150) on my collection over the years. I’ve been lucky to have a job at DHL for more than three decades, which has helped me keep up with my hobby. The most expensive set I own is a silver edition from London, which would have been worth £2,500 brand new — it was limited edition and used real silver. Luckily, I found mine much cheaper on eBay.

To me, the fun in Monopoly isn’t really in playing it. Once you open the box, you lose about 90 percent of its value. I keep nearly all my sets sealed. If I had a flashy Rolls-Royce, I wouldn’t drive it through the mud — that’s how I see my collection.

People think it’s mad — my girlfriend especially. She gets wound up because the sets take up space and cost money. But I couldn’t give them up. People often ask me: why Monopoly? Why not postcards or stamps? I think it’s because Monopoly is so recognizable.

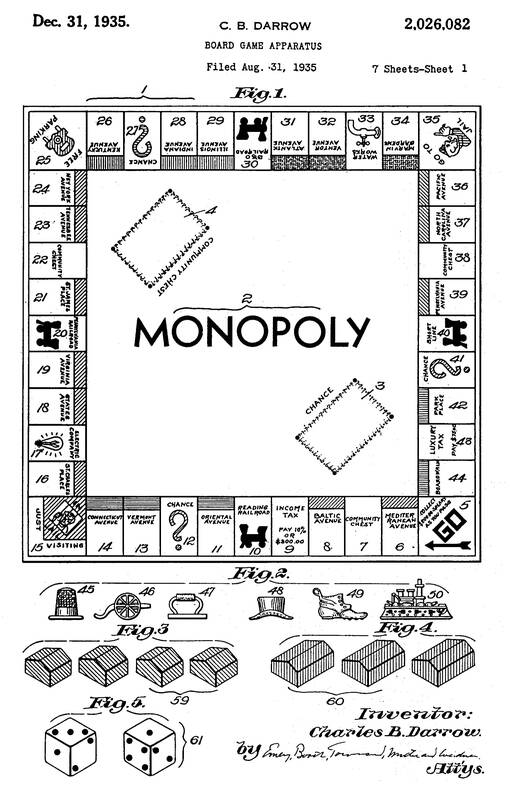

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The hunt is a huge part of the fun. In the early days, I would scour car-boot sales. I began in 2000 and, back then, finding a set meant rummaging through boxes at a market or secondhand shop. The Internet opened up a whole new world. I’ve bought sets from Japan, Brazil and the US. Sometimes I’ll spend months tracking down a rare edition. I wonder if I’m keeping the Post Office, Evri and Amazon running. Of course, storage is a challenge. I live in London, but have rented out a warehouse in Ashford, Middlesex, to keep them all.

People assume I never play Monopoly, but I’m always up for a game. It doesn’t take away from the collecting. In fact, it reminds me why I started in the first place. I’ve met so many wonderful people through the game: other collectors; friends I used to outbid on eBay; the man who runs World of Monopoly, an online archive. People who have heard about my collection have got in touch and offered to bring me a set. Some of them have even flown to the UK from abroad. We’ll take pictures together with the new set and my Guinness World Records certificate, and sometimes even spending the day sightseeing in London. It’s surreal, but it’s brilliant.

I’ve also been on TV shows, such as Bargain Hunt, and radio stations around the world, and visited the factory where the game is made. The record has brought me so many opportunities and friendships I’d never have imagined when I bought that first box.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Right now, I’m after the Twycross zoo set, and in the US there’s a 90th edition of the game with only 600 copies made. That would be nice to get but, really, every set is exciting. The dream is to hit 4,500, maybe even 5,000. But the big milestone will be Monopoly’s 100th anniversary in 2035 — the board game was designed by Elizabeth Magie as The Landlord’s Game in 1903, though it was first commercially released in 1935. Maybe someone will give me a big space in the city to show off the collection. That would be something.

Until then, I’ll keep hunting. There’s always another set out there — a zoo edition, a special anniversary, another release that hardly anyone knows about. If I could go back to my very first set, would I start collecting all over again? I absolutely would.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only