Forty years on from its 1984 release, Bronski Beat’s new wave hit Smalltown Boy has transcended generations to become an LGBTQ anthem for young and old alike.

Narrowly spared the censor’s axe in a Britain where being gay was only partially decriminalized, its tale of coming out and fleeing home has found a new lease of life with a younger audience on social media platforms including TikTok.

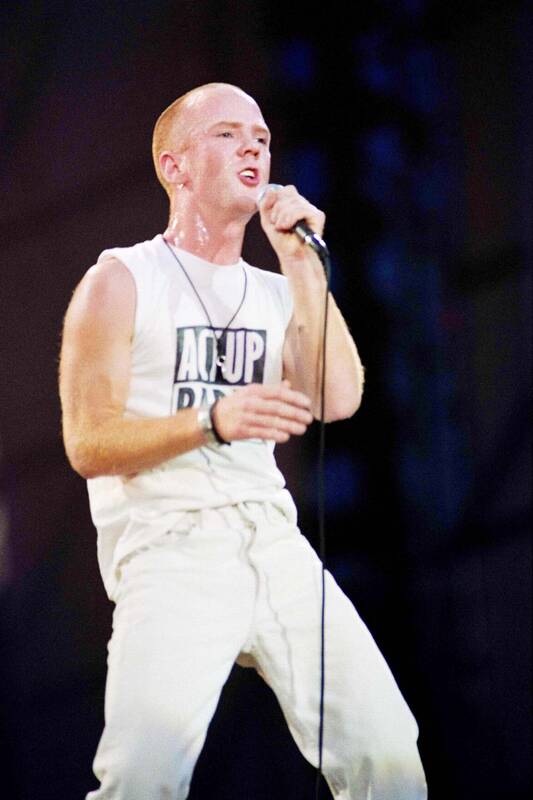

Released on the band’s debut album The Age of Consent, its synth and echoed drum-driven groove rode the wave of popularity with a public increasingly hungry for the “Hi-NRG” electronic disco trend. Charismatic Scottish frontman Jimmy Somerville, later of The Communards, and his plaintive countertenor voice did the rest.

Photo: AFP

Bronski Beat’s label London Records knew they had a surefire hit on their hands as soon as they turned to the UK capital’s iconic LGBTQ club Heaven, famous for its long-running G-A-Y night, to promote the single.

“Suddenly, as we were playing the record, you could see the dance floor get quieter, you know, as people were actually listening to the words,” said the label’s former chief Colin Bell.

“And then the DJ did something, which he says to this day that he’s never done before: he played the record and then he played it again, straight after,” Bell added.

“And that was the moment we knew it was something special.”

COMPROMISE AND OBSCENITY

But to launch the nascent band to stardom, London Records had to walk on eggshells to make sure the hit could air on radio and its iconic music video pass on television.

Same-sex relations were in part decriminalized in England and Wales by the Sexual Offenses Act 1967 — later extended to Scotland in 1980 and Northern Ireland in 1982. But the age of consent — which gave Bronski Beat’s debut album its title — remained 21 years old for gay lovers, compared to 16 years for their heterosexual counterparts. And the same year Smalltown Boy came out, Frankie Goes to Hollywood saw their own gay club banger Relax banned from the BBC’s airwaves on the grounds it was deemed obscene.

But convincing Bronski Beat to compromise proved easier said than done.

“We would ask them to moderate some of the things that they had to do in order to get the records on the radio or on the TV,” Bell said. “There was some tension in the creative relationship we had,” but “we compromised, we softened it and successfully,” he added.

Over the song’s insistent upbeat tempo, Somerville weaves a mournful tale of a boy who has to escape the clutches of parenthood to assert his own identity, however painful that may be: “Run away, turn away,” is the refrain.

Yet the ex-label head underlined that its lyrics and accompanying music video are open to other, more varied interpretations.

“It didn’t stand just for a gay boy being beaten up and taken back to his parents,” Bell said.

“That could be a woman, that could be a girl, that could be anybody.”

TRANSCENDS ALL DIVIDES

With 122 million views on YouTube, Smalltown Boy is experiencing a resurgence in popularity on social media.

On TikTok, the song has trended as the focus of a challenge where users play the 1984 hit and ask their parents to dance like it is the 80s again.

Patrick Thevenin, a journalist of LGBTQ music and culture, said he was “quite astonished by the support for Smalltown Boy, whether gay or straight, by all generations.”

“It’s a classic of gay emancipation and coming out, but its strength lies in the fact that it transcends all divides of gender and sexuality.”

The record has “long since transcended the gay sphere,” Thevenin said.

Even if homophobic attacks and LGBTQ acts persist today, the journalist said he took that as proof that “society is progressing.”

In 2017, a remix of Smalltown Boy by Arnaud Rebotini brought the song to a new generation in France after it was included on the soundtrack for Robin Campillo’s film 120 Battements par minute about AIDS activism, which won the Grand Prix at Cannes.

Three events are planned in London tomorrow to celebrate the album’s 40th anniversary, with marches and concerts by LGBTQ artists at the Queen Elizabeth Hall.

Somerville, long a recluse from the media spotlight, is not expected to attend.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she