Vincent van Gogh’s maverick talent has put him at the center of European culture for more than a century. His works make headlines when they sell, from the record-breaking moment his Irises went for £27 million (US$35.9 million) at Sotheby’s in 1987, right up to this month’s predicted hoopla in Hong Kong, where Christie’s are to auction his riverside scene, Moored Boats, painted two years earlier, for an estimated US$30 million to US$50 million — likely to set a record for works from his later, Parisian period.

The Dutch artist’s dramatic renderings of simple things — plants, trees, furniture and faces — are international emblems of the way we value art. So much so that London’s National Gallery’s renowned 1888 sunflower painting was deliberately targeted last year by Just Stop Oil climate activists, who lobbed the contents of a soup tin at it.

The yellow flowers, happily protected by glass, bloom on regardless and this weekend take up their rightful place alongside two other Van Goghs: a portrait of a mother figure, La Berceuse, and another 1889 vase of sunflowers, lent by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The painter had always intended them to be shown together and now, courtesy of the National Gallery’s new bumper show, Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers, they are reunited for the first time since they were created in the artist’s studio in southern France. This time though, as Van Gogh expert Martin Bailey points out, they appear in “fancy frames.”

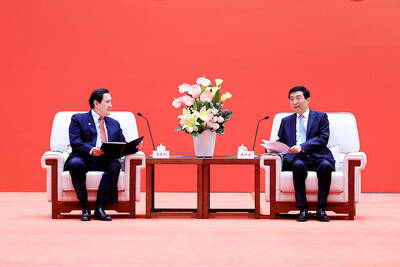

Photo: AFP

“The curators have done fantastically well to get all these loans, which include major masterpieces, such as The Bedroom and The Yellow House. They will have had to fight for every single one,” says Bailey, who blogs for the Art Newspaper.

“Exhibitions often take things chronologically, following an artist’s development, but here the paintings from Arles and from Van Gogh’s time in a nearby asylum at Saint-Remy are mixed together.

“They want us to focus on the painting and to put the myths to one side.”

Photo: AP

The show, marking both 200 years of the National Gallery and 100 years since the arrival of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, opens to the public pre-labeled a “blockbuster’” the sort of must-see attraction museum directors dream of. It is also a term with a few unfortunate connotations, including the taint of safe commercial thinking.

But guest curator Cornelia Homburg, a renowned Van Gogh specialist, is confidently armored against this criticism. She is clear about the purpose of the show, which features 61 spectacular works, including some of the most revered and rarely, if ever, loaned.

“We want to show the artist rather than the tortured soul,” she says. “Of course, our interest is intensified by what we understand of his difficult life.”

Homburg concedes there is some relationship between Van Gogh’s suffering and his art, but stresses they are not the same thing. The key justification for the “blockbuster” she has been working on with Christopher Riopelle since early 2019 is its “solid premise.”

“We needed an angle that means something,” she says, “and the time Van Gogh spent in the south of France is the moment of creative maturity when he really thought about how to be a modern artist.”

So the exhibition challenges what we know, but not what we love about the painter. It updates the common idea that he was unappreciated in his time and that he strove, almost therapeutically, to express his troubled psyche on canvas.

As Homburg points out, while it is certainly true the artist was both poor and mentally ill, he did enjoy the respect of other artists and clung to a strong faith in his future audience.

“He thought about his public and the impact he would have. Everything was deliberate and planned,” she says.

“He knew he might not be widely understood in his day but believed that in 100 years he would be. He changed what he saw when he painted to make it more expressive, but not to express his own feelings. It was totally intentional.”

So if we sense trauma and melancholy in his twisted grove of olive trees trunks, or in a swirling skyscape, then it is because Van Gogh wanted us to, Homburg argues, and not because he felt that way himself.

Bailey agrees: “It is tempting to read meanings into the paintings but it is a mistake. There are a few from the asylum where you could say you see the effect of a mental struggle. This show has deliberately avoided those paintings.”

The gallery’s chosen title, Poets and Lovers, refers to the cast of characters and changing backdrops Van Gogh creates, playing with color to alter real faces and landscapes. Visitors first encounter two portraits, one of a dashing uniformed lover, and then one of a poet, imagined from the face of a painter friend, and bedecked with the firmament of stars that represent dreams for Van Gogh.

In the original painting of the artist’s bedroom in Arles, both these portraits can be spotted hanging above his bed. But in a second version, the one on display in London, Van Gogh romantically supplants these works with the 1889 Self-portrait, also in the show, and a painting of a mystery woman.

Later in the show, visitors meet a less familiar member of the Van Gogh dramatis personae in the 1888 Portrait of a Peasant, which reinvents an old gardener as a rural archetype. The work has never before been loaned to a UK institution by the Norton Simon Collection in Pasadena.

This is a show that leaves the clear impression that Van Gogh was always talking to his public — and even entertaining them.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping

There is an old British curse, “may you live in interesting times,” passed off as ancient Chinese wisdom to make it sound more exotic and profound. We are living in interesting times. From US President Donald Trump’s decision on American tariffs, to how the recalls will play out, to uncertainty about how events are evolving in China, we can do nothing more than wait with bated breath. At the cusp of potentially momentous change, it is a good time to take stock of the current state of Taiwan’s political parties. As things stand, all three major parties are struggling. For our examination of the