Sept.16 to Sept. 22

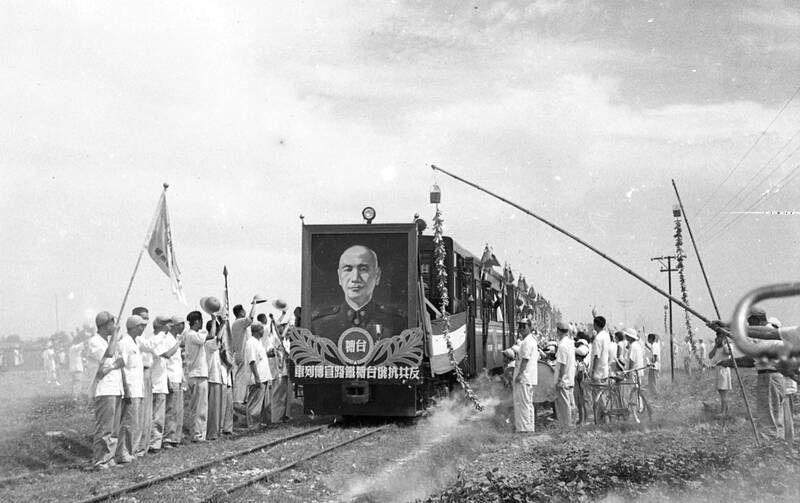

The “anti-communist train” with then-president Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) face plastered on the engine puffed along the “sugar railway” (糖業鐵路) in May 1955, drawing enthusiastic crowds at 103 stops covering nearly 1,200km. An estimated 1.58 million spectators were treated to propaganda films, plays and received free sugar products.

By this time, the state-run Taiwan Sugar Corporation (台糖, Taisugar) had managed to connect the previously separate east-west lines established by Japanese-era sugar factories, allowing the anti-communist train to travel easily from Taichung to Pingtung’s Donggang Township (東港).

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Sugar Corporation Group

Last Sunday’s feature (Taiwan in Time: The sugar express) covered the inauguration of the sugar railway on Sept. 15, 1907 through the end of the Japanese era, when nearly 3,000km of tracks formed a tree-like network in central and southern Taiwan. The miniature trains were nicknamed “half cars” (五分車), referring either to their diminutive size, or them running at half the speed of regular trains.

These railways greatly improved transportation to previously remote areas and had a lasting impact on Taiwan’s rural development. The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) consolidated sugar production under Taisugar in 1946 and set about repairing the tracks damaged by US airstrikes during World War II and expanding the network, and ridership reached its peak in the late 1950s.

The sugar railway remained a mainstay of society until the 1970s, when usage sharply declined due to the improvement of rural roads and the completion of the first national freeway. The last passenger line closed in 1981, and today only one industry line remains active.

Photo courtesy of Lo Yi-chia

CONNECTING THE LINES

By the end of the Japanese era in 1945, the sugar industry was made up of numerous companies, dominated by the “big four” of Dainippon, Taiwan, Meiji and Ensuiko. The factories all had their own sugar railroads that linked up to the Western Trunk Line, and were of varying specification and did not connect to each other, writes Chang Kun-chen (張崑振) in a Newsletter of Taiwan Studies (台灣學通訊) article.

As only eight factories remained untouched by the US bombs dropped during World War II, the new government launched a five-year plan to revive the industry. Part of this included unifying and reorganizing the sugar railway. Things moved along slowly, but after the KMT’s retreat to Taiwan in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, the Ministry of National Defense ordered Taisugar to speed up progress and expand the railroad for potential military use.

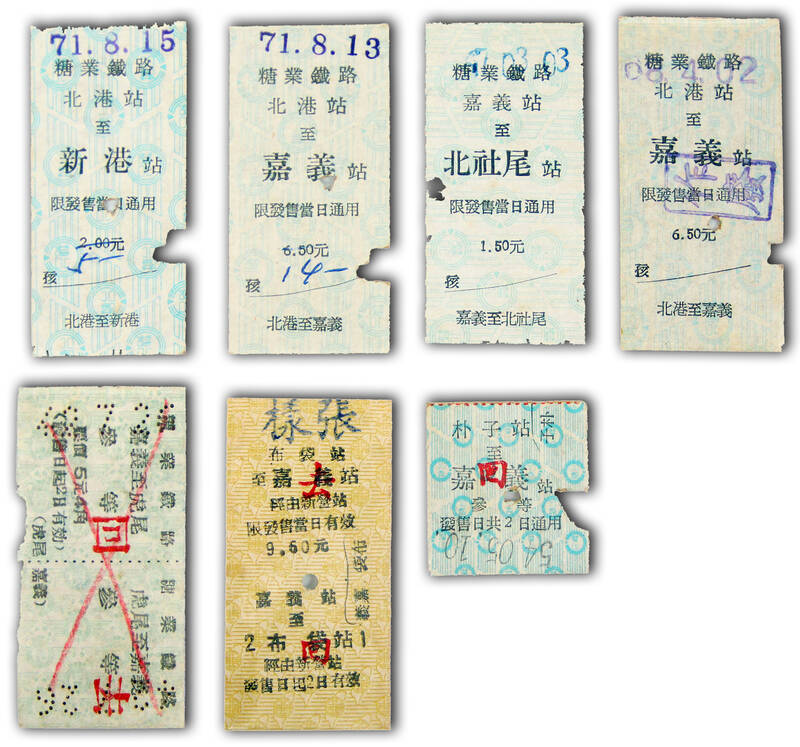

Photo courtesy of Hsinchu City Cultural Affairs Bureau Ticcets

At first, the plan was to build a north-south line from Miaoli to Pingtung, but the authorities found it too costly to build a bridge across the Dajia River (大甲溪), so the northern terminus was set south of the river in Taichung. This 262.2km line was a massive undertaking that included building new bridges and roads, replacing tracks and reinforcing existing bridges and setting up telephone poles and water stops. The southern terminus was Lizihnei Station (籬仔內) in Kaohsiung, although a branch line from Fengshan (鳳山) continued on to Pingtung.

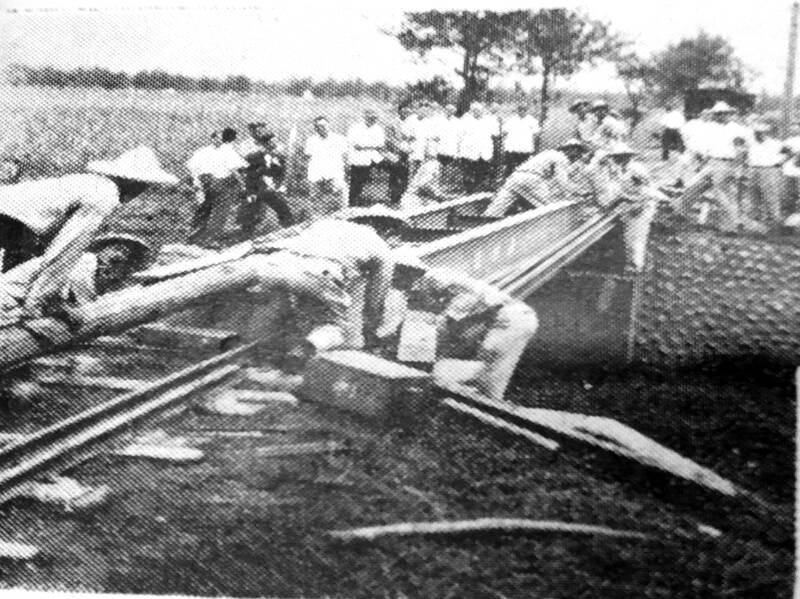

Construction was completed in 1953 with the opening of the Siluo Bridge (西螺) crossing the Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪). The first test run was made on April 25, 1953 with 87 participants on board. The entire run took 11 hours and 24 minutes, with a 15 minute delay due to a minor derailing.

The section between Sijhou (溪州) station in Changhua County and Huwei (虎尾) station in Yunlin County was open to passenger and commercial freight service. Although the north-south line was built with national security objectives in mind, it brought many economic benefits. In fact, it never saw any military use.

Photo courtesy of National Changhua Life Arts Center

RAPID DECLINE

The anti-communist train was quite a spectacle, as riders beat gongs and drums while chanting “oppose communism, resist the Soviets” as it trudged its way through the fields at no more than 20km per hour. The venture not only served to promote patriotism and the national cause of retaking China, but also extolled the benefits of growing sugarcane.

The deadly floods of Aug. 7, 1959 caused irreparable damage to the north-south line in the worst-hit Changhua area, forcing Taisugar to relocate the northern terminus to Ershui Station (二水) and shortening the line by 20 percent. In 1968, the Nantou Sugar Factory closed down, rendering Ershui Station nonfunctional, and in 1974 the northernmost stop was moved north to Yuanlin (員林).

In 1979, the Siluo Bridge was expanded as road traffic increased. The Highway Bureau deemed it dangerous to have the sugar railroad and cars share the same bridge, and thus the entire section north of Yunlin County was abolished, cutting a further 50km from the line.

It was all downhill from here for the sugar railway, which had already been losing money since the late 1960s. Besides slow train transport becoming obsolete, Taiwan’s sugar exports, once a pillar of the economy, also declined. The east-west lines started shutting down one by one, with the Beigang (北港) line — once immensely popular with pilgrims visiting the town’s famous Chaotian Temple (朝天宮) — taking the sugar railway’s final passengers in August 1981.

Meanwhile, the north-south line kept getting shorter. By 1994, it was only operational between Tainan’s Chiali (佳里) and Kaohsiung’s Ciaotou (橋頭) — the station where the first tracks were laid down in 1907. In 1998, with the permission of the Ministry of National Defense, the entire line shut down.

Today, only the 16km-long Magongtsu (馬公厝) line remains, transporting sugarcane from four farms in Yunlin County to Huwei Sugar Factory. Lin Shih-hsiang (林仕祥) writes in an Global Views Monthly article published in April that this line supplies about half the total sugarcane for the factory and conveniently connects the factory’s fields and other facilities.

Plus, with the rapid urbanization of Huwei, switching to road transportation would greatly hamper local traffic during the busy season. Under these conditions, the once mighty sugar railway lives on in this tiny section.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.