Despite her well-paying tech job, Li Daijing didn’t hesitate when her cousin asked for help running a restaurant in Mexico City. She packed up and left China for the Mexican capital last year, with dreams of a new adventure.

The 30-year-old woman from Chengdu, the Sichuan provincial capital, hopes one day to start an online business importing furniture from her home country.

“I want more,” Li said. “I want to be a strong woman. I want independence.”

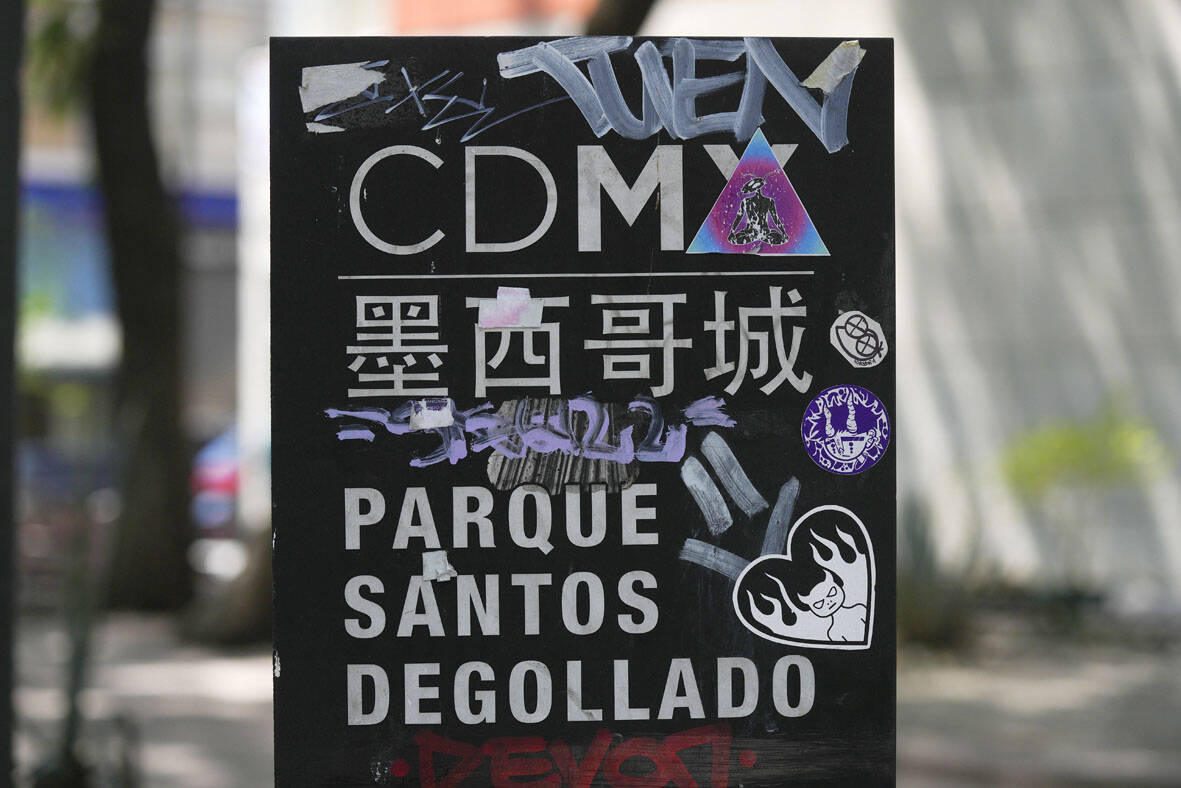

Photo: AP

Li is among a new wave of Chinese migrants who are leaving their country in search of opportunities, more freedom or better financial prospects at a time when China’s economy has slowed, youth unemployment rates remain high and its relations with the US and its allies have soured.

While the US border patrol arrested tens of thousands of Chinese at the US-Mexico border over the past year, thousands are making the Latin American country their final destination. Many have hopes to start businesses of their own, taking advantage of Mexico’s proximity to the US.

Last year, Mexico’s government issued 5,070 temporary residency visas to Chinese immigrants, twice as many as the previous year — making China third, behind the US and Colombia, as the source of migrants granted the permits.

Photo: AP

DEEP ROOTED DIASPORA

A deep-rooted diaspora that has fostered strong family and business networks over decades makes Mexico appealing for new Chinese arrivals; so does a growing presence of Chinese multinationals in Mexico, which have set up shop to be close to markets in the Americas.

“A lot of Chinese started coming here two years ago — and these people need to eat,” said Duan Fan, owner of Nueve y media, a restaurant in Mexico City’s stylish Roma Sur neighborhood that serves the spicy food of Sichuan, his home province.

Photo: AP

“I opened a Chinese restaurant so that people can come here and eat like they do at home,” he said.

Duan, 27, arrived in Mexico in 2017 to work with an uncle who owns a wholesale business in Tepito, near the capital’s historic center, and was later joined by his parents.

Unlike earlier generations of Chinese who came to northern Mexico from the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, the new arrivals are more likely to come from all over China.

Data from the latest 2020 census by Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography show that Chinese immigrants are mainly concentrated in Mexico City. A decade ago, the census recorded the largest concentration of Chinese in the northernmost state of Baja California, on the US-Mexico border across from California.

The arrival of Chinese multinationals is leading an influx of “people from eastern China, more educated and with a broader global background,” said Andrei Guerrero, academic coordinator of the Center for China-Baja California Studies.

In a middle-class Mexico City neighborhood, Viaducto-Piedad, near the city’s historic Chinatown, a new Chinese community has been growing since the late 1990s. Chinese immigrants have not only opened businesses, but have created community spaces for religious events and children’s recreation.

Viaducto-Piedad is recognized by the Chinese themselves as Mexico City’s true “Chinatown,” said Monica Cinco, a specialist in Chinese migration and general director of the EDUCA Mexico Foundation.

“When I asked them why, they would tell me because we live here. We have stores for Chinese consumption, beauty shops and restaurants just for Chinese,” she said. “They live there, there is a community and several public schools in the area have a significant Chinese population.”

SEARCHING FOR FREEDOM

In downtown Mexico City, Chinese entrepreneurs have not only opened new wholesale stores but have also taken over dozens of buildings. At times, they have become a source of tension with local businesses and residents, who say the expansion of Chinese-owned enterprises is displacing them.

At a mini-market in a bustling downtown neighborhood selling Chinese products such as dried wood ear mushrooms and vacuum-packed spicy duck wings, 33-year-old Dong Shengli said he moved to Mexico City from Beijing a few months ago to help manage the shop for some friends.

Dong — who has since found a job with a wholesaler importing knockoff designer sneakers and clothing — said he had worked at China’s National Energy Commission, but was persuaded by his friends to come here.

He plans to explore business possibilities in Mexico, but China still has a pull for him. “My wife and my parents are in China. My mother is elderly, she needs me,” he said.

Others are leaving China in search of greater freedoms. That’s the case for 50-year-old Tan, who gave only his surname out of concern for the safety of his family, who remain in China. He arrived in Mexico this year from the southern province of Guangdong and got a job for a few months at a Sam’s Club. Back home, he got by doing various jobs, including at a chemical plant and writing magazine articles during the pandemic.

But he chafed under what he described as a repressive atmosphere in China.

“It’s not just the oppression in the workplace, it’s the mentality,” he said. “I can feel the political regression, the retreat of freedom and democracy. The implications of that truly make people feel twisted and sick. So, life is very painful.”

What caught his attention in Mexico City were the protests that often pack the city’s main avenues — proof, he said, that the freedom of expression he longs for exists in this country.

LAND OF OPPORTUNITY

At the restaurant where she still helps out in the trendy Juarez neighborhood, Li said Mexico stands out as a land of opportunity for her and other Chinese who don’t have relatives in the US to help them settle there. She said she left China partly because of the competitive workplace culture and high home prices.

“In China, everyone saves money to buy a house, but it’s really expensive to get one,” she said.

Self-confident with a contagious smile, Li said she’s hopeful her skills working as a sales promoter for Chinese tech giant Tencent Games will help her get ahead in Mexico.

She says she has not met many Chinese women like herself in Mexico City: newcomers, young and single.

Most are married and are moving to Mexico to reunite with their husbands. “To come here is to face something unknown,” she said.

Li doesn’t know when she’ll be able to carry out her ambitious business plans, but she has ideas: For example, she imagines that in Henan province she could get chairs, tables and other furniture at a good price. Meanwhile, she is selling furniture imported to Mexico by a Chinese friend on the E-commerce platform Mercado Libre.

“I’m not married, I don’t have a boyfriend, it’s just myself,” she said, “so I’ll work hard and struggle.”

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just