Aug. 19 to Aug. 25

The situation was getting increasingly dire for the indigenous Mrqwang and Mknazi Atayal living near Hsinchu County’s Lidong Mountain (李崠山). Largely left alone during the first decade of Japanese colonization, they watched as their northern brethren fell one by one under the aggressive leadership of governor-general Samata Sakuma, who assumed the position in 1906.

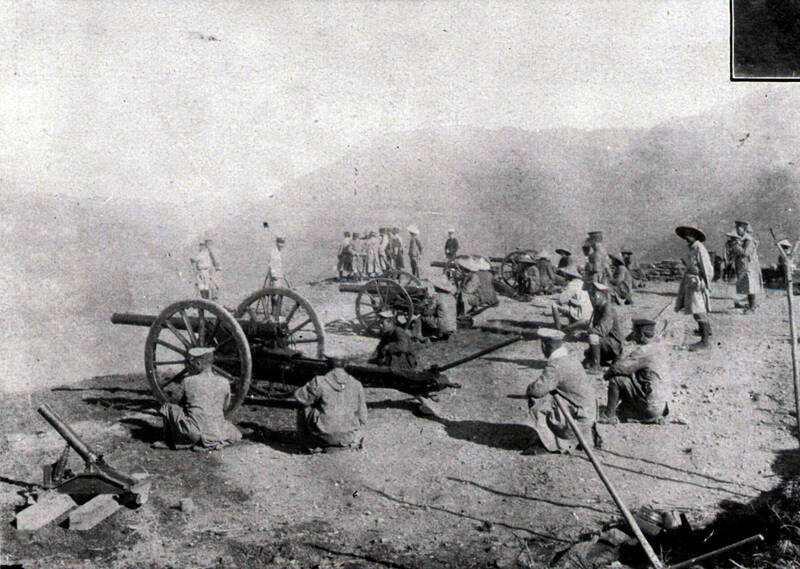

In late 1910, the Japanese defeated their close allies, the Mkgogan, and although the Mrqwang and Mknazi managed to repel an invasion the following year, the Japanese constructed frontier defenses and three hilltop fortresses with cannons aimed directly at their villages.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

After a powerful typhoon in August 1912 devastated Japanese frontline infrastructure and equipment, the Atayal struck back. They launched a coordinated attack on a 10km-stretch of the defense line, seizing one of the forts and pushing the cannons into the ravine. They then destroyed the remaining structures and set the gunpowder on fire, the loud explosions ringing through the ravines.

The win was short-lived as Japanese reinforcements soon arrived. By July 1913, the colonizers had full control over the region, ending the series of conflicts involving at least five Atayal groups now known as the Lidongshan Incident (李崠山事件, also known as the Tapung Incident).

It was the final stand for the northern Atayal, who were forcefully relocated so the government could exploit the region’s valuable timber and camphor.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

COVETED MOUNTAIN

Like the Qing Dynasty, the Japanese did not have full control over the mountainous indigenous areas. Sakuma, however, vowed to change that.

With superior numbers and firepower, the Japanese first targeted Atayal groups living in the southern part of today’s New Taipei City and eastern Taoyuan, prevailing in 1908 after a bloody two-year campaign.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

But Sakuma was not satisfied. In April 1910, he announced the “five year plan to govern the savages,” which aimed to bring every independent indigenous group in Taiwan under government control.

Ethnologist Daya Dakasi (better known as Kuan Da-wei, 官大偉) details the Tapung Incident in his 2019 book Zyaw pinttriqan nqu llingay Tapung (李崠山事件).

The term “Tapung” refers to branches snapping under thick snow. The traditional territory of the Mrqwang, Mknazi and Mkgogan met in this area, and the three enjoyed a close relationship, often banding together to resist invaders.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

The Japanese wanted Lidong Mountain not just for its trees. Camphor harvesters from Yilan, Taoyuan and Hsinchu all had to pass through the area, where they were often attacked by the Atayal who wanted to stem their encroachment. As the highest local point at 1,913m, the Japanese could set up artillery batteries at the top to keep the surrounding villages in line.

“The Japanese attacked the Atayal to seize our land, to fell our trees,” Paqiy Village resident Liu Jen-ching (劉仁青) tells Daya Dakasi. “Without land and without trees, there would be no more Atayal. Of course our ancestors had to fight.”

ASSAULTS ON TAPUNG

The 1,000-strong Mkgogan were partially subdued in previous conflicts, but many continued to fight, fleeing beyond the defense lines and attacking frontier guards, police stations and road workers.

The Japanese decided to deal with them first. To prevent allies from coming to their aid, they closed in from two sides in May 1910. A contingent of about 3,000 troops from Yilan focused on the Mkgogan, while a force of 1,200 from Hsinchu dealt with the Siakaro and Maibarai. The Hsinchu brigade achieved its objective within a month, but the Yilan brigade was having trouble. The Japanese sent reinforcements from Hsinchu, but they were attacked en route by the Mrqwang. The Atayal resistance was fierce, but by September, the Japanese had seized the saddle area of Lidong Mountain.

The tide turned as 1,300 more troops arrived from Taoyuan, and in late October, the Japanese held a surrendering ceremony, where the Mkgogan handed over their firearms. They called for the Mrqwang and Mknazi to do the same, but the two had agreed to refuse and continue fighting.

The Japanese set up a fort and battery on Balung Mountain, from where they could fire at all three groups. Meanwhile, the Mrqwang and Mknazi launched sporadic attacks throughout the year.

On Aug. 2, 1911, a force of over 2,000 made its way toward Lidong Mountain. One contingent successfully took the peak and began constructing fortifications, but the others struggled as the Mkgogan sent warriors to help despite their previous surrender. The Japanese repeatedly tried to rush up the peak, but the Atayal ambushed them from above and engaged them in hand-to-hand combat. Only a handful of Japanese made it to the top.

The Japanese were further hampered by inclement weather, which knocked out their telecommunication lines. The fighting concluded in November, and although the Japanese failed to subjugate either group, they built three mountaintop batteries that would greatly aid their future operations.

FINAL PHASE

The 1912 Atayal offensive was successful at first, but they were driven back behind the defense line on Oct. 1.

The Japanese pushed forward on Oct. 3, but by this time the Atayal had learned a thing or two from their enemy as they began building similar mountaintop fortifications. This battle lasted until Dec. 13, concluding with the surrender of the Mrqwang. The Japanese then expanded the forts on Balung and Lidong mountains and added several smaller ones on the nearby hills.

Only the Mknazi remained, numbering around 630. The Japanese struck on June 25, 1913 with a 2,780-strong force, but they struggled against the much smaller Atayal resistance. On July 7, Sakuma personally arrived at the battlefield, setting up command headquarters at Tapung Fort (formerly known as the Lidong Moutain Fort).

Around this time, the Mknazi fighters multiplied in number — their close relatives, the previously surrendered Siakaro, had sent help. But the Japanese called for even more help, and by July 17, the Atayal began surrendering and turning in their firearms.

After the war, the Japanese sought to erode the ties between the groups. In one instance, they took advantage of a hunting grounds dispute between the Mrqwang and Mknazi, supplying them with guns to widen the conflict before stepping in as mediator. They also relocated the villages to lower ground and encouraged them to farm rice, greatly altering their lifestyle.

Today, Lidong Mountain is popular among hikers, listed among Taiwan’s “Small 100 Peaks” (小百岳) under 3,000m. The Tapung Fort still stands today and became a historic relic in 2003.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name