The wreckage of two scooters are just visible from beneath white sheets — the kind that is laid over a deceased body at the scene of an accident.

Intermittently, bright lights are projected onto the sheets. This is the footage from Yang Chia-shin’s (楊佳馨) two motorbike dashcams as she rolled down Keelung Road (基隆路) in Taipei one fateful evening in February, 2022.

The collision is sudden, a 360-degree spin before she is thrown from the vehicle.

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

The perspective change is captured by both cameras, one to the front, one to the rear, as the motorbike careens out of control, until all movement stops.

This dual installation is the main focal point of Return to the Scene (重返現場), a series of artworks on view at Hualien’s Good Underground Art Space (好地下藝術空間), which document Yang’s scooter accident and her slow recovery thereafter.

“I’ve tried to reconstruct the sensitivity of the moment between life and death,” she says.

Photos: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

Yang hasn’t just used video but a range of media and materials to recreate the sensory experience of the accident in the gallery space.

There are growls of motorbike engines revving.

She’s mounted a broken wingmirror on the wall framing a photograph of the point where she came off the road.

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

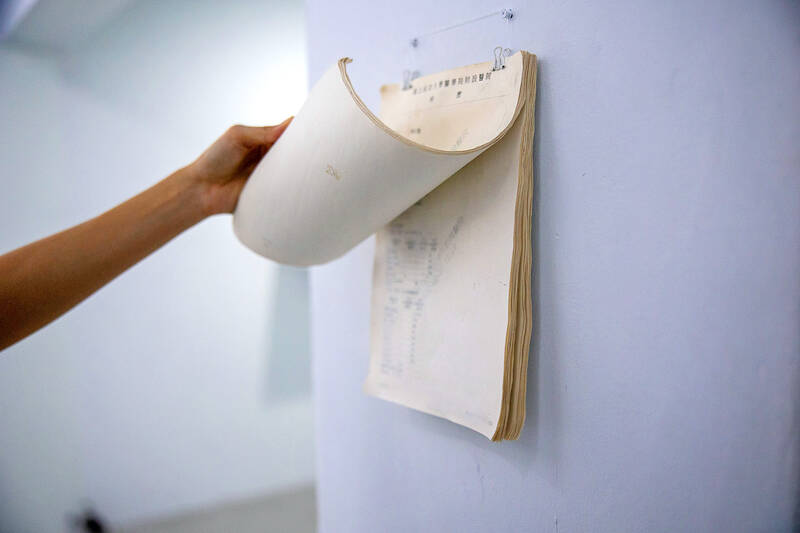

The crash required two collar bone operations and has left her shoulder scared. Yang collected a journal of doctor’s reports in the wake of the accident.

But far from being morbid or depressing, Yang’s work is more a form of exorcism — the artist’s way of working through “emotional layers” with the “aim of cleansing preconceived perceptions and heal her trauma,” as the introduction puts it.

One video shows her cleaning her scooter in an artwork titled The Motorcycle’s Rebirth (機車的重生). “It’s actually me washing away the pain of the past.”

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

“There’s movement in Yang’s work,” says the gallery’s art director Tien Ming-chang (田名璋), adding that there is a unique dynamism, which “invokes a sense of instability.”

The video is projected onto a shroud-like white cloth, which also “serves as a metaphor for the presence of death,” he says.

White symbolizes death, and is associated with the robes worn in traditional funerals.

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

In the wake of the enormous earthquake on April 3, I asked how Tien thinks Hualien residents might react to work that addresses life’s fragility and human mortality.

“Facing natural disasters is not a matter of the last two or three days for Hualien people. It is part of our DNA,” he says.

Although locals have grown accustomed to living on a fault line, he says, “Yang explores issue that we cannot escape,” in her artwork, which he believes, “will help people understand life better as a result.”

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as