July 15 to July 21

Depending on who you ask, Taiwan Youth (台灣青年) was a magazine that either spoke out against Japanese colonialism, espoused Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) ideology or promoted Taiwanese independence.

That’s because three publications with contrasting ideologies, all bearing the same Chinese name, were established between 1920 and 1960. Curiously, none of them originated in Taiwan.

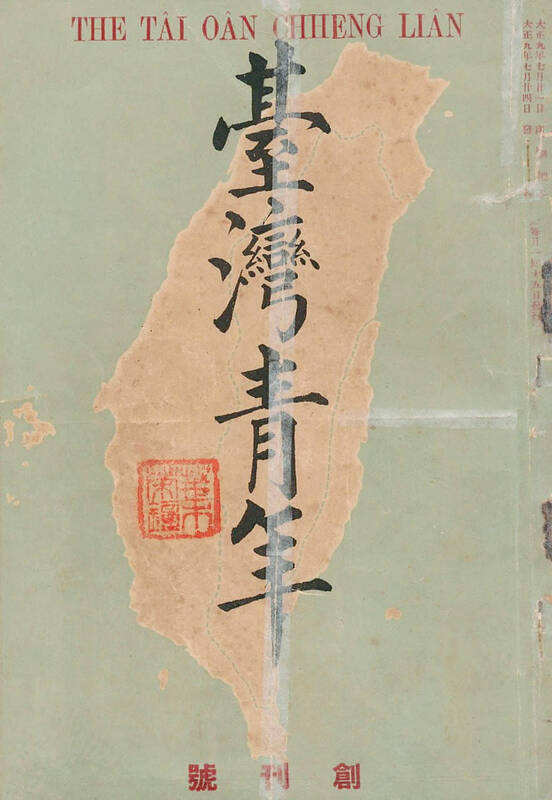

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The best known is probably The Tai Oan Chheng Lian, launched on July 16, 1920 by Taiwanese students in Tokyo as part of the growing non-violent resistance movement against Japanese colonial rule. A crucial part of the effort was to promote Taiwanese culture and identity, and create space for local voices in a Japanese-dominated media landscape.

Written in Chinese and Japanese, the staff announced in the first issue that their focus would be on self-determination, gender equality and labor rights. The content became increasingly critical of the colonial government, leading the Japanese authorities to ban five out of the 18 issues and censor parts of three more. It is considered a precursor to the influential Taiwan Minpao (台灣民報) newspaper.

The second Taiwan Youth was also anti-Japanese, founded in China in 1943 by the Taiwan Volunteers (台灣義勇隊) who aided the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) during World War II. It shifted from war propaganda to Chinese patriotism after Japan’s surrender, relaunching in Taiwan on Nov. 12, 1945 — the birth anniversary of KMT founder Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙).

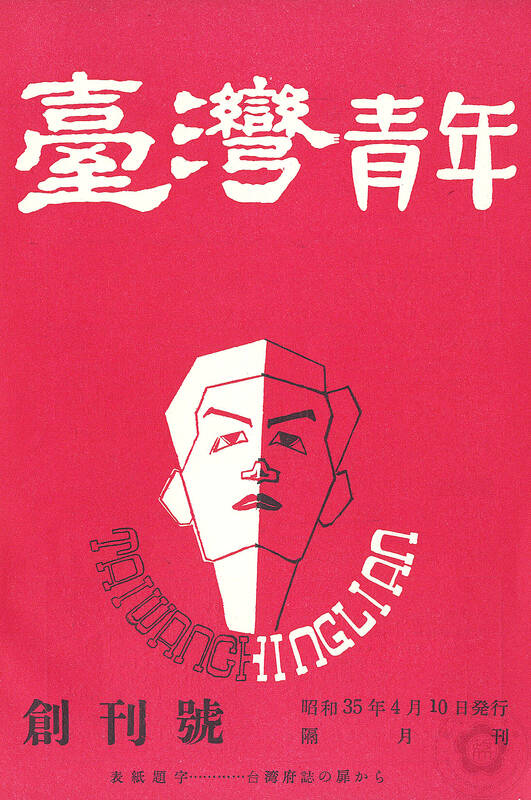

Photo courtesy of National Chengchi University Libraries

The final iteration, Taiwan Chinglian, was started in 1960 by exiled independence activists in Tokyo. In addition to promoting Taiwanese nationalism, it devoted significant editorial space to the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed in 1947, which was a taboo topic under the KMT well into the 1980s. It was the longest-running out of the three, lasting 500 issues until 2002.

UNARMED RESISTANCE

While armed revolts against the Japanese by Han Taiwanese had died down by the 1920s, local intellectuals continued the fight through non-violent means.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

In January 1920, the first Taiwanese political activist group, the New Peoples’ Society (新民會), was inaugurated at businessman Tsai Hui-ju’s (蔡惠如) house in Tokyo. Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) of the prominent Wufeng Lin family served as president with Tsai as his deputy, and most members were Taiwanese students or recent graduates.

Tsai, whose business was faltering, set aside some money to launch the group’s mouthpiece, The Tai Oan Chheng Lian, hoping to at least publish three issues, writes historian Chuang Sheng-chuan (莊勝全) in a 2019 reissue of the magazine. However, some of Taiwan’s wealthiest men immediately pitched in, including Lin, Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮) and Yen Yun-nian (顏雲年). Tsai Pei-huo (蔡培火) served as editor-in-chief and spokesperson, with Lin Cheng-lu (林呈祿) and Peng Hua-ying (彭華英) as the main editors.

“Collecting domestic and overseas ideas and writing in Japanese and Chinese, we hope to respond to global events and follow modern trends to advance the wisdom of Taiwanese. Although we dare not claim to be the ears and eyes of Taiwanese society, we wish to serve as a harbinger of public discourse for the island’s residents,” the introduction read.

CENSORED AT HOME

The magazine gained considerable support in Japan, which was going through the post-World War I Taisho Democracy Movement. The first issue featured congratulatory calligraphy by Kenjiro Den, governor-general at the time, and contained pieces by prominent Japanese activists, scholars and politicians.

Meiji University professor Izumi Akira wrote in his piece that Taiwanese “must realize that Taiwan does not belong to the governor-general’s office, it belongs to Taiwan’s residents.” Tsai elaborated on this point in the fourth issue, adding that the government must treat Japanese, Taiwanese and indigenous living in Taiwan equally.

However, the magazine was subject to close scrutiny before being distributed in Taiwan. The first two issues were only sold in Japan due to procedural complications, and the fourth was banned for unspecified reasons.

The censors struck again in March 1921, claiming inappropriate wording. Instead of rewriting the material, the staff simply blotted out the offending parts and republished the rest wholesale. This seemed to anger the authorities, who cracked down on the magazine for the rest of the year. The magazine staff complained to the Japanese central government, and also submitted a banned article to two Japanese-run newspapers in Taiwan. Both ran it without any problems, and staff complained about the unequal treatment between Taiwanese and Japanese publications.

They also collaborated with similar publications such as the Korean Asia Kunglun, which ran in its first issue a detailed account on the suppression of The Tai Oan Chhing Lian.

While the content at first mostly revolved around building Taiwanese cultural confidence and awareness, it became increasingly critical. For example, the banned final February 1922 edition contained analysis of the Irish independence movement and criticism of the government’s monopoly on alcohol, free speech restrictions and the treatment of Taiwanese students in Japan.

GOVERNMENT PROPAGANDA

The second Taiwan Youth ceased publication in China in July 1944, but was revived in Taiwan after the war under the Three Principles Youth Group (三民主義青年團), which absorbed the Taiwan Volunteers.

The woodblock print cover of the first Taiwan issue showed a young man running while reading a copy of Sun’s Three Principles of the People, with an image of Taiwan in the background. Each issue opened with words from KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), and the first half contained patriotic propaganda and articles by officials and youth group leaders.

The second part featured submitted entries. Topics included “Sun Yat-sen Thought” (國父思想), national and local policy, youth issues, Taiwanese history and culture and the arts. There were travelogs, essays, op-eds, reviews, poems and artwork (mostly woodblock prints).

Historian Ho Yi-lin (何義麟) writes in a National Museum of Taiwan Literature entry that the publication ignored the fact that the majority of youth in Taiwan could not read Chinese. In fact, an article in the final edition (March 29, 1946) by Department of Education chief Fan Shou-kang (范壽康) admonished Taiwanese for clinging to the Japanese language.

“In the ensuing years, our education policy must emphasize our national literature, language and history, so that our Taiwanese compatriots can, within the shortest amount of time, be restored to their original state 50 years ago. We must eradicate all the poisoning caused by the enslaving education and obscurantist policies [by the Japanese].”

PURSUING INDEPENDENCE

The third version, Taiwan Chinglian, was run by the Taiwanese Youth Independence League. The magazine’s interest in exploring the 228 Incident was evident, as founder Ong Iok-tek (王育德) fled Taiwan after his elder brother Ong Iok-lim “disappeared” during the event’s aftermath. It’s believed that the elder Ong was targeted because he prosecuted KMT officials.

Taiwan Chinglian “was the most influential overseas Taiwanese publication in the 1960s,” states the National 228 Memorial Museum Web site. Originally published only in Japanese, it switched to Chinese in February 1976.

In 1965, it was the first to publish independence activist Peng Ming-min’s (彭明敏) “A Declaration of Formosan Self-Salvation,” as Peng was arrested before he could publicize the statement the previous year. A copy made its way to the US, which eventually led to the half-page “Formosa for Formosans” advertisement in the New York Times. This echoed The Tai Oan Chhing Lian’s Taiwan belongs to Taiwanese sentiment, but under very different circumstances.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.