It’s one of those strange but immutable truths of the movies that a song like Earth, Wind & Fire’s September can play in roughly a thousand films before a movie about a dog and a robot comes along and blows them all out of the water.

The animated Robot Dreams is wordless, so the songs play an outsized influence in conjuring its whimsical and gently existential tone. But Pablo Berger’s Robot Dreams, a 1980s New York-set fable about loved ones who come and go, doesn’t just use September for a scene or even two. It’s the soundtrack to the friendship between Dog and Robot (yes, those are the protagonists’ names in this disarmingly simple film), and its melody returns in various forms whenever they’re reminded of each other.

To a remarkable degree, Robot Dreams has fully imbibed all the melancholy and joy of Earth, Wind & Fire’s disco classic. Just as the song asks “Do you remember?” so too does Robot Dreams, a sweetly wistful little movie that, like a good pop song, expresses something profound without wasting a word.

Photo: AP

Remembering is also helpful when it comes to the film, itself. I first saw Robot Dreams over a year ago at the Cannes Film Festival. Its release comes months after Robot Dreams was Oscar nominated for best animated film. But for whatever reason, the film is only arriving in North American theaters this Friday.

It’s an unconventional release pattern for an unconventional film. Robot Dreams, adapted from Sara Varon’s 2007 graphic novel, is likewise an all-ages movie in a curious way. It’s very much for kids, but it’s also so mature in its depictions of relationships that older generations may swoon hardest for it.

Robot Dreams begins in the East Village where Dog lives a rather lonely life. Before he sits down to eat a microwave dinner, he notices his solitary reflection in the TV screen. An ad, though, sparks Dog to order the Amica 2000. A few days later, a box arrives, Dog assembles its contents and soon a friendly robot is smiling back at him.

Photo: AP

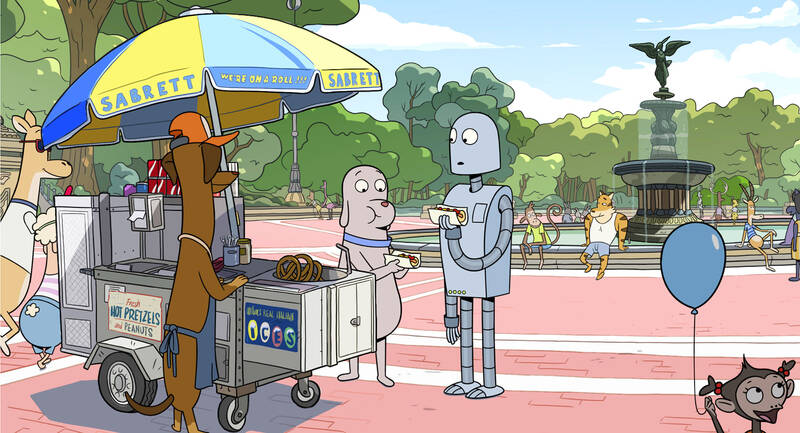

Together, they have a grand old time around a New York colorfully rendered with pointillist detail. They jump the subway turnstiles, visit Woolworths and rollerblade in Central Park (with September playing on the boombox). But after an outing to Playland (which looks much more like Coney Island), Robot’s enthusiasm gets him into some trouble. After frolicking in the water, he lies down on the beach and later finds he can’t move. This may be a movie about a Dog who rollerblades and a Robot who eats hot dogs, but the scientific reality of rust is one suspense of disbelief too far for Robot Dreams.

Despite all of Dog’s efforts, Robot is stuck, and, this being September, the beach is soon closed for the off-season. Much of Robot Dreams passes through the seasons while Robot dreamily sleeps through the winter and Dog is forced to go on with his life, and maybe try to meet someone new.

The dreams of each can be surreal; Dog has a bowling alley visit with a snowman who bowls his own head, while Robot imagines a Wizard of Oz-like fantasy. But both are consumed by fears of their friend’s abandonment while progressively finding new experiences and friends. New characters enter, with their own New Yorks (kite-flying in the park, rooftop barbecues) and their own soundtracks. Robot Dreams movingly turns into a story about moving on while still cherishing the good times you once shared with someone — a valuable lesson to young and old, in friendship and romance.

And even this sense of memory runs deeper in Robot Dreams than you might be prepared for. Berger, the Spanish filmmaker whose movies include the 2012 black-and-white silent Blancanieves, has filled his movie with countless bits of a bygone past, from Atari to Tab soda. The name Amica 2000 could be a pun for the Amiga 500, the early computer and harbinger of our digital present. Even more dramatic, though, is the way the Twin Towers often loom in the background in a film so connected to the month of September. There, too, is a poignant symbol of companions, friends and family members who vanished, but whose memories still stir within us.

This is, you might be thinking, a lot for a cartoon about a dog and a robot to evoke. And yet Robot Dreams does so, beautifully. And it will leave you curiously lifted by the spirit and lyrics of one of the most-played wedding songs of all time: “Only blue talk and love, remember/ The true love we share today.”

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the

“Far from being a rock or island … it turns out that the best metaphor to describe the human body is ‘sponge.’ We’re permeable,” write Rick Smith and Bruce Lourie in their book Slow Death By Rubber Duck: The Secret Danger of Everyday Things. While the permeability of our cells is key to being alive, it also means we absorb more potentially harmful substances than we realize. Studies have found a number of chemical residues in human breast milk, urine and water systems. Many of them are endocrine disruptors, which can interfere with the body’s natural hormones. “They can mimic, block

Nearly three decades of archaeological finds in Gaza were hurriedly evacuated Thursday from a Gaza City building threatened by an Israeli strike, said an official in charge of the antiquities. “This was a high-risk operation, carried out in an extremely dangerous context for everyone involved — a real last-minute rescue,” said Olivier Poquillon, director of the French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem (EBAF), whose storehouse housed the relics. On Wednesday morning, Israeli authorities ordered EBAF — one of the oldest academic institutions in the region — to evacuate its archaeological storehouse located on the ground floor of a residential tower in