April 15 to April 21

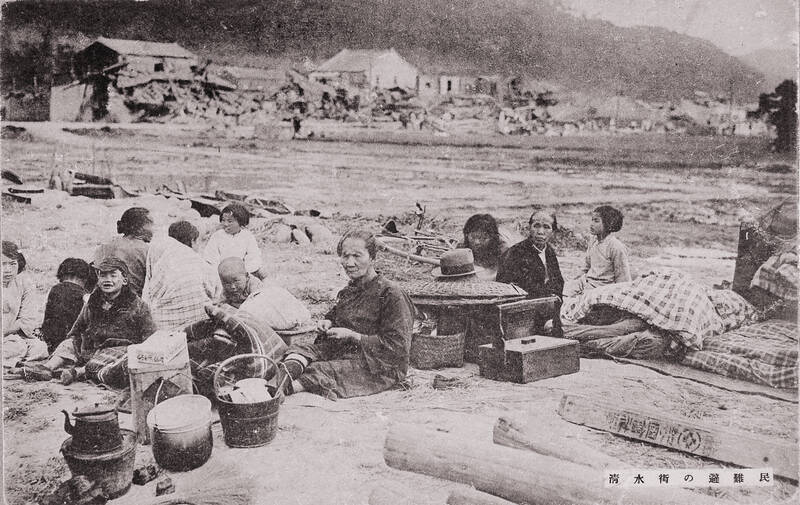

Yang Kui (楊逵) was horrified as he drove past trucks, oxcarts and trolleys loaded with coffins on his way to Tuntzechiao (屯子腳), which he heard had been completely destroyed.

The friend he came to check on was safe, but most residents were suffering in the town hit the hardest by the 7.1-magnitude Hsinchu-Taichung Earthquake on April 21, 1935. It remains the deadliest in Taiwan’s recorded history, claiming around 3,300 lives and injuring nearly 12,000. The disaster completely flattened roughly 18,000 houses and damaged countless more.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

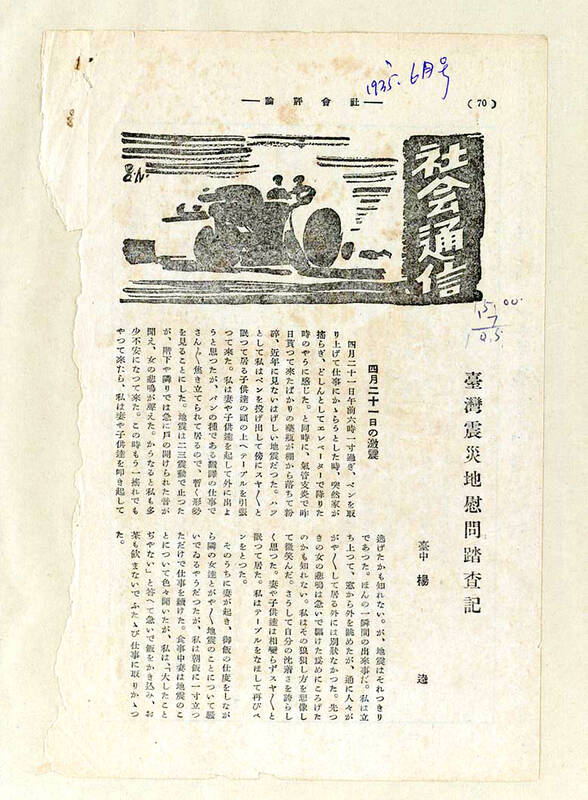

The social activist and writer jumped into the relief effort, only to be further dismayed by the callousness of the local officials and prominent families, who hoarded aid supplies while the masses barely had enough to eat. He detailed the experience in a highly critical piece for Social Commentary magazine, much to the annoyance of the authorities.

“Investigation and relief work in Taiwan’s earthquake disaster zones” (台灣地震災區勘察慰問記) stands out among the numerous first-hand accounts of the event as one of Taiwan’s earliest works of literary reportage, which Yang would later become a proponent of.

On the other end of the spectrum is the Great Central Taiwan Earthquake New Song (中部大震新歌) a lengthy composition of seven-character verses meant to be performed as a liamkua (唸歌) — a folk storytelling style that mixes singing with the spoken word.

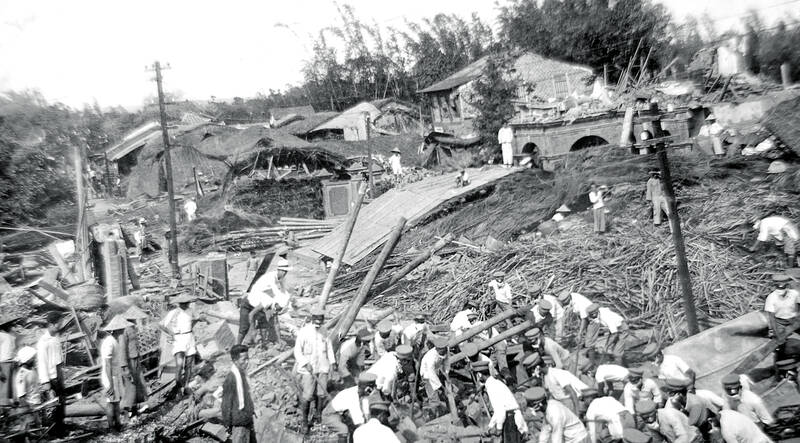

Photo Courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan History

Unlike the Japanese-educated Yang, author Lin Ta-piao (林達標) never received formal schooling, and liamkua was a popular way for the illiterate who didn’t have access to radios to learn about recent events.

Lin claims to have personally visited most of the disaster zones for research, and Great Central Taiwan Earthquake New Song is noted for its eyewitness reportage style and accuracy in details.

DANGEROUS HOUSES

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

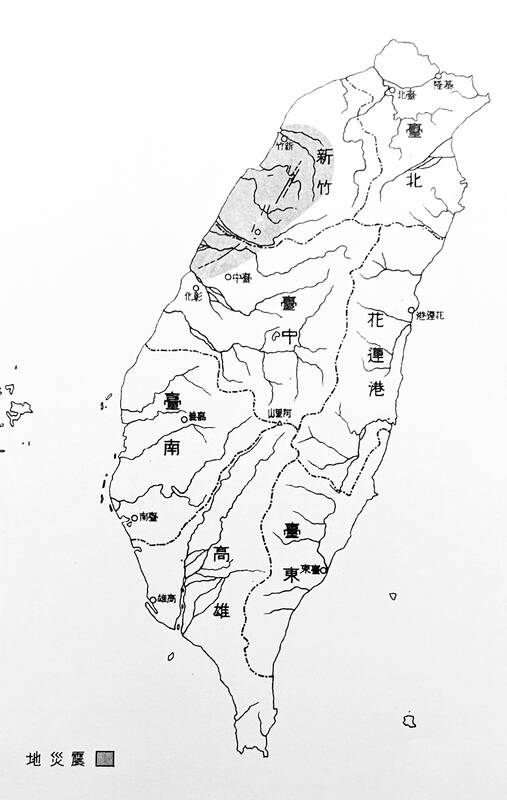

With its epicenter near Guandao Mountain in today’s Miaoli County, the earthquake affected an area of 315 square kilometers between southern Hsinchu and northern Taichung. As it happened at 6:02am, many people were still in their houses.

Yang had just woken up and picked up his pen when his residence in Taichung began to shake.

“It felt like I was in an elevator that had suddenly dropped. My bronchitis medicine bottle fell from the shelf and smashed on the ground,” he wrote.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan Literature

He grabbed a table and held it over his sleeping children, and was about to wake them up when the tremors stopped. His editors had been hounding him for his translation work that was past deadline, so he told his wife to go back to sleep while he began writing.

It was only after he and his family ventured out later that day that he realized the severity of the situation, which he describes in detail.

Sen Hsun-hsiung (森宣雄) and Wu Jui-yun (吳瑞雲) write in Great Taiwan Earthquake: A Record of the 1935 Central Taiwan Disaster (台灣大地震:1935年中部大震災紀實) that this quake was particularly devastating as it happened over two fault lines located directly under rural settlements. The affected areas had a high concentration of houses made from rammed earth brick, which are cheap but prone to collapse.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

In his article, Yang criticizes the government for not putting enough effort into monitoring seismic activity and ensuring that houses in Taiwan were earthquake-proof, noting that the Japanese-built village hall in Tuntzechiao did not collapse. Lin also mentions the rammed earth houses as the reason for the high death toll, and advises people to build with wood.

“Rural Taiwanese villages today are full of these dangerous houses, but people do not have the money to rebuild or repair the parts that need to be fixed,” Yang writes.

The government actually made significant upgrades to earthquake detection and research following the tragedy, and also banned the rammed-earth structures. The devastated areas were rebuilt with wider, straighter streets and more open spaces for people to shelter.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DISASTER SONGS

It was not uncommon for liamkua practitioners to sing about natural disasters back then, writes Wang Yi-hua (王怡樺) in “Studying the meaning behind Taiwanese liamkua booklets that describe natural disaster” (臺灣歌仔冊表述天災的意涵探究). In fact, three different liamkua compositions appeared in 1935 alone.

Lin is unusual among liamkua authors in that he took great pride in factuality. In one verse, he invites readers to scold him if they found any errors. The lyrics intersperse facts about the disaster, accounts of how people in certain towns died as well as the relief effort.

In one section, Lin lists the exact number of victims in each prefecture, then breaks them down by town or region. Wang writes that the statistics are nearly identical to those listed later in the governor-general’s office report.

Like Yang, Lin sprinkles his personal feelings into the prose, noting how he cried when visiting the disaster scenes. He curses the looters and those who took advantage of the helpless, and tells readers not to blame the heavens as “life and death are predestined.”

Lin praises the government’s efficient response while lauding the civilian effort and how everyone tried to help out however they could. He exhaustively lists all the items people donated, from large sums of cash to old clothes and cooking oil. “It doesn’t matter how much you give,” he writes.

LOCAL INJUSTICES

On April 22, Yang and more than 20 members of the Taiwan Arts and Culture League (台灣文藝聯盟) set up relief headquarters at the Taichung News (台中新報) office and spent the next two weeks raising funds, delivering goods and helping out in the afflicted areas.

“We always promote our societal ideals, but ideals mean nothing if you don’t tackle the immediate problems,” Yang writes. “Right in front of us are people who can barely walk, on the brink of starvation, don’t have clothes to wear, a home to stay in or food to eat; some don’t even have a place to bury the bodies of their loved ones. At this point, those who still espouse ideals but remain on the sidelines are betraying their beliefs.”

Although newspapers ran articles praising the government relief effort, Yang writes that many villagers were barely given enough food to survive, lacking the strength to finish erecting their temporary shelters. Yang and other volunteers tried to convince local officials to provide more aid and some were sympathetic, but others less so. One family of three in Taichung’s Cingshui District (清水) was given only one bowl of rice per day, and when the elderly grandma begged the distribution officers for more, they chased her away.

In Tuntzechiao, residents drew lots for rations; some received two or three portions while others got nothing. A nurse told them that the best supplies were already seized by families of high status.

Yang also observed that the poor were more generous than the wealthy, who often refused to donate unless they got something in return. There was the blind beggar who insisted on giving what she had to the relief effort, and the churchgoing wealthy merchant who declined to offer a single penny. One elderly woman told authorities to give her ration of milk to the children who had lost their mothers.

Japanese authorities ended their efforts on May 6, but Yang returned to Tuntzechiao on June 4. Sadly, the situation was just as bad. The initial fervor to help had died down and the government had ended its relief efforts, leaving the victims to be “slowly forgotten.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that would limit semiconductor

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South