The earthquake that struck last Wednesday was tragic. As of this writing, 12 are dead, over 1000 injured and 18 are worryingly, still missing.

Though they covered these facts, the international press mostly marveled at Taiwan’s response, using words like “resilient” and “well prepared.” Even the Japanese, with their own extensive experience with seismic activity, were impressed by the enclosed blue shelters set up in a school gym, which offered to those rendered homeless privacy and dignity, rather than the typical rows of bunks.

A CNN reporter on the scene, with a partially-collapsed building dramatically posed in the background, was agog at the low death count and how, for the most part, Hualien City (花蓮) was going about its business normally.

Photo: Reuters

Many other news outlets covered how the Taiwanese had done a remarkable job in earthquake preparedness and wrote glowingly on the giant steel ball in Taipei 101 that stabilizes the building during earthquakes and in typhoon-strength winds.

The Japanese, with their customary generosity and thoughtfulness, donated considerable amounts of aid money. Yet this time, unlike after the 921 earthquake of 1999, no international rescue teams were needed — Taiwan’s rapid response professional rescue teams had it covered.

The National Land Management Agency on Friday announced that 430 buildings were damaged by the earthquake, but only 18 were classified as “red zones” and 34 as “yellow zones.” They publicized structural warning signs for the public to look out for and asked anyone spotting these signs to contact the agency so they can send out structural engineers, and reminded the public that subsidies are available to fix weak load-bearing sections.

Photo: EPA

The international press was correct that the number of casualties and buildings damaged after a magnitude 7.2 earthquake was remarkably low, as tragic as it is that the numbers are not zero. Almost anywhere else in the world earthquakes of this scale would have caused orders of magnitude more casualties and destruction.

In spite of their good coverage, the international press missed something crucial: the core reason why Taiwan is one of the world’s best at responding to natural disasters.

THE REAL REASON TAIWAN IS SO GOOD AT THIS

Photo: Reuters

The international press noted that Taiwan had learned a lot from the 921 earthquake and had significantly strengthened building codes in the aftermath. Rescue teams and protocols were also beefed up.

It was not said explicitly, but reading between the lines, it was implied that Taiwan being wealthy ensures a higher level of resources are available. That certainly helps.

That Taiwan is so seismically active and has a lot of experience is also a factor. That Taiwanese are nimble, practical and excel at logistics could also be important contributors to the country’s success.

Yet, all of these factors would have contributed little to nothing without one core factor: Democracy.

Democracy is the force that ensures all those rules, resources and experience are put to any good use. Without democracy, this earthquake would have caused massive destruction and the international press would not be so impressed.

How do I know this? Because I witnessed what Taiwan was like before democracy and watched the transition. The difference is night and day.

HOW TAIWAN USED TO BE

Taiwan’s authoritarian era as defined by the Act on Promoting Transitional Justice is “15 August 1945 to 6 November 1992.” From 1992 to 1996 four of the five branches of government remained in the hands of the old Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) led system and it was only in 2000 that the executive branch finally saw a transfer of power to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).

I arrived in 1988, the same year Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) passed away and the year before democracy activist Deng Nan-jung (鄭南榕) self-immolated to protest the government trying to imprison him for “insurrection” for having the temerity to write a proposal for a constitution for a Republic of Taiwan.

One frequent topic of discussion at the time was how shoddy Taiwanese construction was. Soon after I arrived, a just-constructed expressway overpass in Taipei collapsed.

There are roughly two periods of shoddy construction. The first was the early KMT-era.

It is frequently claimed that during that period — when the KMT monopolized resources — they thought because they were going to “retake the mainland” in the near future there was no point in building anything to last.

The second period is the economic boom times, roughly from the mid-1970s through the end of the 1990s. During this period, considerable private resources joined the construction party, and there were a lot of building because of all the money sloshing around.

There was no incentive for construction companies to build quality buildings. The money was in cutting corners, ignoring regulations and short-changing the client with subpar materials as much as possible.

At the time, with all the money involved, almost inevitably organized crime became deeply involved in the construction industry. These were not the most ethical people to begin with.

Since the one-party state had no challengers, they did not care very much what the public thought and did everything they could to ensure that the public did not make their concerns known if it involved criticizing the government. Potential prison time is not conducive to productive public debate.

SALAD CANS AND RADIOACTIVE REBAR

The contractors would bribe inspectors to look the other way. This was understood as common practice that was how inspectors made their money.

Government jobs at the time were largely gotten through personal ties, ties to the KMT or nepotism. Qualifications could easily be faked.

As long as what they built did not randomly collapse, leading to people dying without anything to blame it on — such as an earthquake — they could get away with nearly anything. They got very wealthy doing just that.

One common practice was to use salad oil cans in construction. During one period it was discovered that some extremely unscrupulous people were using radioactive rebar in projects in and near Taipei, which led to panic and many apartment buildings had to be checked with Geiger counters.

After natural disasters plenty of buildings would collapse. There would be talk of improving building codes, and sometimes new codes were written, only to be promptly ignored as things went back to the way they had been.

This is the type of system we see in China today, with their notoriously awful “tofu dregs” (豆腐渣) construction. Tragically, countless Chinese will continue to lose their lives in natural disasters due to a system that does not prioritize their safety.

Once political power was put in the hands of voters, things began to change in Taiwan. It was a process that happened over time, in different places at different paces. Some say it still has not entirely happened yet in “Miaoli Nation” (苗栗國).

Public pressure now mattered. The newly emboldened free press could make a politician’s life a living hell if it appeared that their malfeasance had led to deaths in a disaster.

As politicians learned the ropes of democracy, navigating the free press and learning how powerful public pressure could be, politicians started to adapt. As politicians grew to understand how completely they could be roasted by the people, they became ever more proactive in promoting safety and taking pre-emptive precautions.

They began to care about the professionalism of their inspectors, the performance of their rescue workers and taking the time and energy to contingency plan. A leader that performed well in a crisis, or is seen as to have done a good job containing a disaster is praised in Taiwan, one that does not is punished.

Democracy incentivized everything into existence that the international press praised. Without it Taiwan would have continued with the old system that gave little priority to human life.

Courtney Donovan Smith is a regular columnist for Taipei Times, the central Taiwan correspondent at ICRT FM100 Radio News, co-publisher Compass Magazine, co-founder Taiwan Report (report.tw) and former chair of the Taichung American Chamber of Commerce. Follow him on X: @donovan_smith.

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

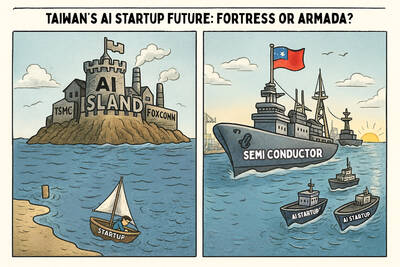

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government