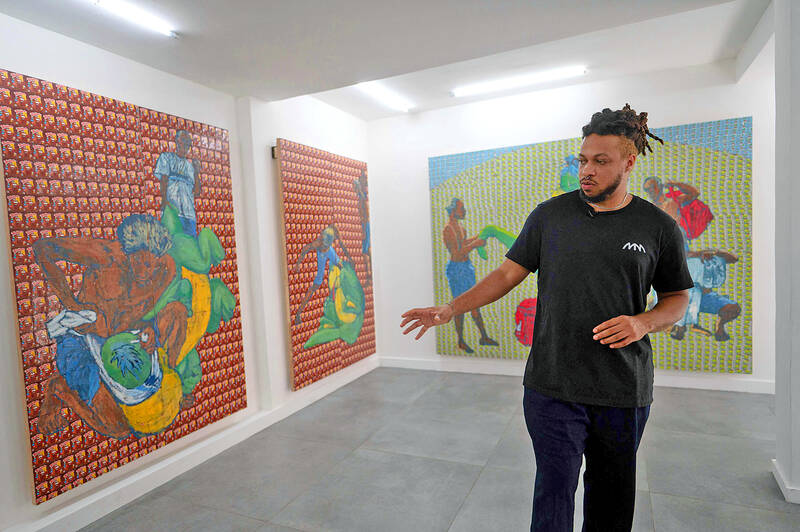

Like in most cities, Rio’s galleries are concentrated in its affluent neighborhoods. But artists like Maxwell Alexandre are trying to change that, hoping to “give access to what was previously the art of the bourgeoisie, something exclusive,” the 33-year-old said.

Alexandre grew up in the shantytown of Rocinha, Brazil’s second most populous favela, and where he opened the Pavilhao 2 display space last year. At the moment, he is exhibiting a collection of his own works that last year was on display at a gallery in the exclusive sixth arrondissement of Paris, France.

Entitled Entrega: one planet. one health, the exhibit includes paintings of daily life in Rocinha.

Photo: AFP

A series of three works shows children dressed in school uniforms carrying bags from a food delivery company: a commentary on pervasive child labor.

Another aim of Alexandre — who has also exhibited in Spain and the US — is to make favela residents art owners.

“I want people who live in the favela to see my work not only in the gallery but also at home,” he said.

Photo: AFP

Alexandre is selling his works at the below-market price of about 1,000 reais (US$200) apiece though even this may be a high ask of many.

ART POWER

The gallery also aims to draw visitors from outside, such as 45-year-old teacher Mariana Furlonis, who said: “It’s great, because art is usually very elitist.”

Alexandre acknowledges that most visitors do not come from the favela, whose impoverished inhabitants have other, more pressing priorities.

But though he is often advised to focus his efforts on such artistic hubs as Berlin or New York, Alexandre prefers to stay in Rio, where he says his creativity is inspired by the heat, the violence, the omnipresent poverty.

About 30 kilometers away, fellow artist Allan Weber, 31, opened a gallery in his childhood favela, Cinco Bocas, in 2020.

His works had recently been exhibited at the Miami contemporary art fair Art Basel.

Back in Rio, he uses his gallery to give exposure to lesser-known local artists.

“It’s a place of exchange between the favela and people who come from elsewhere,” he said.

His target clientele are people like himself who grow up without access to downtown museums, but also more affluent friends reluctant to visit the favelas, frequent targets of heavy-handed police operations.

“I spent all my childhood seeing weapons, and thanks to art, I was able to give them a new meaning,” Weber said.

One of his creations is an assault rifle made from camera parts.

‘NO PLACES LIKE THESE’

Since last September, Weber’s gallery has hosted an exhibition entitled “To de Pe” (I am standing) by 22-year-old Cassio Luis Brito da Silva.

The youngster’s creations include photos of evenings of “Baile funk,” a musical style born in the favelas, and sculptures made with cigarettes. Da Silva, a favela resident himself, said being exposed to the work of other artists at the gallery serves as an inspiration.

“It is wonderful to see people like me exhibit in this place,” he says.

At Cinco Bocas, Weber encourages visits from disadvantaged youngsters from the favela.

Cintia Santos de Lima, 35, says her autistic son has benefited from the initiative.

“Before, he didn’t want to go out. It is good for us because in the community there are no places like these.”

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property