Whether you’re interested in the history of ceramics, the production process itself, creating your own pottery, shopping for ceramic vessels, or simply admiring beautiful handmade items, the Zhunan Snake Kiln (竹南蛇窯) in Jhunan Township (竹南), Miaoli County, is definitely worth a visit.

For centuries, kiln products were an integral part of daily life in Taiwan: bricks for walls, tiles for roofs, pottery for the kitchen, jugs for fermenting alcoholic drinks, as well as decorative elements on temples, all came from kilns, and Miaoli was a major hub for the production of these items.

The Zhunan Snake Kiln has a large area dedicated to presenting and preserving this heritage for the public. There is an information panel, with descriptions of the kilns in English, but a visit with a guide (Chinese only) is recommended for those who know they will have additional questions.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

AN ESSENTIAL TOOL

Several kilns, each with their own specialized purpose, can be seen here. The “steamed bun” or “turtle” kiln is dome-shaped, and was used to produce the red bricks, roof tiles and other elements of traditional courtyard (三合院, sanheyuan) homes that were once ubiquitous in Taiwan’s countryside. This kiln used wood or rice husks as its fuel and the firing process for a single batch of bricks could take several weeks.

By contrast, the black roof tiles used in Japanese-style architecture took only 15 hours to fire in a different kiln, fueled by coal. This kiln was given the moniker “dog-head kiln” by locals, for the coal feeding slot (the nose) and the two chimneys on top (the ears).

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Perhaps the most economically important kiln in the 20th century was the Hoffman Kiln, known locally as the Bamboo Steamer Kiln for its shape, or the Bagua Kiln in its larger iteration, which could produce bricks continuously without having to put out the fire between batches. This workhorse of the Taiwanese brick industry was by far the largest type of kiln, so the version on display here is only a miniature model, but it is the most photogenic of all. To see a full-sized version, visit the Zhongdu Tangrong Kiln in Kaohsiung.

The most culturally important type of kiln, however, might be the Cochin Kiln. This was a temporary kiln set up next to a temple while it was still under construction. With this kiln, an artist would create all of the relief decoration: the colorful animal and human figures that adorn the walls and roofs of temples, known as Cochin Ware. When the temple decoration was complete, the kiln would simply be disassembled and forgotten about. Zhunan Snake Kiln has preserved an example of such a kiln for posterity.

Also on display here are a large variety of jugs used for fermenting alcoholic products like rice wine. Producing these jugs used to be a major economic driver in Miaoli, with hundreds of manufacturers involved in the business. Each of these manufacturers had their own distinctive texture and stamp on the upper bodies of their jugs, and the Zhunan Snake Kiln has collected and identified a large sample of these to preserve this cultural heritage.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

REDEFINING THE LIMITS OF EARTH AND FIRE

The Snake Kiln itself was the first kiln on the property, built by founder Lin Tien-fu (林添福) in 1972 to run his business creating flower pots. The kiln is so named due to its long narrow shape, which stretches 20 meters in length. As plastic pots began to replace earthenware pots, Lin pivoted his business toward folk craft ceramics, education and research, but the snake kiln itself has remained in use to the present day. It currently fires ceramics just once a year, enough to keep it in good working order, with smaller kilns on site or electric kilns doing the majority of the firing the rest of the year.

Outside the snake kiln building is an area that is obviously an active workshop. Several smaller brick kilns stand here, with miscellaneous bowls, pots, tools and chairs arranged haphazardly throughout, along with stacks of firewood of various shapes and sizes. Among this chaos stands one rather unassuming brick kiln that looks much like the others, but holds the distinction of being the hottest wood-fired kiln on the planet.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

In 2016, Lin Rui-hua (林瑞華), son of the founder, achieved a temperature of 1563°C inside this kiln, as witnessed by a Guinness official. According to my guide, the secret to these high temperatures is not so much in the design of the kiln, but in the skill of the potter who is feeding the kiln. The selection of firewood is critical, as is the timing and method of feeding it into the kiln. With these temperatures, Lin Rui-hua has created an entirely new style of pottery, some of which is on display here.

Under extreme temperatures, trace elements in the clay begin to melt and fuse with components of airborne ash from the wooden fuel. The pottery ends up with a natural glaze with a wide range of colors and crystallized elements embedded within, and even the inside walls of the kiln end up coated in this bizarre, glossy, iridescent substance known as “kiln sweat.” Being able to control the visual appearance of the final products without damaging them in the intense heat is only possible thanks to Lin Rui-hua’s years of experimentation with clay and wood.

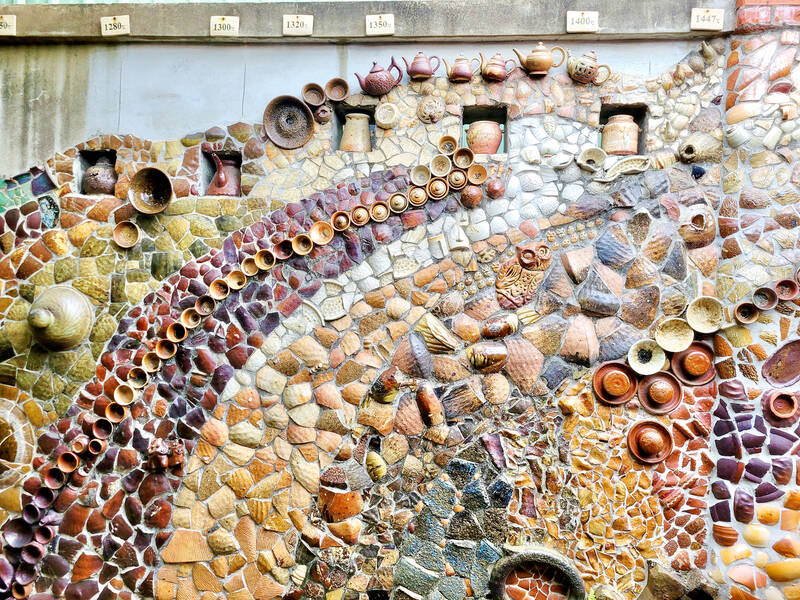

To better understand how firing temperature affects the final product, don’t miss the wall behind the workshop. At first glance, it appears to be nothing more than an artistic arrangement of pottery scraps. Upon closer inspection, however, you will see that each different band of scraps corresponds to a different firing temperature, which is labeled along the top. The texture, color and finish of the materials change drastically from one section to another.

In addition to Lin Rui-hua’s pottery, products made on site by other local artists are on display throughout the property, nearly all of which are available for purchase. On the second floor, there is a display of beautiful ceramic art created by the late founder of the kiln, Lin Tien-fu. Another room on the first floor exhibits a broader assortment of artisanal ceramics from artists all around the world, also available for purchase. The kiln occasionally hosts international artists who come to learn about the unique firing techniques used in Jhunan.

Getting There:

The kiln can be reached by a 20-minute walk from TRC Tanwen Station, or by catching Bus 5807, 5811, or 5803 from TRC Zhunan Station and getting off at the Kaiju Company stop.

Address: 7 Dapuding, Gongguang Village, Jhunan Township, Miaoli County (苗栗縣竹南鎮公館里七鄰大埔頂7號)

On the Net: www.skiln.com.tw

Classes: To book pottery classes visit linktr.ee/zhunansnakekiln and add the kiln’s LINE. There is an open house on the first day of every month: entrance costs only NT$50 but does not include a guided tour. For a guided tour on other days (NT$150), contact the kiln staff by LINE three days in advance.

Bonus: Children will receive a free gift when visiting on April 1, or on April 4–6, which have been designated as bonus open house days. Classes for making a pottery animal pen holder on April 1 and April 4 are also now open for registration.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades