In 1519, the German scholar Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa intervened to secure the release of a poor woman accused of witchcraft by a zealous inquisitor, who claimed that such women conceive children by demons.

“Is this how theology is done nowadays, using nonsense of this sort to put innocent little women to the rack?” Agrippa demanded.

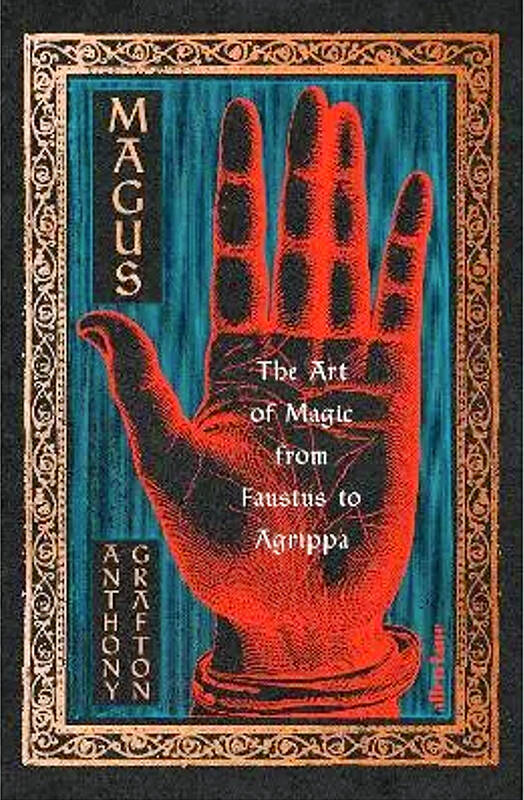

The incident is recounted in Magus: The Art of Magic from Faustus to Agrippa, Anthony Grafton’s dense and fascinating study of the evolution of magic through the 15th and 16th centuries, and it illustrates some of the contradictions and divisions that made the understanding and pursuit of hidden knowledge so fraught at the time.

Grafton, a professor of history and the humanities at Princeton University, shows that “magic” was a vast umbrella term encompassing everything from love philtres and homespun remedies involving the bones of toads, to proto-scientific disciplines such as cryptography, optics and engineering. When practiced by women and unlettered people (not to mention those of other faiths), it usually led to accusations of witchcraft, but articulated and published by learned men, it resulted in books that became the international bestsellers of their day.

Not that the learned men wholly escaped censure by the religious and civic authorities for their determination to test the boundaries of human knowledge. Agrippa — whom Grafton calls “the greatest magus of the 16th century” — had to fight to get his magisterial three-volume work On Occult Philosophy past the censors by appealing directly to the bishop of Cologne; although the book immediately went through three printings, it was widely banned and, according to Grafton, effectively ended its author’s writing career.

The Jesuit demonologist Martin Del Rio published a collection of tabloid-style anecdotes accusing Agrippa of practicing diabolic magic: “When he and Faustus travelled together, Del Rio claimed, they paid their bills in inns with coins that seemed genuine but turned into bits of horn after a few days.”

It examines the often uneasy, sometimes beneficial, three-way relationship between religion, magic and science

Faustus is, of course, the most infamous of the colorful characters who populate the pages of Magus — “a perfect star for this period show” — and Grafton attempts to separate the scant historical fact from the tangle of legends that surrounded him even in his lifetime.

Grafton tentatively identifies the original Faustus as Georg of Helmstadt, a schoolteacher dismissed from his post in 1507 on charges of sodomy, who reinvented himself as an itinerant magician and traveled around the Holy Roman empire building a reputation for supernatural powers so formidable that, on being expelled from the city of Ingolstadt, the council made him swear an oath not to take revenge.

But even at the time, opinion on the nature of Faustus’s powers was contentious. Some influential figures, including Martin Luther and his followers, attributed them to a diabolic pact (Luther claimed that Faustus called the devil “his brother-in-law”), while others, notably the Benedictine abbot Johannes Trithemius, who gets his own chapter later in the book, considered him a fraud — “a vagabond, a babbler and a rogue, who deserves to be thrashed.”

Through the principal magi of the high Renaissance, Grafton examines the often uneasy, sometimes beneficial, three-way relationship that existed between religion, magic and science. From outre self-publicists like Faustus to respected scholars such as the Florentine friends Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, who attempted to synthesize occult knowledge (including Jewish and Islamic learning) with Christian doctrine, he traces the expression of a desire for a comprehensive understanding of the cosmos and man’s place within it, as well as the drive to control the natural world, that paved the way for the evolution of scientific method.

“The magus,” he writes, “is a less respectable figure than the artist or the scientist… but he belongs in a dark corner of the same rich tapestry.”

Grafton’s inspiration for the book came from the work of the 20th-century scholar Frances Yates, who opened up the field of Renaissance occult philosophy, and while Magus is peppered with entertaining anecdotes, it is nonetheless a scholarly study that will most likely be more accessible to readers who already have some familiarity with the ideas of the period. It also feels as if it ends rather abruptly after the chapter on Agrippa; I would have been interested to read even a brief conclusion outlining the influence of the magus on later figures in the history of science. But these are quibbles; Magus is rich in detail and generously illustrated with examples of diagrams, ciphers and images.

In an age when the pace of new technological developments and our ability to harness forces beyond the human are giving rise to ethical questions and fears about the limits of knowledge, a long view of our relationship with magic could not be more timely. Because the concept of magic, Grafton writes, “played a crucial role in the rise of something larger than magic: a vision of humans as able to act upon and shape the natural world.”

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as