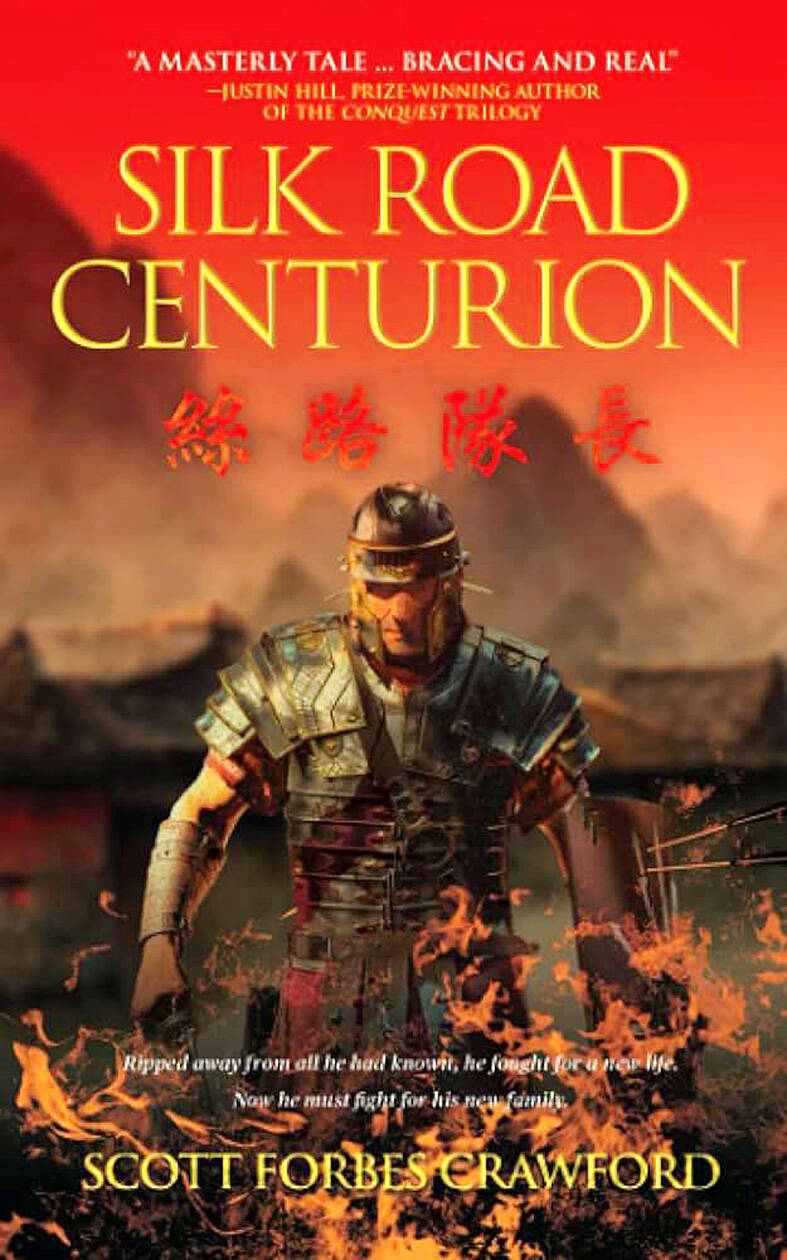

Novels about the ancient worlds of Greece and Rome are common enough. One thinks of Robert Graves (Claudius), Mary Renault (The Persian Boy) and, more recently, Harry Sidebottom (Warrior of Rome). Now we have a new one, Silk Road Centurian, set around 53-52BC on the ancient Silk Road that linked Rome with China.

Of course imaginative works on these topics go back even further. Shakespeare wrote seven plays on the ancient world, eight if you include A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But Chaucer was the real pioneer in English — his Troilus and Criseyde is his major long poem.

This novel concerns Marius Titinius from the Eighth Legion Gemina whose task was to guard and protect the Silk Road. But he is taken prisoner early in the book, and he is plunged into a world smelling of carpets, dyes, spices and incense as well as silk. His captors, plus other prisoners, include Parthians, Gauls, Germans, Greeks and members of a small Siberian ethnic group known as Kets.

Manius is powerless against such forces, even though he keeps hidden in a shoe a little figurine of the goddess Fortuna for luck. After the initial pitched battle Manius wakes to the sound of music. Is he on the banks of the River Styx, flowing down to Hades? No, but he is a prisoner along with 50 other Romans in what was a rare defeat for a Roman field army.

Among his captors was a boy called Rahmeg, truly formidable with a bow and arrow, but preferring when possible to play on his flute. Manius has the feeling that one day the boy will assist him in his escape.

Eventually they reach the Hyrcanian Ocean, now known as the Caspian. Here an escape fails and Manius is left with severed ligaments behind one knee. He is only able to crawl at first, though his condition improves after the ministrations of a female Chinese doctor, Kang. Other Chinese prisoners now join the group and both their features and their language astonish and perplex fellow prisoners and captors alike.

We learn in passing that Manius’s father, Faustus, had been a rich man but lost all his wealth and killed himself. Manius’s captors are led by a giant-like figure, Tangur, Rahmeg’s elder brother.

SHAMANS AND MUTILATION

This novel is reminiscent of the Warrior of Rome series by Harry Sidebottom, of which the fourth, Wolves of the North, was published by Michael Joseph in 2012. Crawford shares a considerable knowledge of Roman military habits, including some grotesque acts of mutilation.

Arriving at a Ket settlement the captives are quickly locked away again, only considered as living meat. Shamans, incidentally, feature prominently in this tale, as is only to be expected. And while captive Manius begins to learn scraps of Chinese speech.

Racial insults proliferate in this story, as perhaps is particularly common, Manius thinks, among nomadic people. Meanwhile, spring comes to these near-barren wastes.

This story is set at a time when Westerners were still ignorant of the origins of silk, in reality produced from the boiled carcasses of the silk worm after it has been feasting on mulberry leaves. Despite their ignorance of its origins, Romans were devoted to the diaphanous nature of silk in all its forms.

This book is not only the product of detailed historical knowledge, but is finely written as well.

“The fire hissed and popped as it drank the blood spray” is a typical sentence.

At one point Manius gets free and hobbles westwards with his Chinese comrades who believe their captors will expect them to run east, towards their distant homeland. Clutching his statuette of Fortuna, Manius soon turns east, however, with the Chinese once their captors are out of sight.

Earlier the Chinese doctor had explained the foundations of Chinese medicine, from qi onwards, at some length, showing perhaps Crawford’s desire to display his own knowledge of the subject. It’s fascinating nonetheless.

Crawford has lived in Asia, including Taipei, for over a decade and is apparently currently considering a move to Japan. Earnshaw Books is preparing to issue a new book of his, The Phoenix and the Firebird, written in conjunction with his wife Alexis Kossiakoff and described as a fantasy.

Another work of Crawford’s is The Han-Xiongnu War 133BC to AD89: The Struggle of China and the Steppe Empire Told Through its Key Figures (Pen and Sword Books).

To return to the question of earlier works on antiquity, it’s interesting to note that, Shakespeare and Chaucer apart, they mostly date from the 20th century. The 18th and 19th century are relatively short of such books. One very interesting exception is Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Last Days of Pompeii, published in 1834. Even more fascinating was the same author’s later work, The Coming Race (1871), in which a subterranean force known as Vril is postulated. Amusingly, this word was combined with Bov, from “bovine,” to make the name of the popular sandwich spread Bovril.

In a series of notes Crawford points out that at this period China was ruled by the Han Dynasty, which presided over many advances. Rome, meanwhile, was moving from a republican to an imperial government system and was already destined to extend its culture throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond. As for religion, the Chinese followed Taoism, the nomads an all-powerful sky god and the Romans the gods of ancient Greece, albeit in modified form.

The nomads, or pastoralists, were as a military force hard to beat. The Romans essentially fought on foot, concentrating on one-to-one combat, whereas the nomads fought from horseback with bow and arrow. This made them an unusual and formidable enemy for the Romans, with the “Parthian shot,” a shot backwards as they were retreating, a characteristic tactic.

This novel makes for compulsive reading. Crawford’s special interest may be China but he has mastered Roman life and habits as well. The plot of this novel allows him to combine the two, and incorporate pastoralism into the bargain. Beijing’s current Belt and Road initiative only adds to the interest.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an