Last Wednesday James Curran, the international editor of the Financial Review, asked “Does China really want to attack Australia?”

“The ‘China threat’ narrative is hardening into dogma,” he contended, implicitly conceding that fear of the capabilities and intentions of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has now become widespread in Australia. “But how likely is war with China,” he asks, “given Beijing’s steady need for growth — to ensure its internal stability and the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) control — and its hunger for Australia’s natural resources?”

Clearly deep observations, because as history teaches, no nation has ever gone to war in the Pacific over access to resources and aggressor states never need economic growth.

Photo: AP

After dazzling his readers with this brilliant opening, Curran then cites Jessica Chen Weiss (白潔曦), the longtime PRC supporter who has publicly argued that Taiwan should be annexed to the PRC, to support his claim that fear of the PRC is overwrought.

“China will clearly not disavow the use of violence, but mediation remains its preference,” he argues.

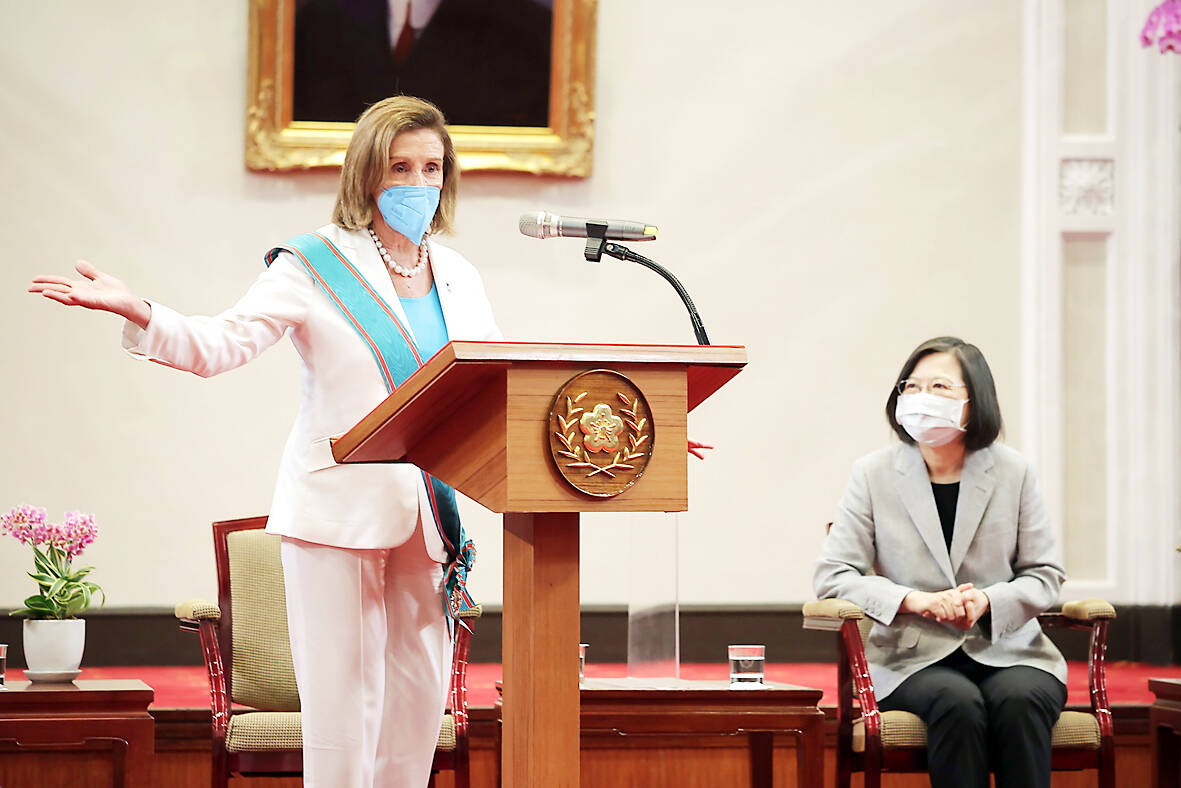

He then contends that “Beijing’s bellicose rhetoric and responses to provocations such as the visit by former US speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi to Taipei are designed expressly to avoid war.”

Photo: CNA

ZERO-SUM CLAIM

Well, in a way, that is true. They exist not to support the PRC’s desire to “mediate” as Curran claims, but to intimidate Taiwan and other nations into giving up without a fight. Mediation, after all, can only occur when there is some space on each side for concessions and some institutional arrangement for holding talks and enforcing outcomes. But PRC claims on Taiwan are zero-sum.

Curran’s idea of “mediation” is just a variation on the old pro-PRC theme of calling for a “process” between Taiwan and China without ever specifying what its goal is. Curran does not name it.

Photo: AP

Recall that the exercises held last month, which set a record for PRC aircraft sorties and involved large-scale naval activities in the Pacific, occurred without any “provocations” from Taiwan. These exercises demonstrated that just as many of us argued, PRC military exercises are not related to such events. Curran, naturally, ignores this.

Instead, he says that “... rather than presaging war,” the PRC’s aggressive intimidation of Taiwan “might be seen as helping to maintain the peace.” Unless, he adds, Taiwan elects an “extreme” president. Because, as always in the vocabulary of PRC apologetics, supporters of a free and independent Taiwan are “extreme,” whereas threats to maim and murder Taiwanese are … attempts to keep the peace. The real extremists reside in Beijing, preparing to plunge the region into war to annex an island that China has never owned and which doesn’t want Beijing’s rule.

CONFUSED TAIWANESE?

One reason that commentators like Curran avoid mentioning the end state of PRC-Taiwan “mediation” is that the Taiwanese themselves appear confused to outsiders.

A recent survey by Global Views noted that 31.9 percent of the population was in the “maintain status quo, then see” group, another 27.6 percent were in the “maintain status quo permanently” and 25.2 percent fell into the “support Taiwan independence” camp. Just 8.5 percent were for annexing Taiwan to the PRC. Such data are typically leveraged by commentators to imply that the Taiwanese don’t know what they want.

What do these numbers mean? An excellent paper from Chen Fang-yu (陳方隅), Austin Horng-en Wang (王宏恩) and Yeh Yao-Yuan (葉耀元), “The Multiverse of Taiwan’s Future: Reconsidering the Independence-Unification (Tondu) Attitudes,” takes a stab at explaining what is going on in voters’ heads. As they note, “Status quo has been the most popular option in Taiwan because, as prospect theory illustrates, people often choose the status quo during uncertain times, no matter what the ‘status quo’ is.”

Why are times “uncertain”? Because the threat of PRC violence suppresses rich public discussion of independence by its politicians and commentators and its many possible meanings in Taiwan. Discussions like Curran’s typically miss this point. If there were no threat of PRC violence, Taiwan would choose to be an independent and democratic state in a heartbeat.

Well, maybe not in a heartbeat — the debates would go on ad nauseum! But they would be public, and rich.

As Chen et al observe, many indicators show that the public opts for the status quo because it is the nearest thing to independence that Taiwanese can get. For example, a “thermometer” measurement that defines independence as soon as possible as 0 and unification as soon as possible as 10 was found to be 4.03 in a 2021 study. The public thus leans independence. The authors also note that support for changing the constitution is widespread, reaching nearly 30 percent even among the “annexation now” crowd (chock full of interesting and counterintuitive findings, the paper should be read in its entirety).

The paper also observes that surveys find that more than 70 percent of people agree that Taiwan is already a sovereign state with the official name of the Republic of China (ROC) and thus, there is no need for another declaration of independence, “a finding that has been stable across different waves of surveys in the past decade.”

MEDIA FAILURE

Yet, how many outside Taiwan are aware of this? The media failure is colossal. Instead, one hears talk in the international media of the threat of the never-defined but always dangerous “formal independence” when 70 percent of the population believes we are already (formally) independent and the problem for them is not independence but recognition.

This disconnect helps make believable the claim that politicians like Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) presidential candidate Willam Lai (賴清德), whose “independence” politics are dully mainstream and faithfully follow the DPP line, are somehow dangerous radicals.

The National Day celebrations last week highlighted how the DPP’s long-game strategy of steadily hollowing out symbols of the ROC has worked. The ruling party referred to it as the “Taiwan National Day” celebrations, causing ROC diehard and former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) to skip the proceedings, a tribute to the success of the DPP’s long game.

The ROC diehards like Ma once hoped to subsume Taiwan into their version of China. Instead, the opposite has happened: Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) insistence on the ROC name, leveraged by the DPP in its constant reiteration of its policy that “we are already independent as the ROC,” has lead the population to identify Taiwan as the ROC, instead of China, and feel it is already independent.

If only the DPP could work that magic on the PRC.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) and the New Taipei City Government in May last year agreed to allow the activation of a spent fuel storage facility for the Jinshan Nuclear Power Plant in Shihmen District (石門). The deal ended eleven years of legal wrangling. According to the Taipower announcement, the city government engaged in repeated delays, failing to approve water and soil conservation plans. Taipower said at the time that plans for another dry storage facility for the Guosheng Nuclear Power Plant in New Taipei City’s Wanli District (萬里) remained stuck in legal limbo. Later that year an agreement was reached

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.

In a high-rise office building in Taipei’s government district, the primary agency for maintaining links to Thailand’s 108 Yunnan villages — which are home to a population of around 200,000 descendants of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies stranded in Thailand following the Chinese Civil War — is the Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC). Established in China in 1926, the OCAC was born of a mandate to support Chinese education, culture and economic development in far flung Chinese diaspora communities, which, especially in southeast Asia, had underwritten the military insurgencies against the Qing Dynasty that led to the founding of