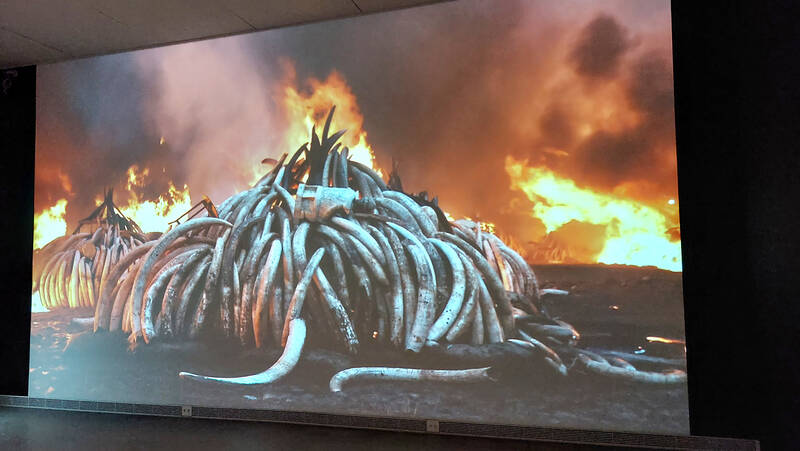

Huge piles of elephant tusks and rhino horns confiscated from poachers go up in flames as smoke blacks out the sky. The scene, part of a video played on a giant screen in a dark room, is an installation from the “Anthropocene” exhibition at the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts.

Most other pieces at the exhibition are similarly super-sized and awe-inspiring. The smallest photo prints are almost as tall as an average person — a likely attempt by photographer Edward Burtynsky and documentary directors Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier to underline the immensity of their subject matter: to document the geographical and ecological changes wrought upon our planet by human beings.

Burtynsky’s photographs anchor the exhibition occupying three halls. Visitors to the first hall are greeted by a 6-meter wide print of a marble quarry in Italy showing an excavator working in front of a sheer rock face shaved off in neat, straight lines. The image is flanked by a smaller picture of an outcrop from Spain displaying dozens of rocky strata layered on top of each other in a wavy pattern, underlining the contrast between the natural and the human-made.

Photo: Doruk Sargin

Imagery that has become the staples of environmentally-conscious exhibitions — people standing in landfills, garbage-strewn rivers and polluted waterways — are sparse in “Anthropocene,” as it seeks to depict the human state as is, without judgement. And so visitors are treated to aerial photographs of a highway cutting through a suburban neighborhood in California, a busy intersection in Lagos and phosphate production plants in Florida. Added to these are images of perfectly rectangular lithium mines from Chile, where booming demand for electric car batteries is transforming the Atacama Desert, which, normally, should be devoid of human life. In the second hall, however, the line between the natural and the human-made becomes blurred as what appears to be a close-up photograph of an ammonite is revealed to be an aerial image of a potash mine in Russia.

The artists have also made a distinction between “good Anthropocene “ and “bad Anthropocene.” An example of the former is displayed in a video called Danger Trees by Baichwal and De Pencier, showing trees that pose a danger to humans or the environment in Vancouver being exploded in controlled detonations to bring them down. The trees are then left on the forest floor to decompose naturally. The artists argue that this quickens the natural pace of the decomposition process, and causes no harm to the environment.

The exhibition also takes a different approach to the problem of coral bleaching. Instead of filming or photographing destroyed corals, Baichwal and De Pencier collected coral samples, placed them in an enclosure mimicking their natural habitat and subjected them to the stresses caused by climate change. The result is a striking time-lapse video showing vibrant corals fading away as symbiotic algae crucial to the corals is wiped out.

Photo: Doruk Sargin

The adjoining room houses the video installation showing the burning tusks and rhino horns. The scene is from 2016, when the Kenyan government set on fire hundreds of tusks and horns it confiscated over the decades, to send the world the message that the illegal trade had come to an end. However, the effort was too little, too late, as the last male northern white rhinoceros died in 2018, leaving behind only two females of its kind.

Despite its somber subject matter, “Anthropocene” is a refreshing break from similar works, free from pretense and finger-pointing. Rather than burdening the visitors with a sense of guilt, the exhibition imbues a sense of awe and wonder for the great changes humanity has brought about simply by existing. As Baichwal declares, its goal is “to not preach, harangue or blame, but to witness, and in that witnessing, try to shift consciousness.”

Photo: Doruk Sargin

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,