May 5 to May 11

What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint.

The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with principal Kokuro (also known as Kojin) Shimomura personally moving into the dorms to monitor them.

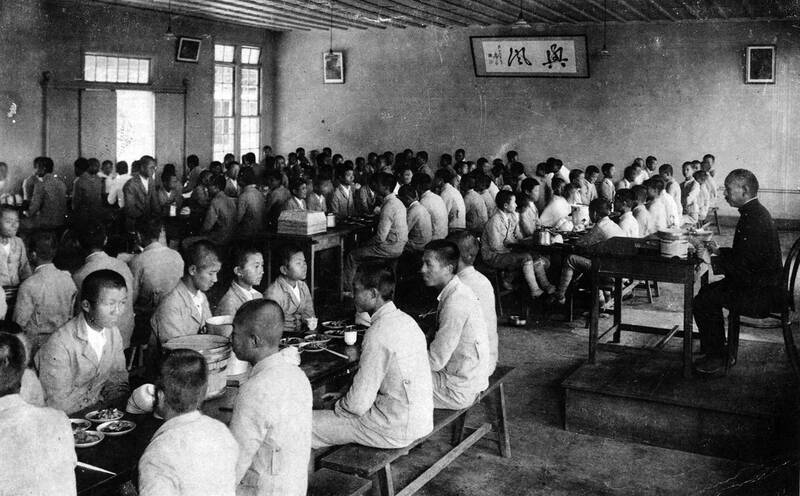

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

This high-handed approach sparked further unrest, and the authorities at one point called in the military police to surround the campus while they negotiated with the parents. The students then went on strike, and by May 16, only two-thirds of the student body — which was 97 percent Taiwanese — showed up to class.

Still refusing to back down, the incident ended with Shimomura expelling 36 students, while more than a dozen quit.

This might have just been a minor incident, but it was a reflection of the tension between Taiwanese and the Japanese colonizers. The political and cultural resistance movement was reaching its peak, with Taiwanese intellectuals pushing for local autonomy while encouraging ethnic and cultural consciousness.

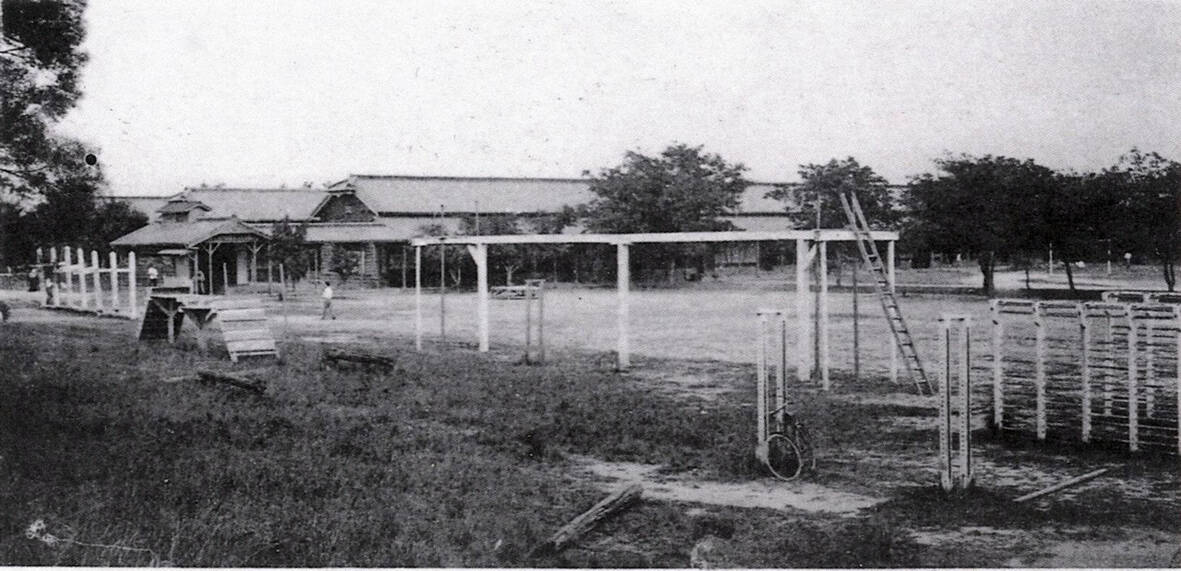

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Often looked down upon by their Japanese counterparts, the students reacted strongly against the discrimination and fought back. Several other student strikes took place during the 1920s, but this was the most significant.

RACIAL DIVIDE

As detailed in last week’s feature, the establishment of Taichung First High School in 1915 was a push for equality, as it was the first secondary institute in the colony to accept Taiwanese students.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

The three high schools in Taiwan remained racially segregated with different systems and curricula until the 1922 Taiwan Education Act overhauled the education system as part of the colonial government’s plan to assimilate Taiwanese into patriotic Japanese citizens.

Five more high schools were set up across Taiwan that year, and all schools were required to accept both Taiwanese and Japanese students. However, if a city had two high schools, the student body at one was always predominantly Japanese while the other was Taiwanese.

In 1927, for example, Taichung First High School was 97.1 percent Taiwanese, while Taichung Second High School was 93.2 percent Japanese. By contrast, Kaohsiung High School was 33.6 percent Taiwanese and 66.2 percent Japanese.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Japanese who attended Taichung First were generally those who couldn’t make it into Taichung Second. There were exceptions, as Chu Pei-chi (朱珮琪) details in The Cradle for Taiwanese Elites: Taichung First High School (台籍菁英的搖籃: 台中一中). One student surnamed Machida enrolled in Taichung First because his father believed that to thrive in Taiwan, the boy had to make Taiwanese friends.

A TALE OF TWO PRINCIPALS

Taichung First High School’s first two Japanese principals, Shinichi Tagawa and Hideo Azukisawa, were beloved figures who reportedly cared for the students and did not discriminate against them.

When emperor Hirohito visited Taiwan in 1923, Second High insisted that he visit them first because they primarily served Japanese students. Azukisawa was furious, insisting ethnicity should not be a deciding factor, and engaged in a heated public argument with Second High’s principal. He prevailed, earning him much respect from the Taiwanese students.

Hsieh Tung-min (謝東閔), who attended the school until 1925 and was later the first vice president under Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), says that the students had already attempted a strike under Azukisawa’s tenure. The students had arranged to stay at a hotel in Keelung for their graduation trip, but discovered that the place was under renovation and did not have enough rooms. The Japanese teacher allegedly said that it didn’t matter since the students were Taiwanese chankoro, a highly derogatory term.

The furious students trashed the hotel, fought with their Japanese classmates and refused to attend school until finally Azukisawa asked them to calm down and scolded the teacher. Such reactions by Taiwanese students to discrimination were not uncommon, as Chu cites several other incidents in her book.

Shimomura, who arrived in 1925, was much stricter than Azukisawa. For example, he forbade students from speaking in Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese) on campus and required them to speak in proper, standard Japanese, writes Chang Chi-lin (張季琳) in “Showdown between Chang Shen-chieh and Kojin Shimomura: The student strikes at Taichung First High School” (張深切和下村湖人的對決: 以臺中—中罷課事件為主). Additionally, he spoke Japanese with a heavy Kyushu accent, leading to discontent among the students.

Chang writes that Shimomura was a capable educator who tried to be fair, but the students didn’t like him. After the strikes, he was almost universally reviled and soon quit.

RECOUNTING THE INCIDENT

Taiwan Minpao (台灣民報) detailed the events in “The truth behind the Taichung First High School’s student strikes,” in its May 29, 1927 edition. It stated that the wife of the head cook was allowed to move into the school under the condition that she work for her meals, eat after the students and move out if she came into conflict with them. Not only did she not follow the rules, she brought her children with her. The noise led to numerous disputes with those students living on campus.

After the rat feces incident, the students complained to the Japanese dorm supervisors, who were dismissive and accused the students of causing trouble. In response, the fifth-year Taiwanese resident advisor quit in protest.

Upon hearing this, Shimomura abolished the dorm’s self-management system and declared that orders from dorm supervisors’ were absolute. On May 6, Shimomura gathered the students, reiterating that he would neither fire Nakamura nor expel his wife, and those who continued to press the issue would be punished. The next day, he personally moved into the dorms, prompting the students to set off firecrackers indoors at night.

The police then rounded up the students’ parents and asked them to bring their boys home, but no compromise was reached. On May 12, Shimomura asked all fifth-year students to leave the dorms or face forceful removal by police. The second, third and fourth year students followed voluntarily in protest. The alumni association and other civic groups tried to step in and negotiate for the students, but to no avail.

One of the negotiators was Chang Shen-chieh (張深切), an anti-colonial revolutionary who later admitted to helping direct the strikes. He was arrested for his role and acquitted, but jailed on other charges.

The first expulsions came down on May 23, involving 10 students. Many students returned to school on June 1, but some teachers displayed a poor attitude towards them, believing they shouldn’t be allowed back. This led to another wave of strikes — particularly against teachers who often discriminated against Taiwanese. On June 13 and 14, the school handed down more expulsions, drawing the incident to a close.

Taiwan Minpao printed numerous articles condemning the school’s actions, but Shimomura stuck by his decision.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan