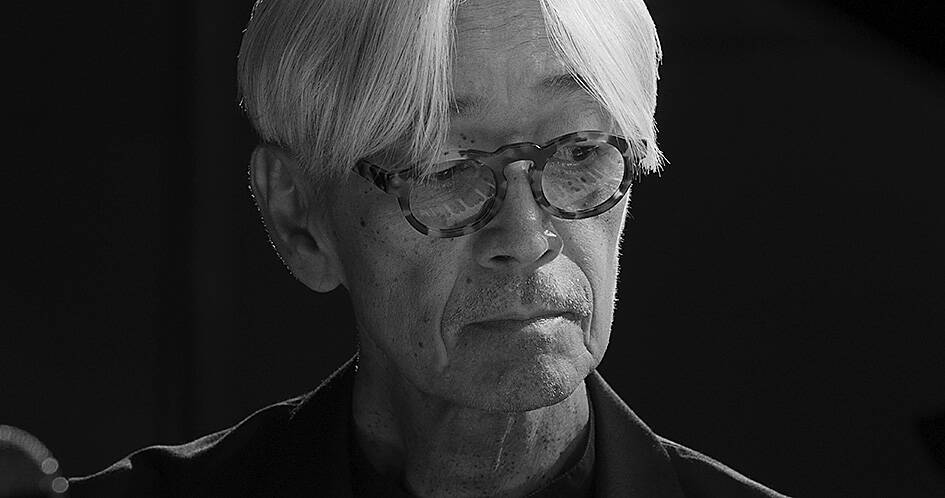

Sitting alone before a grand piano in a stark studio, Ryuichi Sakamoto takes the listener on a journey of his life, playing 20 of his compositions.

Shot entirely in black and white, on three 4K cameras, the film Opus, directed by Neo Sora, is the Japanese composer’s farewell, poetic yet bold, and deeply heartfelt.

Its world premiere is set for the Venice International Film Festival this month. The filming took place over several days, just a half year before his death on March 28 at 71.

Photo: AP

Sakamoto had been battling cancer since 2014, and could no longer do concert performances, and so he turned to film.

He plays pieces he had never performed on solo piano. He delivers a striking, new slow-tempo arrangement of Tong Poo, a composition from his early days with techno-pop Yellow Magic Orchestra that catapulted him to stardom in the late 1970s when Asian musicians still tended to be marginal in the West.

“I felt utterly hollow afterward, and my condition worsened for about a month,” Sakamoto says in a statement.

Photo: AP

He speaks only a few lines in the film.

“I need a break. This is tough. I’m pushing myself,” he says barely audibly in Japanese, about midway through the film.

He also says, “let’s go again,” indicating he wants to play a sequence again.

For the rest of the nearly two-hour film, he lets his piano do the talking.

The notes resonate from his fingers, lovingly shot in closeups, sometimes slowly, one pensive note at a time. Other times, they come jamming in those majestically Asian-evocative chords that have defined his sound.

After each piece, he lifts his hands up from the keys and holds them there in the air.

Opus is a testament to Sakamoto’s legendary filmography. He composed for some of the world’s greatest auteurs, including Bernardo Bertolucci, Brian DePalma, Takashi Miike, Alejandro Inarritu, Peter Kominsky and Nagisa Oshima.

The film is also evidence he remained active until the very end. He performs an excerpt from his meditative final album 12, released earlier this year.

By the time Sakamoto starts playing the melody from Bertolucci’s 1987 The Last Emperor, the emotions are almost overwhelming. The soundtrack, which also included musician David Byrne, won both an Oscar and a Grammy.

Sora, the director, who was raised in New York and Tokyo, says he and the crew were determined to capture the sense of time and timelessness, so crucial in Sakamoto’s art, in what everyone knew might be his final performance.

All the sounds that usually get taken out in post-production, rustling clothing, clicking nails or Sakamoto’s breathing, were purposely kept, not minimized in the mix.

“Part of the reason why we decided to shoot in black and white was because we thought that also highlighted the physicality of his body, with the black and white keys of the piano,” said Sora, named one of the 25 New Faces of Independent Film by Filmmaker Magazine in 2020.

Sakamoto first came up with a set list, and the filmmakers worked out with him in advance a detailed plan for a visual narrative and concept.

Designed as a film from the get-go, not just a documentary of a performance, the work features the lighting design, artful long takes and Zoom-lens closeups concocted by Bill Kirstein, the director of photography.

“We were able to get shots of hands and keys that we were never able to get before,” said Kirstein, comparing the film’s imagery to a drawing.

Hundreds of pounds of weights were laid on the floor so the camera dolly could move silently without creaking.

A memorable moment comes toward the end when Sakamoto plays Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, from the 1983 Oshima film bearing the same title and starring David Bowie and Golden Lion-winner Takeshi Kitano.

Sakamoto also acted in the film, portraying a World War II Japanese soldier who commands a prisoner-of-war camp. He was young, barely in his 30s. Yet in so many ways he remained unchanged as that frail silver-haired bespectacled man, crouched over his piano.

As the film moves to the final tune, Sakamoto has disappeared, gone to that other world that some call heaven. The piano, under a spotlight, is playing on its own, a reminder his music is eternal, and still here.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the

Six weeks before I embarked on a research mission in Kyoto, I was sitting alone at a bar counter in Melbourne. Next to me, a woman was bragging loudly to a friend: She, too, was heading to Kyoto, I quickly discerned. Except her trip was in four months. And she’d just pulled an all-nighter booking restaurant reservations. As I snooped on the conversation, I broke out in a sweat, panicking because I’d yet to secure a single table. Then I remembered: Eating well in Japan is absolutely not something to lose sleep over. It’s true that the best-known institutions book up faster

Though the total area of Penghu isn’t that large, exploring all of it — including its numerous outlying islands — could easily take a couple of weeks. The most remote township accessible by road from Magong City (馬公市) is Siyu (西嶼鄉), and this place alone deserves at least two days to fully appreciate. Whether it’s beaches, architecture, museums, snacks, sunrises or sunsets that attract you, Siyu has something for everyone. Though only 5km from Magong by sea, no ferry service currently exists and it must be reached by a long circuitous route around the main island of Penghu, with the