July 3 to July 9

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) seemed to be foreshadowing his tragic fate when he said, “I make people laugh everyday, but all I have is pain and sadness,” in the 1980 box office hit, The Clown (小丑).

Director Chu Yen-ping (朱延平) says he only cast Hsu as the titular clown who had fallen on hard times because his preferred actors requested too much money. “Hsu Pu-liao” sounded like “endless hardship” in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), how could someone with such a name make people laugh? Chu wondered at first.

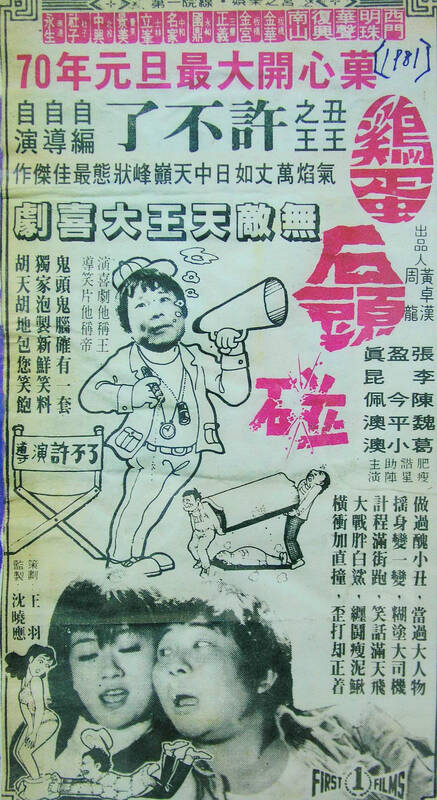

Photo courtesy of Hsinchu City Cultural Affairs Bureau

However, the entertainer was a natural at the role, bringing to life the spirit of those at the bottom rungs of society with a mixture of self-deprecation, exaggeration, magic tricks and other special techniques he learned growing up in a circus troupe. Chu recalls years later, “Hsu was the one who taught me the true essence of comedy.”

The movie made Hsu Taiwan’s most sought-after comedian, but it was also the beginning of his nightmare. Kind-hearted and gullible, he was forced by gangsters to make film after film, traveling to as many as three sets per day and given morphine to stay awake. Hsu became addicted to the drug, drank heavily and overspent to numb his pain, reportedly running away from sets several times. But his movies continued to do well, and few knew about his plight.

By 1985, after starring in an astonishing 64 films in just six years, Hsu’s body was completely ruined. He died from alcoholic hepatitis complications on July 3, 1985, at just 34 years of age. His final film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝), which he reportedly filmed through severe pain, premiered the next day.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

MAGICIAN’S SON

Hsu did not have a happy childhood, and Chu recalls that every time he spoke about it the story seemed different. Some reports say he was born in 1951 to a destitute family in Hsinchu (新竹) and given to a magician at a young age, but others maintain that the magician was his biological father.

Known then as Yeh Tie-hsiung (葉鐵雄), Hsu went through rigorous and abusive training as a child, learning magic tricks, ventriloquy, voice effects and circus techniques such as swallowing ping pong balls and riding a unicycle. His father, or stepfather, regularly beat him and threw chairs at him whenever he didn’t perform well.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Film Festival

Hsu was sent to Hsinchu City at the age of six to attend elementary school, and after one semester he took the chance to run away. The child eked out a living by picking up cigarette butts and collecting the remaining tobacco inside to sell, and also did other odd jobs such as shining shoes and pulling rickshaws. He was eventually found by his father and severely punished.

This scenario would repeat over and over again until the death of Hsu’s mother when he was 11 or 12 years old. At that point, he had decided to take the entertaining business seriously and trained hard in his father’s troupe. Hsu never went back to school after that first semester, and he reportedly could not read the movie scripts, relying on memory and improvisation.

Although Hsu often played bumbling characters who found no luck in romance, he actually had quite a colorful love life, fathering his first child, Chou Ming-tseng (周明增), at the age of 18 with a dancer in the group. His father vehemently opposed the relationship and chased the dancer away, and Hsu never met the child until years later. Chou looked exactly like his father and also became an actor.

Photo: Chen Yi-shan, Taipei Times

SELF-DEPRECATING STAR

Hsu became quite a successful traveling performer, and his big break came in 1977 when he took part in a trip to entertain troops stationed on offshore islands. His unique act caught the attention of China Television Co (中視), who recruited him as a regular actor.

Hsu played a supporting character named Hsu Pu-liao in the 1977 drama series Leifeng Pagoda (雷峰塔). His performance was a national sensation and garnered more attention than the protagonists, and he took on the character’s name as his stage name.

A year later, Hsu hosted the variety show A Rainbow (一道彩虹) with popular singer Fong Fei-fei (鳳飛飛). This is where he was able to integrate all his skills into an appealing act, especially in a segment where he plays a clumsy magician who keeps accidentally revealing his tricks.

In 1979, the Ministry of National Defense was recruiting actors to star in On Chenggong Ling (成功嶺上), which depicted the lives of young army recruits. Hsu was not a major character, but again his exaggerated, comical performance played a significant part in the movie’s success.

Hsu was suspended from the television station for missing too much time for the movie, but it didn’t matter as he already had a new career as a film star. At a time when most comedies featured handsome, charismatic leads, Hsu was the first actor to mostly play disadvantaged, tragicomic roles that capitalized on his misfortunes. He had the uncanny ability to make people laugh at his suffering without making them feel bad about it, critics said.

WORKED TO DEATH

As one of the highest paid actors in the nation, Hsu became entangled with the mafia, who practically forced him to work non-stop. In addition to the backbreaking filming schedule, he also had to host live variety shows. Since Hsu was able to hold the stage by himself — even playing all the instruments — it was much more efficient to hire him than other stars who required a large support cast.

According to a Formosa TV (民視) Taiwan History program, the ruthless gangsters weren’t just content with making Hsu work, they also pressured him to gamble away his earnings in their parlors.

As he did as a child, Hsu ran away. The history program says he was once found camping on a beach in Keelung after going missing from a film set for 20 days. He eventually turned to alcohol and shopping sprees to cope with the stress and unhappiness. At the same time, Hsu maintained his generosity, donating money to orphanages, fire victims and other needy people.

Hsu’s morphine addiction grew worse over the years to the point where he would visit different clinics to receive painkiller shots that contained the drug. It’s said that sometimes he got more than 100 shots per month, and his arms and legs showed severe needle damage that had to be covered while filming.

He discovered he had cirrhosis and all sorts of health problems by 1984, but he continued to work tirelessly until his death.

In his final film, Hsu’s clown character walks around with a ventriloquist puppet, who serves as an alter ego to say what he couldn’t say. They say art imitates life, but it especially rings true for Hsu.

He explains in one scene, “My whole life, I’ve listened to others and did whatever they told me to. No matter who it was, I let them hit me, scold me and kick me. So I wanted to create another me.”

The puppet then says, “I don’t want to go on stage today, I just want to sleep! I want to be a protagonist, not a puppet!”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)