The 1980s were a golden age of travel in Asia. Most of the region’s guide books were only in their first editions, and the dots were still being connected on a banana pancake trail of cruisy guest houses, hippie cafes and improvised transport.

Describing those years, the travel writer Pico Iyer declared backpackers “the cool invaders,” and “a tribe of counterculture imperialists” who paved the way for a new wave of tourism-fueled globalism. These Western pilgrims, he found, were largely “refugees from affluence, voluntary dropouts from the Promised Land.” And they lived by an unofficial code: “Thou shalt not plan. Thou shalt not hurry. Thou shalt not travel without backpacks, on anything other than back roads. And thou shalt not, ever, in any circumstance, call thyself a tourist.”

Iyer may have been one of the most prescient observers of that traveler generation, but now a new book by Taipei-based photojournalist Chris Stowers returns to the raw, lived feel of those glorious days of falling off the map in Asia.

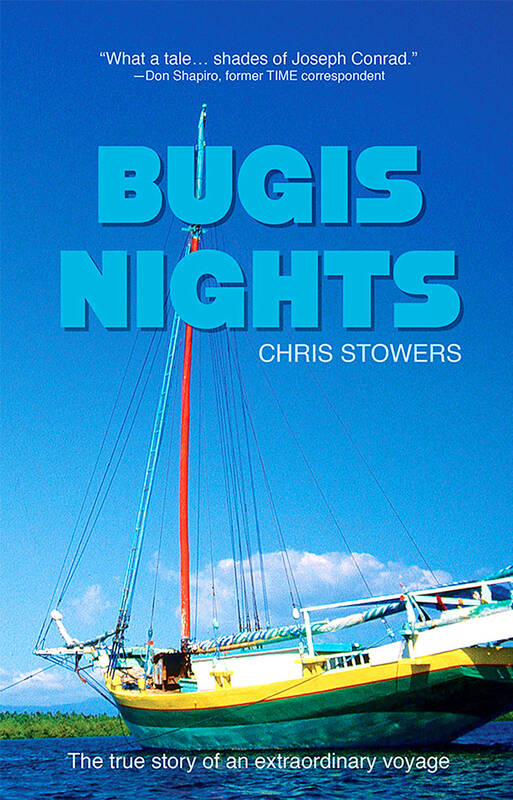

Stowers’ Bugis Nights, which charts both a 2,000-kilometer voyage across the Java Sea in a 19th-century-design teak sailing ship and an overland trek across the barren Tibetan Plateau, reads like the mother of all backpackers’ tall tales. Though it is a non-fiction chronicle — technically speaking, it is a memoir from 1987 and 1988 — the story races ahead like a high-octane road novel. One can easily imagine hearing these stories over cheap bottled beers and smuggled hashish in some out-of-the-way hostel and finding them almost too much to believe, but only in the way that one person’s adventure becomes transposed as another’s fantasy.

Stowers’ voyaging, which begins with the author seeking to escape the bleak prospects of dreary, conformist London for a new life, also takes the form of a bildungsroman for the 1980s-generation wandering soul. As he embarks on a winding pilgrimage to personhood, it is only through this journey that he finally stumbles into his true calling — a career as a photojournalist.

The action of Bugis Nights centers around an oceanic voyage through the Java Sea. Falling in with a ragtag crew of adventuring Western travelers, Stowers embarks from eastern Indonesia to Singapore in “a beautiful, seventy-foot long traditional Bugis perahu, typical of the sloops used for centuries to trade.”

Such ships were once known as Makassar traders in colonial Singapore, but this vessel was actually produced by another south Sulawesi race of ocean traders and pirates, the Bugis. Pronounced “boogey,” they are the namesake of both the nightmarish “bogeyman” of mariners’ tales and Singapore’s “Bugis Street,” a former mercantile hub that is now a quayside bar zone.

Stowers chances into the journey via the kind of encounters one can only have when one is twenty-something and winging it. In an East Timur guesthouse, he encounters a group of young Frenchmen looking to buy a traditional vessel and sail her all the way to France in time for the 210th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. The ship they find is called the Kurnia Ilahi, a sloop built exclusively of wood — there is not a single nail, bolt or other scrap of metal in her construction.

Events unfold rapidly. There is a large cash transaction in a dark paradise called Jampea, a tropical island with no telephones and governed by a brooding strongman, the deal mediated by a conniving local broker working a squeeze on both ends.

Stowers, who professes “true adventure can only be had by stepping into the unknown alone,” slides down the slippery slope from curiosity of the French venture to hitching a ride to the next island to “What the hell am I doing here in the middle of the Java Sea!” He understands full well that the journey may be insane, but despite his wry recognition of every progressive misstep, the siren song of raw adventure is too much for him to resist.

The crew of seven Western sailors is headed by megalomaniac captain Pascal, below whom the rest organize into their own Lord-of-the-Flies type pecking order. It is on Pascal’s assurances that they set off on the high seas criminally unprepared — without a ship-to-shore radio, life vests, distress flares or modern navigation equipment. Their only means of plotting a course is a compass nailed to the mast, a sextant Pascal doesn’t really know how to use, and a standard map of Southeast Asia that Stowers fishes out of his backpack.

Stowers account marvelously captures the raw sensations of the voyage — the taste of oversweet coffee in a fisherman’s shack, the nostril burn of clove cigarettes, the phosphorescent glow of plankton in cool water rushing beneath your fingertips — so much so that it’s almost impossible not to get swept along, even as the mainsail crashes into the sea and very real fears of death loom in the form of a squall on the horizon.

Though Stowers had not even contemplated professional photographer before this sea voyage, within little more than a year following the journey, he’d shot his first of many covers for the news magazine Asiaweek –– a portrait of Malaysian politician Nik Aziz –– and would go on to contribute to most major periodicals of the day, including Time, Newsweek, The Economist, Le Monde and the New York Times.

Currently, Stowers shoots for the London-based Panos photo agency, for whom he’s documented the migration of Syrian refugees across Europe, Russia’s 2008 attacks on Georgia, the 2005 Pakistan earthquake and the 2004 south Asian tsunami. He has also published a fantastic photobook, Hair India: A Guide to the Bizarre Beards and Magnificent Moustaches of Hindustan.

Stowers’ first visit to Taiwan came in 1991, just three years after his Java Sea adventure, when he sailed into Kaohsiung Harbor on a ferry from Macau. That year, he photographed the protests of the Wild Lily Movement — “People thought it might turn into another Tienanmen,” he once said — and assignments kept him returning to Taiwan regularly from his base in Hong Kong.

In 1996, covering Taiwan’s first direct presidential elections, Stowers’ photo of a billboard of Taiwan’s president Lee Teng-hui dressed as Superman landed on the front page of the UK’s Guardian newspaper. Not long after, he moved to Taipei, which he has used as a base for his photojournalism ever since.

In all Stowers’ years on the road, he kept detailed diaries, and Bugis Nights is his first attempt to bring these stories to a wider public. If the prose is at times a bit rough, the storytelling is always taut, and the action never fails to move propulsively forward. The book’s greatest virtue is how, in a freeze-frame portrait of a magical era, it captures the exuberance of youth and the raw sensations of travel. It is most definitely a page turner. Though I will not spoil the ending, I can tell you this much––as befitting of any tall backpacker’s tale, it is a kicker!

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only